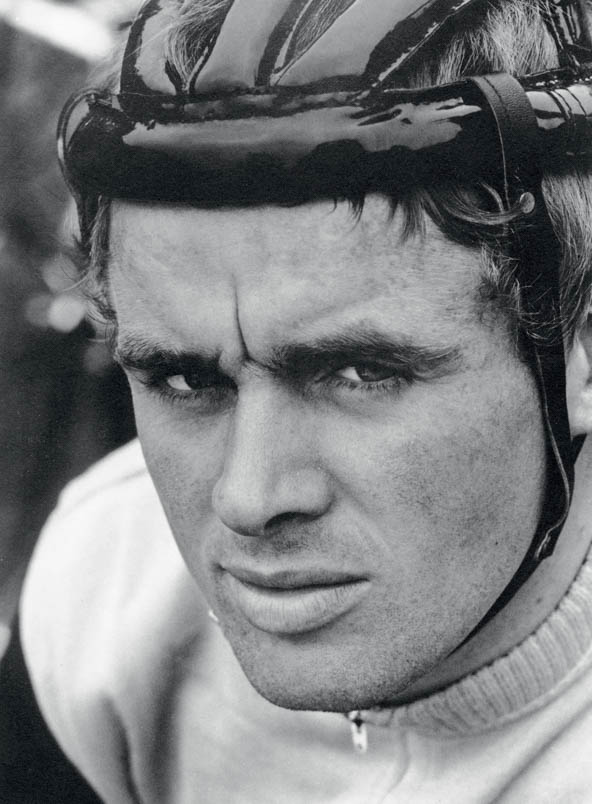

An incredible determination

Meanwhile, Hennie punishes his body day in and day out. Already in the early stages of his love for cycling, he shows an incredible determination. He decides to participate in the ‘wild’ Tour of Wierden with four friends. How do they get there? By bike, of course. When the day arrives, the rain is pouring down. None of his friends feel like riding all those kilometers to Wierden in this bad weather. But Hennie, who has no idea how to get to that place, gets on his bike. A promise is a promise, and he pedals towards Almelo in the pouring rain. Rain is not a reason to stay home. Along the way, he stops once to wring out his soaking wet clothes. When he finally arrives at the course, the participants are already lined up for the start. Too late, judges the organization, but they didn’t count on Hennie. He has actually cycled all the way from Denekamp. ‘In the rain no less,’ he adds redundantly. Alright then, he can start, but first he needs to get a race number. Hennie suspects a trick, thinks that the riders will be off while he’s still busy getting his number and leaves without one.

Hennie turns out to be a talent. He belongs to the leading group of four and only lets one rider pass him in the final sprint. He can choose between a small trophy or a real cycling jersey at the prize table. The temptation is strong to exchange his football shirt with cut-off sleeves for a real cycling jersey, but he chooses the trophy, the first of many to come. The fact that he has to ride back home in the pouring rain with his trophy afterwards barely bothers him. Mile after mile, he covers the distance, first to Almelo and then over the soaked roads that endless stretch back to Denekamp and Noord Deurningen. It’s already dark when he arrives at the farm on Schotbroekweg, proud and overjoyed with his trophy. He is just as proud of it as he will later be of his Olympic medal.

Briefing

He goes from one wild race to another and consistently wins prizes. The highlight for ‘boys with racing ambitions’ is undoubtedly the Tour de Junior in Achterveld, a creation of Jan Schouten, who finds host families in the village and surrounding area willing to provide accommodation for the budding young cyclists for a small week. In 1964, at the age of 15, Hennie also applies for a spot in the lineup but is rejected because the starting list is already full. He is inconsolable and then writes a touching plea to organizer Schouten.

“Gentlemen. Recently I received notice that I cannot participate in the Tour de Junior, as I am now on a waiting list. I would like to ask if there is still a possibility to participate. Because I have trained a lot and even more now that the doctor’s certificate has also been sent. With this, I conclude, hoping to still be able to participate and to receive a response from you.”

The organizer has a change of heart: Hennie is allowed to participate. His first Tour de Junior is rather anonymous, but when he returns a year later, the little Tukker becomes the main protagonist of the race. He is the great attacker, the man of constant attacks, which ultimately results in the qualification of ‘most combative rider.’ This will later become his trademark among the professionals.

