Finally: a sponsor

In the present day, winning an Olympic title guarantees you a professional contract. This was very different in 1972, although the overshadowing of that title by the horrific terrorist events surely played a role. Indeed, Hennie does not have the aura of defeated champions like Francesco Moser or - to a lesser extent - Freddy Maertens. But it is strange that no sponsor comes forward in the months after the Olympic championship.

He himself does not have concrete plans to turn professional. Fedor den Hertog, who has been ripe for the ranks of professional cyclists for years, still hesitates. And Hennie also has his doubts. “Professionals are too often associated with things like doping and collusion.” Those unfamiliar with the sport categorize cyclists as ‘untrustworthy people’.

Initially, Kuiper’s plan is to secure a position as a work planner at the company where he works through a study. Besides, there will surely be time left over for cycling. He thinks long and hard about it. He is a thoughtful person from Twente.

An offer comes from the cheerful team manager Ton Vissers, who does not have the best reputation in cycling circles despite his optimistic nature and joyful manner. At the presentation of Herman Krott’s Amstel amateur team, where the cycling press is massively present, Vissers employs the tactic of surprise. He pushes a contract under Hennie’s nose, which he only needs to sign. The press is already there anyway: that means immediate publicity. But Hennie does not give in. He wants to adjust some things in the contract. Vissers’ promise, “that will come later,” he does not take seriously and he sticks to his refusal. Not long after, Kuipers receives a letter from Vissers full of legal terms stating that he will not be offered a contract for now. As if he had begged for it…

Later, Kuiper runs into Krott, the team manager of the renowned Amstel team. Which team will he ride for next year? When Hennie replies, “With Ketting’s amateur team,” Krott falls off his chair in surprise. Because, according to Krott’s reasoning, Kuiper is ready to join the ranks of professional cyclists. He calls far and wide, but all teams are full. Until Krott finds success in Germany with Robert Kahl. He runs a successful mattress business. Under the name Rokado, he has assembled a professional team with stars like Herman Vanspringel, Georges Pintens, Tony Houbrechts, and Gerben Karstens. He also decides to form a team with upcoming talents, mainly from Germany. Hennie, who lives so close to the German border, is added to the Ha-Ro team, a name hiding behind it the first names of the sponsoring couple: Hannelore and Robert.

Debut with attack at the pros

Team manager is Rolf Wolfshohl, who has mainly made a name for himself as a cyclocross rider. Wolfshohl’s lessons are absorbed by the debutant like God’s word by an elder. He absorbs all knowledge, more eager than ever before. He wants to race, to show what he can do. His entrance into the professional environment is far from grand. While contemporaries like Maertens and Moser are heavily courted with money when they switch teams, Hennie – despite being an Olympic champion – barely manages to secure a contract. But the man from Twente doesn’t take this lying down: he must and will prove himself.

In his first Paris-Nice, he tells his teammate, Karl-Heinz Muddemann: ‘I’m going to attack.’ His move is countered by riders from Eddy Merckx’s dominant Molteni team. An hour later, Hennie attacks again only to be caught by the Molteni riders once more. As he prepares for a third attack, the seasoned Molteni rider Vic Van Schil catches up to him. The spirited youngster needs some calming words. Van Schil tells him: ‘Take it easy lad, your time will come.’

Hennie is impatient for success, eager as he is. He quickly proves to be the only one from Ha-Ro’s development team who can hold his own in the professional environment. His first major achievement – fifth place in the Amstel Gold Race – is a real sensation. Not just because of the result, but especially because of how it was achieved.

While all the big teams check in at South Limburg the day before the race, there is no budget for overnight stay for the Ha-Ro team. Hennie gets out of bed before dawn. Ine has taken over the caring duties from his mother, but the tradition remains. So, he brings along the familiar old blue pot containing rice with raisins, a chicken leg, and a thermos of tea. This is his pre-race food package, the fuel for the race. He then sets off from Oldenzaal in his Renault 4 towards his parental farm after moving there following his marriage, where his brother Jos drives him to the start in Meerssen.

