The Games with gunshots

For athletes, 1972 is a special year. The Olympic Games in Munich are on the agenda. Every top athlete wants to compete in that quadrennial event, especially Hennie Kuiper. “In that year, I prepared more seriously than ever. The Olympics: that’s where I absolutely wanted to go. I had to ride so well that the federation couldn’t ignore me. The Olympic arena: that’s what I dreamed of.” Besides the Olympics, there is another important event for him: he wants to marry his childhood sweetheart, Ine Nolten (1948, full name Geziena Maria Theresia), that year. The young couple chooses Wednesday, June 28 as the date, right in the middle of the season. The selectors won’t be happy about that. When he tells his plans to Joop Middelink, the national coach grumbles. The stout man from Amsterdam eventually agrees. He would have dropped anyone else from the team, but he keeps the conscientious Kuiper in his squad. On the wedding day, the entire team, who had raced earlier that day, comes to celebrate the occasion. “It was fantastic.” The newlywed groom proves over the weekend that marriage has not affected his form at all: he finishes second in a criterium in Beltrum, behind Albert Scheffer from Achterhoek.

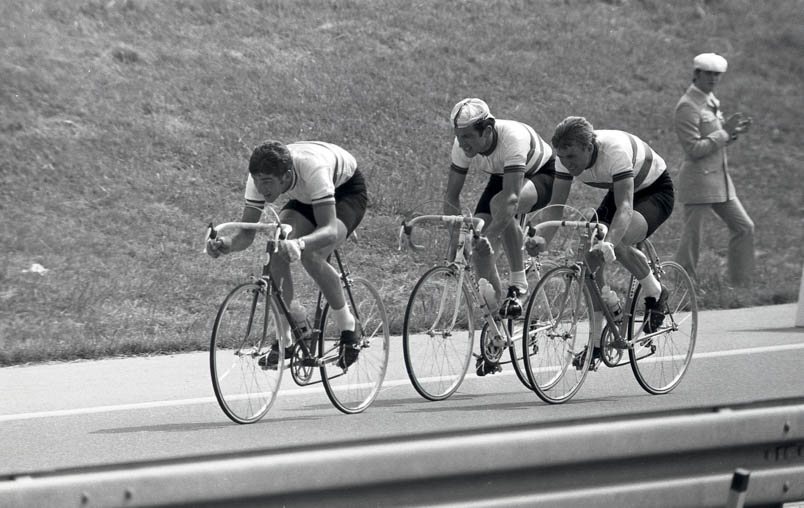

There are two opportunities for road cyclists to participate in the Olympics: the road race and the 100-kilometer team time trial; four spots available for each discipline. In the weeks leading up to the Games, it becomes clear that only two spots are left to be filled. Fedor den Hertog, Cees Priem, and Aad van den Hoek are already secured for the team time trial. For the road race, Den Hertog, Priem, and Piet van Katwijk are chosen. The fourth man for the team time trial must come from several preparatory races. Hennie convinces the national coach. This happens in the final selection race, where it’s between Hennie and Frits Schür. “I made sure that every time I took the lead, I did about fifty meters more work at the front than others.” Never in my life was I so exhausted. Muscle pain all over my body.” The pain pays off with a final selection. Hennie is selected to ride in the team time trial. During the Olympic 100 kilometers, the team is followed by a car with not only the coach but also the chief d’équipe - former sprint champion Arie van Vliet - on board. The team loses Aad van den Hoek early on due to mechanical issues and has to continue with three men. Normally a hopeless situation. But especially Hennie pulls so hard at the front that the team still manages to win a medal: bronze.

Stupidity

Van Vliet asks Middelink: ‘You did select Hennie Kuiper for the individual race, right?’ The coach can’t avoid it this time. The ticket is secured. The fact that the 100-kilometer team later runs into trouble because team doctor Ab Rozijn made the stupid mistake of putting the banned substance Coramine in the bidon, doesn’t play a role in the selection for the individual road race. Coramine is a product that combats fatigue. Aad van den Hoek, who had to abandon the race due to bad luck, is caught afterwards using the forbidden product. It’s strange that no banned substance is found in the urine of the trio who completed the race - Kuiper, Den Hertog, Priem.

Aad van den Hoek is certain that the bidons of the other three riders had the same content. ‘After I dropped out, I drank from the bidon. So there was Coramine in it, although I didn’t know it at the time. Doctor Ab Rozijn had put it in there with the instruction to drink from it halfway through the race. But I didn’t even reach halfway. So it stayed in my body. The efforts that the others had to make probably led to the traces of that Coramine disappearing so much by the time of the control that they were no longer detected.’