At home, there was initially skepticism about Hennie’s cycling ambitions. Each of the six sons and the daughter can choose the sport they want, but cycling… that is quite far outside the family’s field of vision. They let him go ahead anyway, also seeing the unbridled enthusiasm with which Hennie throws himself into cycling.

A year after the second Achterveld adventure, things get more serious. Hennie receives an official racing license from the Royal Dutch Cycling Union. As a novice, he and his teammates sometimes pedal dozens of kilometers to get to a race, compete, and then cover those same dozens of kilometers back home afterwards. Sometimes the course is so far from Twente that Hennie asks for ‘lodging’ with riders who have transportation, like contractor Meijer, whose son Theo is also a strong rider. The bikes are secured with toe clip straps on a rack mounted on the car roof. There are other riders with whom he occasionally gets to ride along.

The setup on the car roof doesn’t always hold up, as Hennie and his fellow passengers find out when they return home after a training race in Ekehaar near Assen in early spring. A leg of the rack on the car breaks off. Slushy wet snow on the windshield, interspersed with icy rain. But Hennie and his buddies Theo Meijer, Ben Wolkotte, Johan Pegge, and Marinus Ekkelboom have to get home. So they decide to roll down the rear window and take turns holding the rack in place with an arm outside the car. The boys are almost freezing, but there is hardly any grumbling. They think it’s all part of it.

Hennie is allowed to participate in the Tour de Junior in Achterveld. They are all seeing him off (from right to left): sister Maria, brother Frans on the moped, Hennie, father Gerard, and mother Johanna among Hennie's cousins.

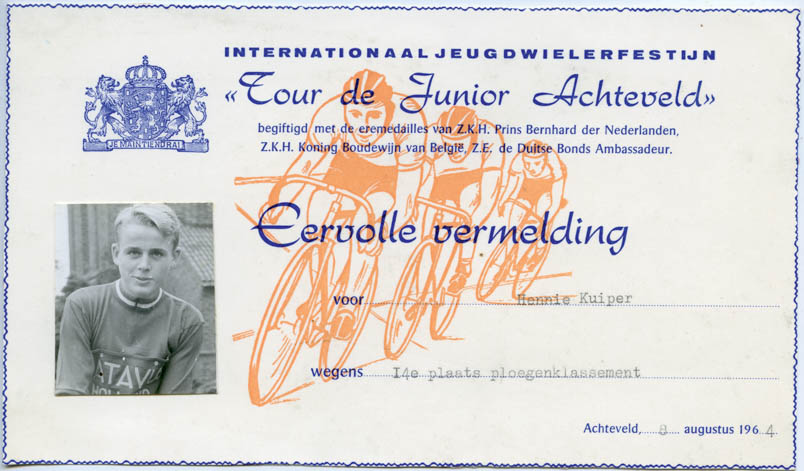

Hennie keeps a certificate from his first Tour de Junior. In August 1964, he receives an 'honorable mention' when his team, 'Batavus Rijwielen', with the local Achterveldse favorite Frans Stapelbroek as team leader, finishes fourteenth in the team classification. In 1964, a total of 72 youth riders participate, divided into... fourteen teams.