The weather is wintry bad: wet snow, cold rain. A group of forty riders breaks away from the peloton. Debutant Kuiper attacks on a climb and quickly gains a lead. Then comes the car of race director Herman Krott and national coach Joop Middelink behind him. The duo is extremely enthusiastic. Joop Zoetemelk and Eddy Merckx chase after the debutant. He quickly eats a Mars bar and then Merckx-Zoetemelk catch up on Fromberg. From that moment on, Merckx takes command. The pace is so high that Zoetemelk has to let go. Hennie is surprised. He races in second place for a while. ‘That was something. Second in the race behind the great Merckx.’ Eventually, he is overtaken by Walter Godefroot, Herman Vanspringel, and Frans Verbeeck. No shame in that. Fifth place is an excellent performance for a debutant.

On 19 December 1972, Hennie Kuiper signs his first professional contract. He will ride for Ha-Ro, the team of Robert Kahl, who is pointing to Hennie on the left in the photo where he should sign. Brother Oude Keizer, Hennie's first coach, looks approvingly at where his guidance has led.

In the Amstel Gold Race of 1973, Hennie Kuiper makes an immediate impression as a rookie professional. He goes into battle in front of the 'Rijkspolitie' car.

First professional victory: hellish booing

Hennie is immediately after the Gold Race missing his clothes. Team leader Rolf Wolfshohl has taken off with his clothing. In a training suit borrowed from Joop Zoetemelk, he hurries in journalist Peter Ouwerkerk’s Mini from Het Vrije Volk to the showers, where a caretaker is waiting for him. The plan is for him to fly from Brussels to Carcassonne by plane for the Tour de l’Aude, which starts in that city the next day. Due to the late arrival of the Gold Race, Hennie cannot make the flight. Improvisation is needed. Kuiper leaves for Dortmund that same evening, the headquarters of his sponsor. His director, Robert Kahl, has a private plane, with which he will fly to southern France the next day. Early in the morning, Hennie gets out of bed. At the airport, he has to scrape ice off the windows with the pilot. Hennie sits next to the pilot in the mini-plane. The pilot throws him maps and says, ‘You are now my co-pilot.’ This is how the newly minted professional travels to Carcassonne for the four-day stage race Tour de l’Aude, which starts later that same day. The French organizers are pleased with the arrival of the Olympic champion. His participation is announced grandly in the streets of Carcassonne.

In the first stage of that race, he is eliminated by a flat tire, having to wait so long for a new wheel that he is instantly out of contention for a high placement. Kuiper seeks revenge. ‘Outwardly I am calm, inwardly I am a volcano. I can charge myself up tremendously.’ On the second day, in the stage to Bram, a 193-kilometer road race, he attacks and gets away with Belgian Wilfried David and local favorite Pierre Martellozzo. David is dropped. In the tumultuous sprint in the streets of Bram, home rider Martellozzo is as determined for victory as Kuiper. Neither are sprinters. Martellozzo constantly moves from left to right towards the barriers. But Kuiper cannot be stopped; the anti-sprinter rides gloriously to victory. When he finally crosses the finish line first, he is met with a hellish booing from the massive crowd that is deeply disappointed. The local hero is defeated, while Hennie remains stoic amidst the jeers.

It is April 9, 1973, and his first victory as a professional has been achieved. Beautiful of course, but when he thinks back to the stage in Paris-Nice a few weeks earlier, from Manosque to Draguignan, he realizes that this first victory could have come earlier. There in Draguignan, just before the finish line, he had a comfortable lead over his competitors, triumphantly raised his arm in celebration, but was overtaken at the last moment by Belgian sprinter Rik Van Linden: a costly lesson for debutant Hennie Kuiper. He also gets his first taste of the famous classic Paris-Roubaix. Team leader Rolf Wolfshohl promises Hennie a bonus of one hundred D-marks if he finishes in the top thirty. It’s one big adventure for the young Tukker. It’s tough. The weather is bad. So bad that out of 138 starting riders, only 35 reach the finish line. It’s suffering. But oh, how Hennie enjoys every meter he covers. It’s beautiful! Hennie misses Wolfshohl’s bonus. But he celebrates his 31st place, 27.36 minutes behind Eddy Merckx, as a triumph. The famous Luis Ocaña finishes less than two minutes ahead of Hennie in 29th place. It’s fantastic!