The problem was that Coramine was not on the list of banned substances of the world cycling union (UCI), but it was on the IOC list. Doctor Rozijn relied on the UCI list and did not consult the IOC list; an unforgivable blunder.

Incidentally, four years earlier, at the Games in Mexico, a similar issue arose with the 100-kilometer team. There, Limburg masseur Sjeng Collard administered the banned hormone preparation Deca Durabolin to the winning quartet René Pijnen, Joop Zoetemelk, Jan Krekels and Fedor den Hertog. The four were initially cleared in doping control, but a few days later it emerged that Collard had knowingly injected Deca Durabolin into the riders. The Chef de mission of the Dutch delegation, A.F.H. Dokkum, sends Collard home. The IOC is informed about the administration of Deca Durabolin. The question is: will the IOC disqualify the Dutch?

The head of the medical commission of the IOC, Alexandre Prince De Merode consults with the leaders of the Dutch team and comes out with a statement afterwards. ‘The current definition of doping only penalizes the use of those stimulants that are proven by research methods followed. A logical consequence of this position is that the medical commission of the IOC cannot take action against administering hormone preparations, even if they were not administered with the intention of promoting healing.’

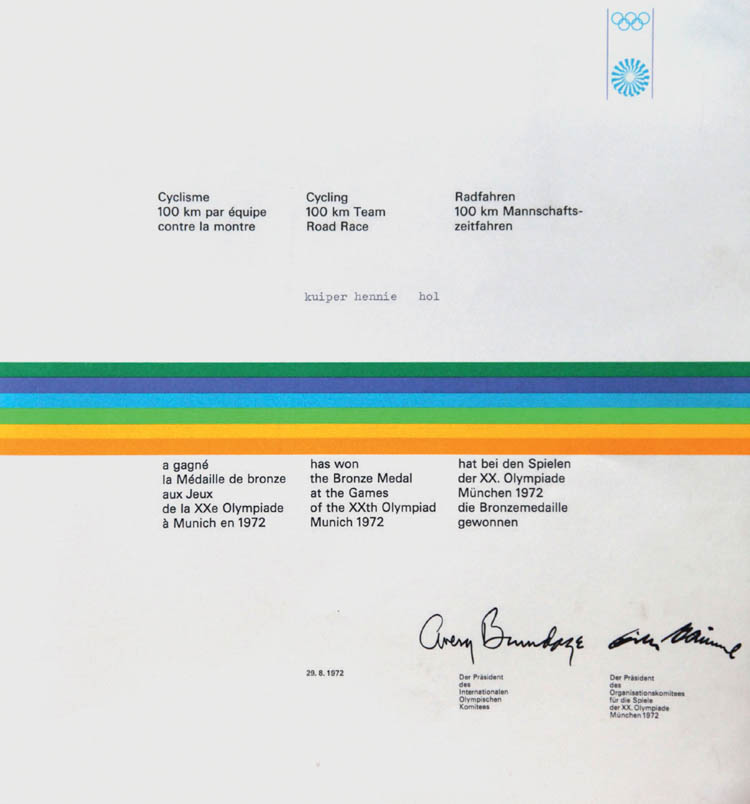

The golden quartet in Mexico gets away with it. And what about the four from Munich? It’s not very clear. The Munich quartet is removed from the results, as well as Spaniard Jaime Huélamo, who loses his third place in Hennie Kuiper’s won individual road race due to Coramine use. But six weeks after the Games, the riders receive an official diploma sent by IOC to their homes. Van den Hoek: ‘And a diploma means you passed, right? The medal still hangs at my home, just like with my three teammates back then. We weren’t such sinners.’

The focus of the four selected riders is on the road race from the team time trial onwards. For Hennie, just being selected is already a dream come true. In the week leading up to the start, he trains with his team in both mornings and afternoons. In the evenings, he goes with his team to track races. ‘I saw a fantastic pursuit race with Knut Knudsen among others. That would come in handy for me later in the road race.’

Hennie is on cloud nine. The usually introverted rider from Twente not only grows physically but also mentally towards his peak form. Fellow Twente native Bert Boom - world champion behind motorbikes in 1969 - serves as a conditioning trainer for Twente cyclists during those years. He describes Hennie as a formidable perseverer, someone who mirrors himself against others and picks up what can make him better from his colleagues’ lessons. ‘Kuiper was very serious. He took his rest on time and benefited from it throughout his entire career.’

