‘The Games must go on’

When the president of the International Olympic Committee, Avery Brundage, makes his highly criticized statement ‘The Games must go on’ on September 6, 1972, the day before the road race, the cyclists cheer. ‘We were cheering in front of the screen. We could ride,’ Hennie remembers. And ride they do. The start is far from promising for Hennie. In the first lap, he ends up in a near crash with his bike in a ditch, pulls the bike out and starts chasing the main peloton. Along the way, he encounters the first dropouts: boys from Africa and Asia who cannot offer any support. Nevertheless, he manages to return to the peloton. Then there is another crash. This time luck is on his side. He comes across another victim of the crash: Knut Knudsen. It is the Norwegian whom he had seen become Olympic pursuit champion just a few days earlier. ‘He could ride a bit. I had already seen that myself.’ Knudsen starts chasing. Hennie latches on and lets himself be brought back to the front group by the strong Norwegian.

Confident as he is, he later moves forward, attacks and becomes the initiator of a breakaway group in which he discovers, among others, his teammate Cees Priem as well as big names like Italian Francesco Moser, Belgian Freddy Maertens, and Swiss Ueli Sutter. The breakaway group quickly builds a lead of over a minute, but then the pace slows down. One doesn’t want to work for the other. When Hennie looks back, he sees in the distance the peloton approaching led by… Fedor den Hertog, a teammate who should be defending the interests of his compatriots in the breakaway group. Fedor has unprecedented qualities. Hennie calls him the greatest amateur cyclist the world has ever known. Not without reason. But Fedor is also stubborn and selfish. He always rides his own race everywhere and always. Team discipline is usually foreign to him.

Hennie’s Attack

Hennie knows he has to break away before the breakaway group is caught by the peloton. The breakaway group realizes that the peloton is closing in and starts to slow down. The rider from Twente moves to the left side of the road and increases the pace, creating a gap with the rest of the breakaway group, which is caught by the peloton a kilometer later. The riders have entered the final 40 kilometers. Everyone is catching their breath after the intense chase of the breakaway group.

Kuiper is able to extend his lead. Occasionally, a scooter appears next to him, with a man on the back holding up a sign to inform him of his lead. 20 seconds, 30 seconds, 40 seconds. It takes some time before the chase for the solo rider begins. The gap starts to decrease. But Hennie holds on, partly thanks to his teammates Cees Priem, who thwarts every attempt by the Belgian Maertens to close the gap with Kuiper, and Fedor, who now rides in service of the team and keeps the Italian Francesco Moser in check.

The diesel engine Kuiper is unstoppable on his way to a magnificent victory: a solo ride of almost 40 kilometers in an Olympic title fight, crowned with gold. In those days, he does not receive the appreciation and publicity he deserves for his impressive performance. It is not sports, but the attack by the terrorist group Black September that understandably takes center stage. The joy for the medal winners of those days – including judoka Wim Ruska – is therefore tempered. There is no room for extravagant celebrations, although the gold is indeed celebrated within a limited circle. The reactions to the gold are mixed. The majority admire it, but there are also people who express their disapproval, believing that there is blood on the medals. Back home in Oldenzaal, reactions pour in by the sackful. The newlywed bride Ine concludes: ‘A few negative reactions, but the majority is still positive.’

Some comments are outright hostile. As if Hennie is to blame. ‘I also found that attack terrible, but what does that have to do with sports?’ He achieved the highest possible as an amateur in those days: Olympic gold. To this day, he remains the only Dutchman to have ever won gold in the individual men’s road race. He feels no guilt for continuing with his sport after that attack. Can’t you also have understanding for someone who has been looking forward to these Games for years? And isn’t all of this in line with what the Israelis said after that massacre: continue with the Games? Hennie is too involved with his fellow human beings not to share in their shocking loss. At least his family and friends are proud. Hennie is honored by the Oldenzaal Cycling Club (OWC) and by the municipality of Oldenzaal, where he has been living since marrying Ine Nolten. It’s no small feat to ride to victory after such an impressive solo effort. Who can say they’ve done that? No one. Especially not someone from such a non-cycling background as Hennie’s. He will later realize that his Olympic gold will continue to shine throughout his entire career.