Eddy Merckx and Joop Zoetemelk catch up with Hennie Kuiper (71) in the Amstel Gold Race of 1973. Later, Merckx will give a strong burst of speed and gloriously cross the finish line in Meerssen as the winner.

Eddy Merckx continues in the Amstel Gold Race of 1973. Joop Zoetemelk and Hennie Kuiper keep the wheel

Cold shower

In the Championship of Zurich - in those days a tough and highly esteemed race - he rides to second place. Only the Belgian André Dierickx can prevent him from victory in a sprint with four. The weather is dreadful and the riders cross the finish line shivering. A cold shower awaits them - quite literally. Warm water is not available. But Hennie doesn’t care. When Hennie’s fellow region Wim Albersen hears the story, he is not surprised at all. He has a lot of contact with the neo-professional in the early months of 1973 and trains regularly with him. He remembers that after the central training at Papendal, Hennie always turns the shower to cold. ‘Because, as Hennie’s reasoning goes, when you’re on top of a mountain and you have to descend, you get freezing cold.’ And he wants to be prepared for that. He trains his body, already thinking about ‘later’.

Henk Poppe recognizes that. In his eyes, Hennie is a very serious guy. Poppe might grab a bottle of milk from the fridge after a training session, but Hennie doesn’t want that cold stuff in his stomach. ‘He wants warm tea. Hennie really does everything to become a better cyclist. In his thinking about the race, he is already ahead of everyone else,’ Poppe says. Poppe is the big promise around the turn of the decade between the sixties and seventies; blessed with a razor-sharp sprint, lung capacity that gives him the ability to ride solo, good race insight, and a captivating style. National coach Joop Middelink describes Poppe as a ‘round’ rider: someone who rides smoothly, effortlessly letting the kilometers flash by under his wheels. On the other hand, Middelink qualifies Hennie as a ‘square’ rider: a worker.

‘Difficult style’

Poppe, who currently shares his life with an artist in Nijverdal, remembers that initially in the peloton there were derogatory remarks made: ‘that guy can’t ride a bike.’ He has, what Poppe calls, ‘a difficult style’. But Henk Poppe does recognize the qualities of his fellow countryman. Because even though it may not look pretty, Hennie does move forward. And very fast too. Poppe points out the impressive list of achievements of the farmer’s son. Kuiper’s fellow countryman as a rider for the Frisol team is also part of the professional peloton and wins the first Tour stage ever ridden on British soil in Plymouth in 1974, ahead of top sprinters Jacques Esclassan and Patrick Sercu. In his second year with Frisol, 1975, Hennie is occasionally his teammate and sometimes also his roommate. He knows from experience how difficult it is to maintain oneself in the professional peloton, both physically and mentally.

Poppe also rides in foreign stage races with Hennie among amateurs. There, he remembers, Kuiper truly finds his way up. He applies Joop Zoetemelk’s motto: races are won in bed. When Poppe gets on the bus after a stage in one of those foreign stage races, he is deadly tired, but can’t sleep. The bus has barely left, and Hennie is already deeply asleep, envyingly so. He is already focusing on his recovery, while most competitors still have racing adrenaline rushing through their bodies. Henk Poppe definitively leaves the peloton in his second year as a professional. He is sickened by the doping culture. He sometimes talks to Hennie about the questionable practices in the peloton. But where Poppe succumbs to it, Kuiper closes the curtain and goes his own way. Forty years later, Henk Poppe sees things differently than in 1974. He would do it just like his fellow countryman did back then: not care about anything. If he could do it over again, he would take three years for it and if he still hasn’t succeeded as a rider by then, he can always quit. ‘I wouldn’t impulsively turn my back on the peloton like I did in 1975.’

