The frustration of Nico de Vries

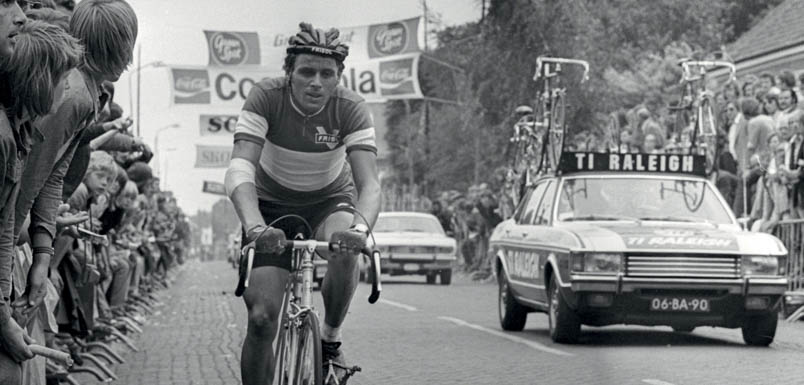

The World Championship of 1975 is - after the Olympic title of 1972 in Munich - another highlight in the career of Hennie Kuiper. Earlier that year he was crowned Dutch champion. Frisol is still the team that matters in the Netherlands. The main opposition comes from Peter Post’s team, Tubes Investment (TI) Raleigh, which will later become the most successful team in Dutch cycling history. In 1975, the team is still in its infancy and does not yet have the quality to dictate the race.

It is bad weather on Sunday, June 22 in Hoogerheide. Hennie has promised Ine to go to bed with the champion’s jersey on Sunday evening after the Dutch championship. The national championship for professionals becomes a race of attrition. Kuiper is so nervous that his stomach rebels and the doctor has to give him pills to ease the discomfort. Despite this inconvenience, he is still in the final. There are four riders left: Joop Zoetemelk, Bert Pronk, Harm Ottenbros, and Hennie Kuiper. Hennie wears down his opponents with a barrage of attacks and wins with a lead of less than 20 meters. He has just completed a tough Vuelta a España, where in the toughest mountain stage he leaves behind all the gathered Spanish climbing elite and only due to sheer bad luck - a sprocket that shatters - he sees the overall victory slip away from him. ‘It was a newly designed sprocket, super light, that the mechanic came up with. It looked great. But, unfortunately…’ Hennie finishes fifth. In the Tour de France, where the modest team wins no less than three stages - through Cees Priem and twice Theo Smit - Hennie Kuiper finishes eleventh. This proves that he can compete with the best even at the highest level. His time trials may not be top-notch, but still promising. Eighth in the first and thirteenth in the second time trial stage. Although he is not yet leading on the climbs, he still shows promise for the mountains.

Fedor

Although the Tukker can present a more than respectable list of achievements, Frisol director Nico de Vries is extremely dissatisfied with Kuiper’s performances. This has everything to do with his frustration over the lack of breakthrough of his great hero Fedor den Hertog. Fedor will not achieve any victories that season, just like in his debut year as a professional cyclist, unless you count the national title at the club championships, a title he must share with his brother Nidi, ‘Dolle’ Dries van Wijhe, and Willem van Boven.

Nevertheless, De Vries announces that Kuiper, who still has a contract running until 1976, can leave as far as he is concerned. De Vries observed in the legendary Tour stage to Pra-Loup, where Eddy Merckx is ousted from the yellow jersey by the Frenchman Bernard Thévenet, that Hennie cannot keep up with the real stars. In the Telegraaf, he states, ‘He seems to be racing more against Fedor den Hertog. Well, that’s not much use to me.’ De Vries has heard that Kuiper has offers from, among others, Gitane. As far as he is concerned, Kuiper can leave after the season. The Frisol director already crosses out his name.

Contract at TI-Raleigh

What De Vries doesn’t know yet, is that Kuiper and his buddy De Cauwer already have an offer from Peter Post in hand, who is in the process of building up his Raleigh team into a top team. The salary at Raleigh is significantly higher than that of his current team: 54,000 guilders. When Kuiper is later crowned world champion that year, Post adjusts the contract. ‘That was what we agreed upon during the contract negotiations and Post kept his word.’ The farmer’s son will earn 80,000 guilders at Raleigh in 1976; as a base salary, mind you.