At 80 kilometers into the race, a breakaway forms in the Olympic road race with Swiss rider Ueli Sutter (321) on the far left and his compatriot Ivan Schmid (319) at the front. To the left of Schmid is Cees Priem (198), and to the right of Schmid is Hennie Kuiper (194). Riding between Priem and Schmid is later third-place finisher Jaime Huélamo (102). On the right: Freddy Maertens (35) and British rider Phil Bayton (141). Fedor den Hertog has not yet bridged the gap to this group, but will later catch up and play an important role in the finale.

There is little enthusiasm visible in the stands when Hennie Kuiper triumphantly crosses the finish line and becomes the only Dutchman ever to win Olympic cycling gold in the road race

Number 194 is Olympic champion! Hennie Kuiper crosses the finish line in Munich with his arm raised. If you look closely, you can see that he is wearing a 'Ketting' shirt under his Olympic jersey. The letters 'Ketting' are partially visible behind the red and blue stripes on the Dutch shirt.

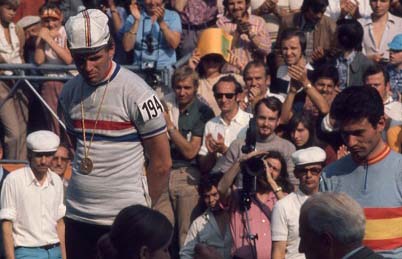

Hennie Kuiper humbly bows his head on the podium after being awarded the Olympic gold medal. On the right, the third-placed rider, Spaniard Jaime Huélamo, who will be disqualified after a positive doping test. Before the national anthems play, Kuiper and silver medalist Clyde Sefton turn a quarter turn (photo below), making it suddenly appear as if the Australian is standing to the left of Hennie.

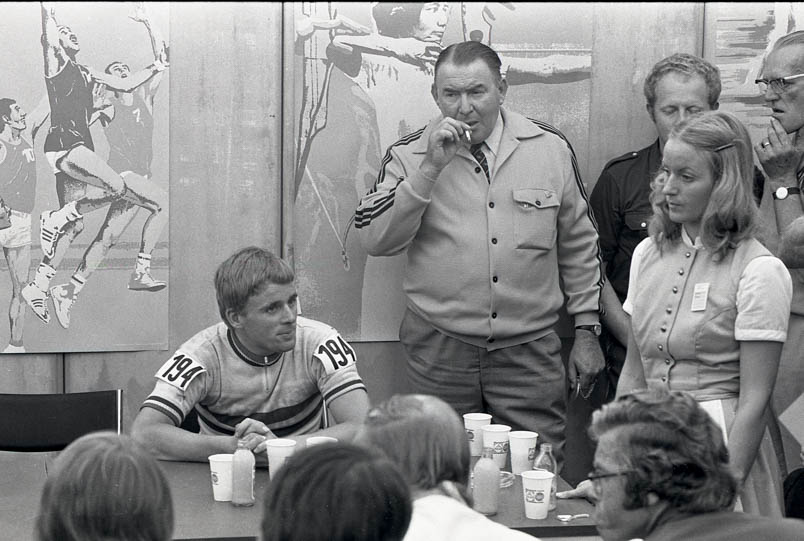

The Olympic champion is speaking to the international press. Behind Hennie Kuiper, Joop Middelink lights a cigarette. In his left hand, he holds Hennie's gold medal. Standing, on the right, are masseur Jan Kuiper and Dutch mechanic Jan Spenkelink. Bottom right: Frans van der Mespel from the Eindhovens Dagblad

Hennie Kuiper lost immediately after the Olympic road race his thirst with a large bottle of cola. On the left his wife Ine, on the right Joop Middelink

Father Gerard and mother Johanna are very proud of Hennie's gold medal, without wanting to place their son above their other children.

At the reception that accompanies the Olympic performances, Hennie Kuiper, Piet van Katwijk, and Fedor den Hertog are showered with gifts. Here, the riders receive a copper kettle from the cycling youth of OWC from Oldenzaal.

Somewhat awkwardly, Hennie and Ine are enjoying a tour. Sitting in the front left of the car is Gerard Kamphuis, with whom Hennie occasionally goes for a training ride. Behind the wheel is the owner Johan Mulder of Hotel Het Landhuis in Oldenzaal.

Hennie cherishes his relics, such as the Olympic gold from Munich 1972