In his first year as a professional cyclist, Kuiper is increasingly used as a rider for the main team: Rokado. He has little business with the development team Ha-Ro. When a team needs to be formed for the Giro d’Italia, Hennie is selected. Initially he acts mainly as a domestique, but as the stage race progresses, Hennie proves to be perfect for that role. He excels far beyond the level of a domestique. Kuiper exudes health and never slackens. Yet his starting position is very different from that of Italian Francesco Moser or Freddy Maertens, his competitors from the previous year’s Olympic road race. Moser is seen as Italy’s promise for the future. Stories about Francesco adorn all sports pages from the start of the season. From day one he is surrounded by helpers. Freddy Maertens doesn’t have it any different. At the Belgian Flandria team he is assigned domestiques at the beginning of 1973. The renowned Walter Godefroot takes on a sort of mentor role.

Hennie - still the Olympic champion - has to figure it out mostly on his own.

The experts within and outside the peloton quickly realize that the small Tukker has a lot to offer. While Francesco Moser is supported by a complete team, he finishes fifteenth in the Giro d’Italia, just one place ahead of Hennie Kuiper. And when Hennie comes out even stronger in that same Giro d’Italia a year later, the peloton knows that Kuiper is a rider who can play a leading role in any stage race. He would have definitely finished in the top six if he hadn’t landed on a concrete edge with his back during a fall in a tunnel near Limone Sul Garda on Tuesday, June 4th. Three days later, in the stage to Bassano del Grappa, on the penultimate day, the consequences of that fall become unbearable and he is forced to abandon.

Offer Merckx: Hennie refuses

Eddy Merckx sees Kuiper as an ideal helper. Merckx has gathered around him a select group of riders who are physically so strong that they could also act as team leaders in any other team. Racing for ‘Eddy the Great’ is considered an honor by them. And who wouldn’t want to ride in the service of the best cyclist the world has ever known? Firmin Verhelst is the manager who takes care of Merckx’s affairs. After the Giro, he approaches Hennie Kuiper and invites him to join Merckx’s select group.

‘That was something. I felt very honored. Racing with Merckx, the best cyclist in the world…’ Nevertheless, the Dutchman does not need much time to express his gratitude for the honorable offer, but still decline. No, Hennie has his own plan. He wants to see first how far he can go in this sport on his own strength.

By the end of 1974, Hennie’s team Rokado is done. Riders and staff need to look for a new place. Hennie Kuiper finds it at the oil company Frisol, which after sponsoring a cycling team in the amateur category for several years, built a professional team around international amateur top rider Fedor den Hertog in that same year 1974. For Nico de Vries, who made a fortune in the oil trade, Fedor is an idol, who - according to De Vries - is on par with Eddy Merckx. Fedor’s first year as a professional ends in a big disappointment. He doesn’t achieve any victories, doesn’t perform well in any important race. But De Vries’s confidence in his protege remains unbroken. He informs Piet Libregts, the team manager whom De Vries always refers to as ‘my sports director’, that reinforcements are needed by mid-1974. This reinforcement is mainly intended to help Fedor in his rise to the highest ranks of the peloton. And one of those intended helpers is Hennie Kuiper. At least that’s what De Vries has in mind, although he doesn’t mention it during the contract negotiations. De Vries receives the Tukker on his luxurious yacht on the French Riviera. At that time, Hennie is an Olympic champion, has had two exceptionally successful debut years and is considered a great promise by experts. The Frisol director offers him a contract with a basic salary of twenty-five thousand guilders. It’s not much for an Olympic champion, but cyclists were generally poorly rewarded during that period. It’s about half of what his protege Fedor receives in his first year at Frisol, but Hennie doesn’t know that. He asks De Vries how much winning a classic race would earn him. But De Vries brushes off that question. For such a salary, De Vries expects Kuiper to win a classic race anyway. ‘But what if I become world champion?’ asks Hennie. De Vries snatches the contract off the table. He writes with a pen the following text, which literally (including spelling mistake) reads: ‘If Kuiper becomes world champion then Frisol pays Kuiper fl. 15,000 =.’