Half a century later, Hennie remembers Sanne Wevers’ words, Rio de Janeiro 2016’s golden gymnast, who confidently tells her father and coach on the eve of a decisive day: ‘I am ready.’ That feeling resonates with Hennie from his Olympic days back then. Not that he was sure of victory because in a race with 162 competitors, predicting that is impossible. ‘But I was so excited…’

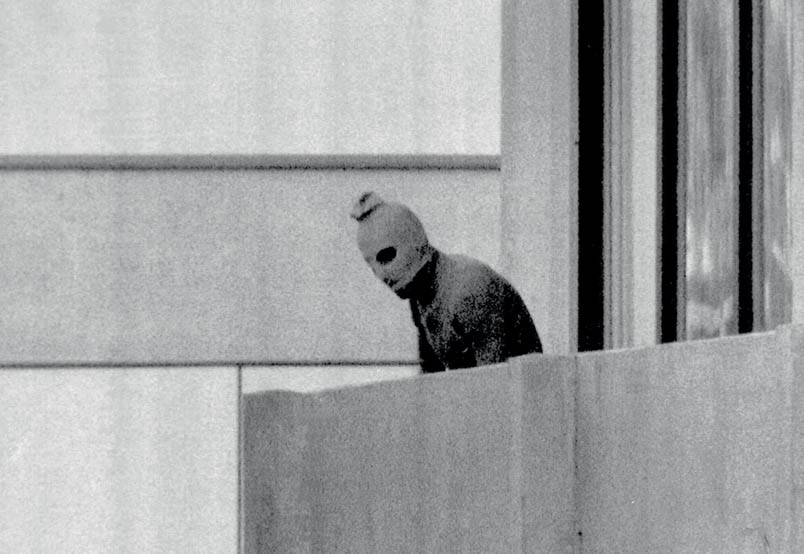

Black September

But then. In the night of 4 to 5 September 1972, men from the Palestinian terrorist organization Black September climb over the fences of the Olympic village and take members of the Israeli team hostage. Shots are fired, there are casualties. Images of this drama spread worldwide. Everyone is in shock.

Most athletes only hear upon waking up that something shocking has happened. Some have heard shots, many others have slept through the gunfire. Slowly but surely, as they make their way to the dining hall, the bizarre reality dawns on the cyclists. They see heavily armed, masked men urging them to hurry. Keep moving, as there could be shooting. In the dining hall, they are told: there was a robbery last night and there was fighting. Coach Middelink wants to keep his men focused on sports training. ‘Come on boys, just train.’ He also thinks about his own mission: to perform as well as possible with the team. And so as little as possible is said about the drama unfolding a few hundred meters away. They cycle, but when the selected riders return, the Olympic village has turned into a fortress. Tanks and soldiers everywhere. There is strict control.

Bit by bit, the riders hear something about what happened. A wrestler has been shot dead. ‘Very sad, of course,’ Hennie thinks, ‘but what now with the Games? Will the whole event be canceled? Has all that training, all those sacrifices been for nothing?’ The cyclists - and not just them - are so focused on the Games that they consider everything happening outside of sports as a distant concern. Reality is lost sight of. The death of a second Israeli is reported. The hostage situation of nine Israelis ends in a bloodbath at the military airfield Fürstenfeldbruck during the night. Eleven members of the Israeli team ultimately die. Five Arab terrorists are fatally wounded in a shootout. A German policeman dies during the operation. In the Dutch camp, there is talk of athletes wanting to go home. Just like the vast majority of the Dutch delegation, Hennie has no intention of returning home. He has fought hard to achieve this.

Criticism erupts in the Netherlands at that moment. A large part of the Dutch public believes that the Games should be stopped. And if that doesn’t happen, Dutch athletes should withdraw. There have been attacks by Palestinian groups before, but this form of terrorism is beyond all proportion. Pressure is put on the Dutch Olympic Committee to have the team return, but the NOC leaves the decision to individual athletes. Six Dutch athletes go home early: athletes Jos Hermens and Wilma van Goolvan den Berg, hockey players Flip van Lidt de Jeude and Paul Litjens, boxing coach Rienus Krüger, and wrestler Bert Kops. One athlete, Bram Wassenaar, withdraws from competition but remains in the Olympic village with the team. The rest of the Dutch representation anxiously awaits what the IOC will do. Most feel that there is little understanding in the Netherlands for the situation. They point out that it is precisely the Israelis who believe that the Games should continue. ‘Leaving means giving in to the Arabs,’ is how those who stay feel.