When the composition of the teams for the Tour of the Netherlands - the final preparation race for the World Championships - is discussed, Frisol boss De Vries intervenes in the policy of team manager Libregts. He orders that an A-team must be built around Fedor den Hertog and that Kuiper, De Cauwer, and the others must operate in the B-team. Hennie barely pays attention to this demotion. ‘I was only focused on the World Championships.’ De Cauwer sees it as a humiliation, but he doesn’t mourn over it. He is used to working from an underdog position. The World Championships are Hennie’s main goal, so he trains every evening after the stage in the Tour of the Netherlands together with José. In the weeks leading up to the championship, the duo goes on training rides of up to 300 kilometers, rain or shine.

De Cauwer, who knows in advance that he will never be included in the incredibly strong Belgian team, fully adapts to the grueling training program of the team leader. After all, don’t they have a sort of partnership together? Then they must work together for it. José handles tactics and strategy; Hennie delivers results on the bike. The Tukker, who has a bigger engine than the Fleming, pushes his buddy to his limits. ‘At that time, I didn’t realize it. I didn’t feel José’s pain, but he did everything for me, pushed himself beyond his limits in training because he knew that intense training was good for me. That was our friendship and relationship during that period and it has remained so to this day.’ The duo Kuiper-De Cauwer becomes a unity. The cyclist-José dedicates himself one hundred percent to serving his team leader. The fact that they are of equal height works out well. In case of mishaps, Hennie always has a spare bike in the peloton during grand tours and classics: De Cauwer’s bike. It goes so far that De Cauwer adjusts the handlebars, saddle, and cleats exactly like Kuiper’s. Hennie shouldn’t feel any difference if he has to switch bikes.

In 1975, Hennie Kuiper is in his third professional season. He has already been through a lot, has experience, and has shown what he is capable of. But a battle for the world title is a whole different ball game, especially because Yvoir is the setting where the Belgian elite - led by Eddy Merckx, Roger De Vlaeminck, and Freddy Maertens - are towering favorites in front of their home crowd. The Dutch delegation to the World Championships is unprecedentedly successful in the days leading up to the professional title fight. Roy Schuiten (pursuit), Gaby Minneboo (amateur stayers), André Gevers (amateurs on the road), Keetie van Oosten-Hage (women’s pursuit), and Tineke Fopma (women’s road) all win a world title. But the climax, the battle for the global title among professionals, is yet to come. And all of Belgium is convinced that a compatriot will be crowned champion on that Sunday.

Montreal

The foundation for Hennie Kuiper’s world title in 1975 lies in the 1974 World Championships. Kuiper had already realized a year earlier, in 1973, that such a major championship suited him well. In the final of that World Championships, held on the Montjuich circuit near Barcelona, Gerben Karstens clings to Hennie Kuiper in the finale.

“Cramp,” he says. Karstens often pulls these kinds of pranks and Kuiper responds irritably with, “Get lost.” When he sees that ‘de Karst’ is not acting, that this renowned rider is truly at the end of his strength and he himself feels no pain, Hennie realizes that he can play a role in such a title fight. He is determined to make the next global title fight one of the main goals of his 1974 cycling agenda.

The 1974 World Championships are held in Montreal, Canada. Hennie has studied the profile of the course. It is tough and grueling, a task that suits him perfectly. He prepares conscientiously. The KNWU (Royal Dutch Cycling Union) has determined in advance that all selected riders must travel together eight days before the race day. This is a problem for Hennie because his sponsor, Robert Kahl, demands that the entire Rokado team start in the Grand Prix of Dortmund the day after the KNWU’s planned departure. Those who do not come can forget about their salary for the rest of the year. Hennie has no choice.

Hennie Kuiper has no choice and informs the union bosses that he will travel to Canada on his own. In Dortmund, he shows that he is in top form. On the challenging course, he beats Joseph Bruyère in the final, Eddy Merckx’s first lieutenant. After the race, Hennie travels to Frankfurt, stays overnight there, and then pays for a flight ticket to Montreal out of his own pocket. When he arrives in Canada, nobody from the union is there to meet him. But a hostess from the organization ensures that he ends up at the accommodation of the Dutch team. There awaits him a great disappointment. When he reports in, union director Harry Meuwese asks him what on earth he is doing there. “Cycling, of course.” But he is not allowed to cycle at all because he did not follow the rules. And the rules stipulate that he is obliged to travel with the team. The union officials do not care that in that case he would not have received any salary from his sponsor. No, the team has already been selected. Jos Schipper takes Kuiper’s place. When Kuiper promises Schipper a thousand guilders to give up his spot, Schipper hesitates for a moment, but Schipper’s sponsor prohibits him from accepting the offer. “And I can understand that as well.”

Hennie Kuiper comes first in Hoogerheide, ahead of Bert Pronk and Joop Zoetemelk. The Dutch champion's jersey will go to the Tour de France.