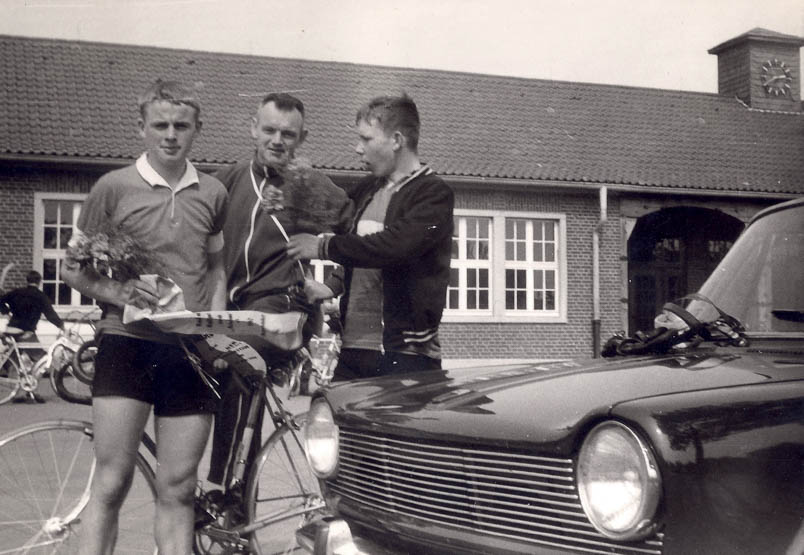

In 1965, Hennie (middle) departs as team leader in the Tour de Junior in the red and white shirt of the 'company team' of 'Holland van 1859 Insurance'. Around Hennie (in the middle) are the other four (from left to right): Adri Raemaekers (14, from Belgium), Tom Kemperman (15, and like Hennie from Denekamp), Ton van Dijk (15, from Mijdrecht), and Jan Oude Hengel (16, from Rossum)

First victory

For Hennie Kuiper, May 15, 1966 is a historic day. For the first time in his career, he wins an official race in Emsdetten, Germany. He is 17 years old at that time. In his two years as a novice, he can cross the finish line with his hands up five times. Usually, he finishes alone. The lack of pure speed makes him a mere extra in the final sprint. He finishes second at least seven times during those novice years, indicating more than average talent. Not everyone is convinced at that moment. For example, Broer Oude Keizer, president and coach of the OWC, Hennie’s cycling club. He is someone with a name in the cycling world, especially in Tukkerland. Oude Keizer has a history as a professional cyclist, having ridden six-day races in the era when riders were on the bike day and night. He is from the time of Jan ‘Kanonbal’ Pijnenburg and Piet van Kempen, illustrious names from a distant past.

Hennie approaches the president with a feeling of pride. After all, he has already achieved two victories at that time? ‘What does Broer think?’ Broer asks him: ‘Do you want an honest answer?’ Hennie nods affirmatively. He expects some praise, but instead Oude Keizer says: ‘You’d better quit.’ Hennie cannot be more disappointed than after this answer. ‘What am I doing wrong?’ ‘Well, you lack speed and it won’t amount to anything that way.’ Ouch, that hits hard. Expecting praise and receiving a mental blow instead. It takes him a while to recover. But then he eagerly accepts the president’s offer to follow a program under his guidance that can turn him into a racer.

Hennie and other ambitious OWC members are subjected to a grueling training regime. Three men endure it: Hennie, Tonny Bruns, and Herman Snoeijink, later the amateur with the most victories in the Netherlands (365). They reap the rewards of their training efforts and make great progress. Broer Oude Keizer makes Hennie strong thanks to his special program, in which interval training plays a major role. Oude Keizer has special massage oil, a mixture of Cajuput oil, camphor spirit, salad oil, and Tyrolean oil. When he prepares the oil, it stinks for days in the Oude Keizer household. Broer is Hennie’s cycling father.

On the day Kuiper rides to gold in Olympic Munich, his trainer at home in Oldenzaal cannot contain his emotions. He sits crying in front of the TV set. Then he takes the flag and hangs it outside on the facade.

The strong bond between trainer and pupil becomes evident when Broer Oude Keizer passes away during a training ride. Hennie shows up at the funeral home, goes to the casket, and stands with his hands behind his back by the coffin for half an hour. He realizes he owes a lot to his trainer. The death of his trainer has slowed down Hennie’s development. The effort he put in under his guidance pays off in races. Not that Hennie wins much - he is simply not a sprinter - but he is far from being a wallflower in the peloton. He is a pure attacker, constantly attacking and enjoying himself on the bike. Hennie enjoys it all, finds everything beautiful. And above all, he wants to discover what else is out there in the (cycling) world.

Hennie feels at home in the jersey of bicycle dealer Han Wurtz from Deventer

On May 15, 1966, Hennie Kuiper wins his first race in the German Emsdetten. On the right training partner Ben Wolkotte. In the middle mechanic Bertus van der Horst

Club championships of 1969 in Dronten. OWC finishes 57th in the B-category. From the front: Hennie Kuiper, Tonnie Wissink, Theo Franke, and Leo Engbers

As a first-year amateur, Hennie participates in the Ronde van Nijverdal in 1968. With Zwier Sellis from KWC (Kamper Wieler Club) from Kampen in his wheel. The children from the neighborhood have little eye for it.