The wedding day of Hennie Kuiper and Ine Nolten - June 28, 1972 - is embellished by youth members of the Oldenzaalse Wieler Club (OWC)

At the Meesterronde van Denekamp in 1972, five future Olympians are at the start line. From left to right: Hennie Kuiper, Henk Poppe, Fedor den Hertog, Ben Koken, and Cees Priem

Cycling tourism in Munich after the Olympic team time trial. Joop Middelink moves from left to right: Fedor den Hertog, Aad van den Hoek, Cees Priem, and Hennie Kuiper. In the top right, American Dennis Klopper, who provides valuable assistance to the team.

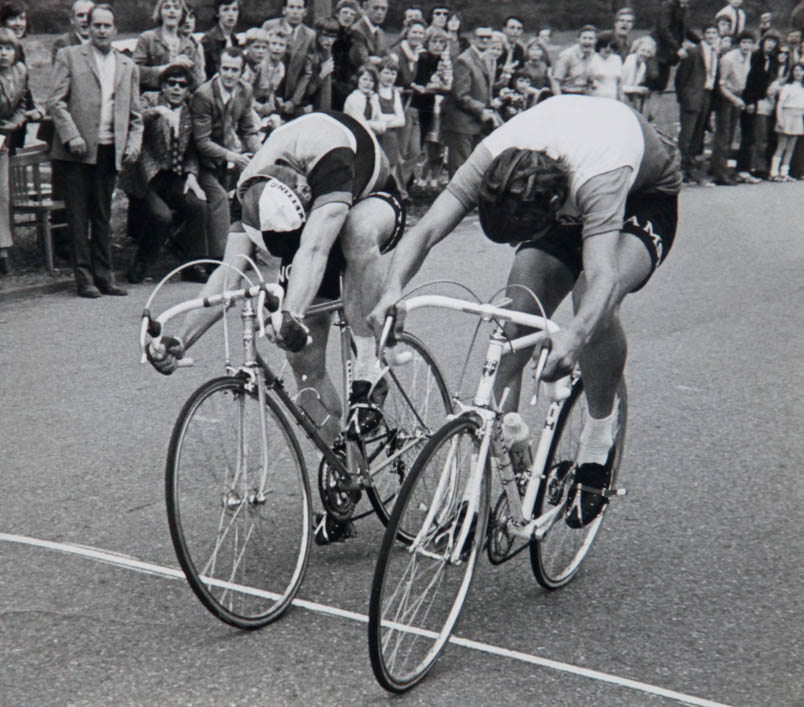

Hennie Kuiper is not a sprinter, but a fighter. Purely on willpower, he beats Arie Hassink in the final sprint of the Ronde van Oldenzaal on May 7, 1972.

The remainder of the Dutch team - after Aad van den Hoek dropped out - in formation on their way to Olympic bronze. Cees Priem is pushing hard, Fedor den Hertog and Hennie Kuiper are gritting their teeth. In the background, an Olympic volunteer in the typical Munich outfit.

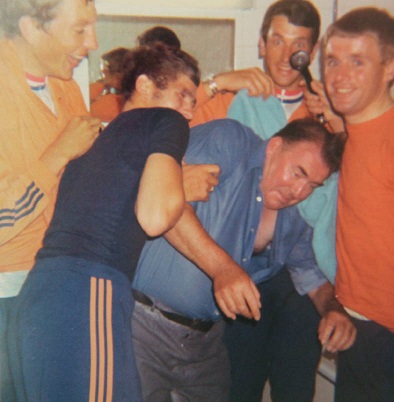

The Olympic bronze is in. Joop Middelink has to face it. Van den Hoek, Priem, Den Hertog and Kuiper are going to give the national coach a soaking. Fedor already has the shower head ready and grins when Middelink has no dry thread left on his body.

On the night of 4 to 5 September 1972, terrorists from the Palestinian movement Black September carried out an attack on the Israeli delegation in Munich: eleven Israelis and a German agent were killed. Hennie Kuiper and the other cyclists who still have to compete are largely kept in the dark.

Six weeks after the Munich 1972 Games - where the team of the 100-kilometer team time trial was disqualified - Kuiper, Den Hertog, Priem, and Van den Hoek receive the certificate of Olympic bronze from the International Olympic Committee.