There, that’s settled.

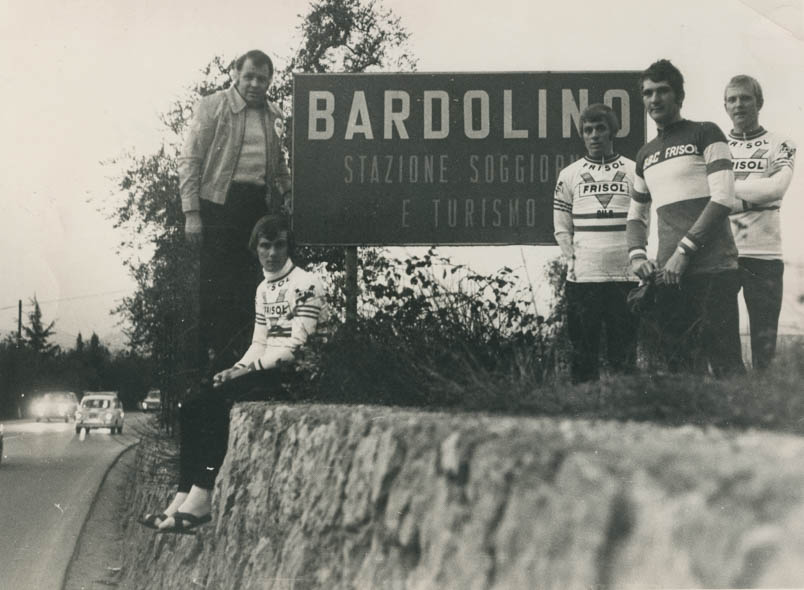

Frisol is a team with mostly young, inexperienced riders, with a team leader, Fedor, who has spent his best years in the amateur category. In addition, there is a great promise, Hennie Kuiper, who is not recognized as such by sponsor boss De Vries. Because no matter how surprisingly strong the men sometimes race, if Fedor doesn’t win, De Vries is disappointed in the team. And because Den Hertog doesn’t win anywhere in his first season as a professional, Nico de Vries is in a bad mood. Frisol’s first training camp in 1975 is set up in Bardolino on the southeastern side of Lake Garda. At the beginning of the new cycling year, eighteen road cyclists have contracts with Frisol; only six of them are chosen for the training camp in Bardolino: Cees Priem, Henk Poppe, Theo Smit, José De Cauwer, Gerard Kamper and Hennie Kuiper. Den Hertog can prepare for the road season in France with caregiver Rudy Bergmans - specially hired by De Vries for Fedor. The others have to make training kilometers in the Netherlands and Belgium.

In September 1974, Gerben Karstens wins Tours-Paris. Hennie Kuiper does not finish, but ends up in a beet field. Just like Lieven Malfait from Watney and - sitting on the side - Michel Pollentier. A year later, Hennie ends up in a beet field again in Tours-Paris, but this time in the rainbow jersey.

On 9 April 1973, Hennie Kuiper achieves his first professional victory in Bram during the second stage of the Tour de l’Aude. The French newspaper La Depèche du Midi is still getting used to it. They headline: Olympic champion 'Kiuper'

‘José must have thought…’

Three double rooms are available for the six riders. Kuiper is assigned to the Belgian José De Cauwer. The two barely know each other. Hennie has dressed warmly, pulled a woolen hat deep over his head, and looks somewhat suspiciously at his roommate from his bed. ‘José must have thought: who is this person,’ he realizes afterwards.

At that moment, José doesn’t think much; he knows that Hennie Kuiper is an Olympic champion and he has encountered him at a race before. He has already experienced that Hennie is not a ‘big shot’ as they say in Flanders. The Olympic title has not led him to act like a star.