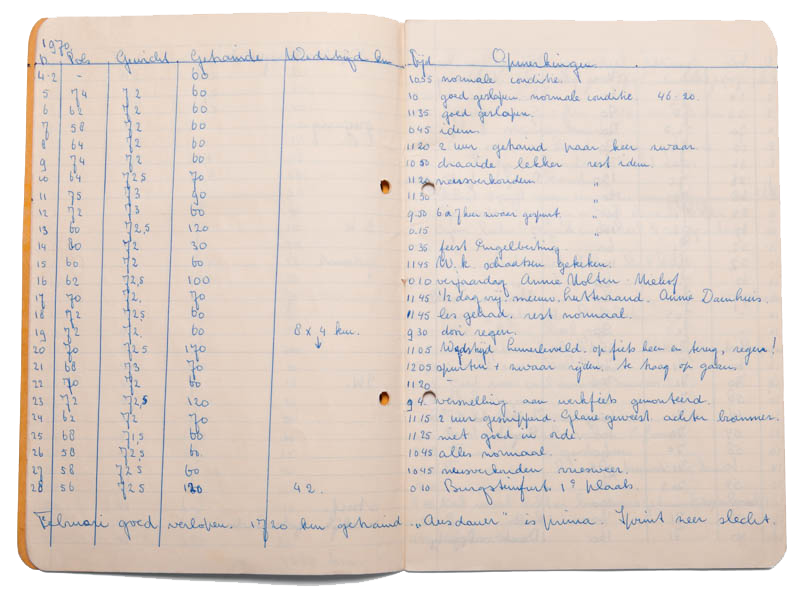

Hennie Kuiper takes the profession of a cyclist seriously at an early age. He meticulously keeps track of his performances and progress. Look at the bottom line, which contains the conclusion of the month of February 1970: 'February went well. Trained 1720 km. 'Endurance' is great. Sprint very poor'

In a 2cv to the first cobblestones

In 1968, Hennie has a modest sponsor: Han Wurtz from Deventer, a bicycle dealer who helps a number of cyclists with equipment under the name HWD. His trainer Oude Keizer tells Hennie: ‘If you want to become a racer, you have to race in Belgium. You buy a newspaper there and look in the cycling section to see where a race is being held that day.’ His teammate Hans Troost is the proud owner of a Citroën 2cv, also known as a Lelijke Eend, in those days. If Hennie wants to go to Belgium, he has to report to Hans in Deventer. So, Hennie loads in his bag on the handlebars the provisions carefully prepared by mother Johanna: a thermos with tea, rice, chicken legs, and bread. He rides to Oldenzaal to continue the journey by train towards Deventer, where Hans and his 2cv are waiting.

At Valkenswaard, the duo crosses the border, buys a newspaper, and sees two races listed for that day: one near Menen, at the French-Belgian border, and another in Kruibeke near Antwerp. Hans thinks it’s all too far and wants to go home. Not Hennie. ‘I absolutely want to race.’ It takes some persuasion, but Hennie gets his way. The journey to the race is already a great celebration for Hennie. They drive through the Kempen, past Herenthals, the hometown of the great cycling hero of those days: Rik Van Looy. ‘It made me happy. That already gave me morale for the race.’ Near Antwerp, the duo exits the highway. They come across a race but quickly realize that they are not amateurs but professionals. Where is the race for amateurs then? The person they ask looks a bit confused. ‘Ah well, you mean the enthusiasts? Then you have to go straight ahead.’ How far is that? Half an hour, is the answer. They arrive within five minutes. The Flemish person still calculates in the time it takes to reach the destination on foot.