José and Hennie are opposites in many ways, but they also have similarities. Neither of them are city people, both are fascinated by nature. José is a great bird catcher, always busy with bird nets; we already know Hennie as someone who enjoys wandering through nature.

What also helps is that José, like Hennie, has a speech impediment. Shared pain is half the pain. Although not to the extent that Hennie struggles through sentences, José also sometimes gets stuck on a word. José is extremely assertive. Anyone who scores 1-0 verbally against the Fleming can immediately expect a response from the Belgian; he outdoes the opponent, making the score 1-2. He is as modest in stature as Hennie, standing at only one meter and seventy-three centimeters tall. And while the small Tukker is absolutely fine with being called ‘the small one,’ it makes José furious. He feels humiliated when people tease him about his short stature. In terms of sportsmanship, he holds his ground: he is sharp and agile, but do not mockingly call him ‘small’ or you’ll regret it. He not only figuratively bites back but sometimes literally bites into the arm or hand of his tormentor.

Like Hennie, he does not come from a cycling family. Cycling is not something they appreciate in the family near Antwerp. It is a sport they do not want to be associated with. When he is 14 years old, he has to start working; help support the family. He later follows a training course in cabinet making and then a technical drawing course. But during that time, he is already hooked on road cycling, which he purchases with financial help from his sister Paula. ‘Against my father’s wishes.’ But the racer-José cannot be stopped. Initially, he has little success, but later, as a junior, he finishes in the top three 37 times out of over a hundred races he competes in. He gets his first professional contract with the modest team of Hertekamp and wins two races in his first year, one victory of which is a real sensation. In a final sprint, he leaves behind two big names: Roger De Vlaeminck and Rik Van Linden. He moves for one season to the French team Sonolor of Jean Stablinski before Piet Libregts recruits him for Frisol. Libregts remembers him from his amateur days and the Belgian made a good impression on him then.

‘Do you know how fast you can ride?’

José and Hennie find each other in that first week in Bardolino. Although they are totally different, they complement each other well. De Cauwer may have a strong aversion to ‘big heads,’ but he believes that the Olympic champion should show himself more as such outwardly. He allows himself, as De Cauwer puts it, to be ‘sat on his head’ and is occasionally ridiculed. José cannot stand for that. He defends Hennie, also guides him in the world of cycling and beyond. Better than Hennie, he feels a race. Reading the race is still a strong point of José De Cauwer, as he demonstrates in his work for Flemish television. As Michel Wuyts’s sidekick, he is the undisputed master of analysis. De Cauwer is already impressed by Kuiper’s qualities during the first training sessions. It is he who says: ‘Do you know how fast you can ride, how good you are?’ The penny drops for Hennie. He becomes convinced of his abilities. José notes that Hennie has more endurance and determination than all the others. Especially when the kilometers start to count, the course is grueling, and the weather conditions are unfavorable, his Dutch roommate proves to be considerably stronger than himself. Not that De Cauwer lacks qualities himself. They have said of him: more head than legs. But that would be unfair to De Cauwer. He is a rider of both head and legs, although he may not match up to the top riders in terms of legs. Anyone who can work for someone who becomes a great rider like Kuiper, who thanks to the advice of team leader Hennie, takes the leader’s jersey in a stage race like the Tour of Spain, and who has beaten both Rik Van Linden and Roger De Vlaeminck in a sprint, must also possess great qualities themselves. While he may not be as strong as the big stars, he is smart; very smart indeed.

In the major opening race of the 1975 season, Omloop Het Volk, José De Cauwer finishes a respectable third behind winner Joseph Bruyère and Patrick Sercu after spending the whole day at the front of the race. In Paris-Roubaix, the queen of classics, De Cauwer stands out again, this time with a twelfth-place finish. And Kuiper always finishes far behind the man who has now become his regular roommate. ‘That’s not right,’ thinks De Cauwer. ‘He is better than me, but he cannot position himself well. Something needs to change.’ He introduces Kuiper to Luc Vandecavije, a very calm and reliable sports doctor. Together, doctor and teammate support the rider from Twente. For the professional cycling world, it becomes increasingly clear: De Cauwer is Kuiper’s domestique. Roger De Vlaeminck and his companions mock him. ‘Pffft… Kuiper isn’t a team leader? He isn’t a captain?’ No, thinks José, he may not be a leader, but he can race well. And the more people make fun of Hennie, the greater José’s willingness to defend him becomes.

The servant who is not a servant

No one has told him how to relate to Hennie. Hennie has never asked him to act as a support and confidant, but José quickly realizes that Hennie is better than him, especially stronger. De Cauwer naturally has considerably more pure speed, but in a big race, Hennie is stronger as the competition progresses. Hennie has a strong engine. De Cauwer draws his conclusions: ‘For the big work, Hennie is more suitable than me, but I can help him make the right decisions.’ He never feels like a servant. Some ask him how it feels to be a servant of Hennie Kuiper. But José has never considered himself as such. They have a company together - a kind of BV - in which each has a separate role. They work together and sell themselves together.

At the first training camp of Frisol, Hennie Kuiper is one of the chosen ones to travel to Bardolino. The rest of the team stays behind in the Netherlands and Belgium, while Fedor den Hertog has traveled to France with caregiver Rudy Bergmans. From left to right: Theo Smit, Piet Libregts, Hennie, Cees Priem, and Henk Poppe

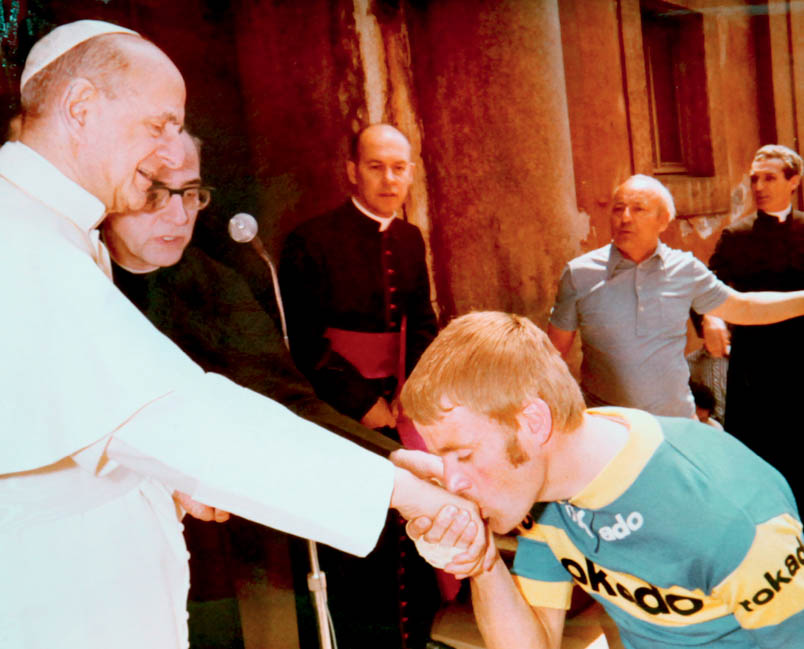

Before the start of the 1974 Giro d'Italia, Hennie Kuiper receives the blessing from Pope Paul VI. That helps. Kuiper rides so impressively in 1974 that Eddy Merckx's manager asks if he wants to join Merckx's team. Kuiper declines the offer.

Hennie Kuiper, cyclist. It's a good thing he's wearing his Frisol outfit, because the setting definitely doesn't exude stardom.

The well-known pose of Fedor den Hertog: he stands on his head. Hennie Kuiper is half hidden behind assistant team manager Edgard De Maere. To the left of De Maere, caregiver Lambert Toebak beams. Caregiver Rudy Bergmans, specially hired for Fedor, keeps Fedor's Frisol shirt in place. To the right of Fedor, team manager Piet Libregts and all the way to the right José De Cauwer.