The Dutch riders register for their race numbers. They have to pay 20 francs for insurance, 180 francs deposit which they will get back when they return the race number. There are big names at the start of the amateur race. At least big names in the eyes of Hennie Kuiper. A rider like Henk Benjamins for example. The course turns out to be a big surprise for the Dutch riders. It starts with an asphalt road, then the riders turn left and… encounter impossible, gigantic cobblestones ahead of them. Hennie doesn’t know what’s happening to him. The wheels bounce from one stone to the next. It is oppressively hot that day. But the sky darkens, and when the race is well underway, an incredible storm breaks out.

Enjoying Misery

The rough cobblestones become extremely slippery. It feels for the riders as if the road has been smeared with green soap. The inexperienced boys from the east of the northern neighboring country not only struggle to keep up with the pace, they also have to stay upright. The latter - staying on the bike - is more or less successful; the former - keeping up with the pace - absolutely not.

Hennie is passed by one rider after another. This continues until first the peloton and then also the last straggler disappear from sight. But he doesn’t give up. He would rather chew on his spokes than give up. Hennie pushes his bike all alone. The Tukker reaches the liberating finish line as the very last one. His first experience with cobblestones is now behind him.

When he - more dead than alive - crosses the finish line, he says to his teammate Hans Troost: ‘I have never been so broken in my life.’ He is directed to a garage where some folding chairs are set up with a bucket of water in front of them. ‘No shower, no heated room to relax and recover.’ But Hennie doesn’t complain. He considers the whole day as a wonderful adventure. He enjoys it. Afterwards, the bikes are loaded onto the roof and the long journey back begins. Somewhere between Holten and Markelo - before the A1 highway was built - Hans Troost stops the car. Hans had already mentioned before leaving: ‘I can’t drop you off at home because I have to go to my father’s birthday party.’ Hennie takes his bike and rides the fifty kilometers to his parents’ farm. At two o’clock in the morning, he shows up at his parents’ bedside. Hennie has returned from his first cobblestone race.

Hennie rides attentively and keeps an eye on the competition in the Tour of Tegelen in 1970

Hennie shows off his outfit when he starts racing for the amateur team of Ketting Wielersport in 1970

Visible satisfied, Hennie Kuiper crosses the finish line at the club championships in Oldenzaal. On the left, judge Ben Roesink, on the right of Hennie in a black duffel coat OWC chairman Herman Nijhuis with next to him (applauding) Willy Wissink

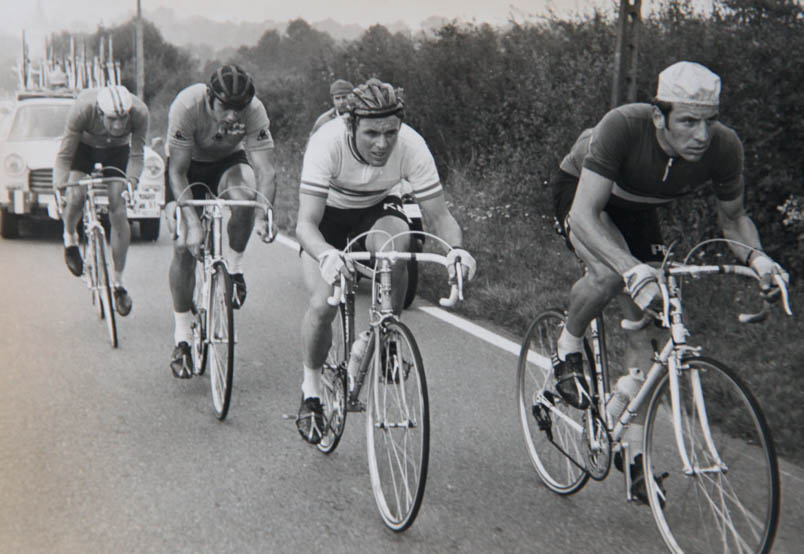

In the third stage of the Tour de l’Avenir from Niort to St. Yrieix on September 15, 1972, Hennie makes a bid for power. After 79 km, he escapes alone and later receives support from the Czech Aloïs Holík, the Frenchman Claude Magni, and the Italian Tulio Rossi. The breakaway will not hold. Here, Magni is leading.

On 8 April 1972 - a week after his victory in the Tour of Drenthe - Hennie already falls in the first kilometers of the Tour of North Holland. In a race dominated by the wind, he eventually still finishes 23rd.