After the Dutch National Championships of 1975 in Hoogerheide, Hennie Kuiper freshens up among the crowd. On the far left, half of the caregiver Rudy Bergmans is visible, on the far right, half of Hennie's wife Ine.

With a satisfied look in his eyes, Hennie Kuiper unstraps his helmet. KRO's Bep van Houdt has the microphone ready to ask the new Dutch champion the first questions.

Desire-Believe-Act

And so the Dutch professionals who start on Sunday go without the man who has prepared like no other. Hennie is inconsolable. He strolls along the course and settles down all alone in the vicinity of the university building. Kuiper can’t stand anyone around him. ‘I wanted to process the grief and disappointment on my own.’ The championship on the extremely selective course is one big attrition battle. Only the strongest remain standing in this grueling fight. Eddy Merckx - who else - is honored as world champion among the professional cyclists for the third time in his career. He remains ahead of the ‘eternal second’ Raymond Poulidor. Two Dutch riders finish the race. In the back of the pack, to be clear: Tino Tabak finishes as number fourteen and Gerben Karstens as number fifteen out of the eighteen riders who complete the race. Kuiper watches it gritting his teeth. With him included, the result would have been different… Deep inside him, it boils. He seeks revenge and has a year to recharge. He thinks of his motto: Desire-Believe-Act. In this case: the Desire to play a leading role at the World Championships next year, the Belief that he is capable of it, and the Act - delivering a top performance - on race day itself. Those three elements, Desire-Believe-Act, were already at the core of his successful pursuit of the Olympic title in 1972.

The podium of the Dutch National Championship 1975 in Hoogerheide with from left to right: Bert Pronk, Hennie Kuiper and Joop Zoetemelk

Breed laughing in his national champion jersey, Hennie Kuiper takes a tour. It is certainly not a commercial celebration, although the hood of the DAF 33 is decorated with the text 'Costa Brava'

In the cycling-crazy Spain, fans hang on the fences to catch a glimpse of stage winner Hennie Kuiper among the promotional girls.

Great success for Hennie Kuiper in the 1975 Vuelta a España. On the penultimate day, he achieves stage victory in Miranda de Ebro as the only Dutchman that year.

The Frisol team at the table in Charleroi at the start of the 1975 Tour de France. Left at the table, from front to back: sponsor Nico de Vries (with pipe!), Theo Smit, Gerard Kamper, Ben Koken, José De Cauwer and Fedor den Hertog. Right at the table from front to back: team manager Piet Libregts, Cees Priem, Hennie Kuiper, Henk Prinsen, Australian Don Allan and Portuguese Fernando Mendes

On June 26, 1975, Hennie Kuiper - tongue out of his mouth - starts the prologue of the Tour de France with great concentration. The cameraman on the right is struggling to capture Hennie well in his shot. Francesco Moser wins the race against the clock over 6.2 kilometers. Hennie finishes very commendably in tenth place.

Jan Janssen and the coalition

Jan Janssen is the coach of the Dutch team for the World Championships in 1975, a role that he himself says doesn’t mean much. The federation asked him to take on this role, and he accepted, also because there isn’t much work involved. He knows Hennie and his wife Ine well. He is practically their neighbor in Putte, near the Belgian border. A few days before the race day, Janssen gathers all the selected riders at his home in Putte. There is a jovial atmosphere on the eve of the title fight. Jan Janssen is thrown fully clothed into his own swimming pool. They depart from Janssen’s villa, ‘Mon Repos,’ by bike to Namur, where the Dutch team has a hotel. Janssen knows from experience that the briefing on the eve of the World Championships is crucial. When riders, who compete against each other all year in different sponsored teams, can come to an agreement to join forces for that one day, they can enter the battle. Without a coalition, you are hopeless. The briefing goes smoothly. Joop Zoetemelk is the main candidate, but Gerrie Knetemann and Hennie Kuiper also have protected status. If one of these three gets into a promising position, not only will the rest of the team support them, but also the other protected riders will defend that chance. There is a prize pool available in case a Dutch rider becomes world champion, to be divided among those who have actually contributed. There are fifteen thousand guilders in the pot; it is expected that the winner will increase that amount by another twenty-five thousand guilders. Altogether enough to unite the team as one.

But what about the competition? Everyone is convinced that the danger mainly comes from the Belgians. They are the big stars, and they are also riding in front of their home crowd. First and foremost is Eddy Merckx, who has something to prove. In July, he was defeated for the first time in his career in the Tour de France. In the stage to Pra-Loup, Frenchman Bernard Thévenet took the yellow jersey from him. As it will later be revealed, he will never conquer that coveted jersey again. Merckx is highly motivated to show that he is still the boss in cycling through a world title. Additionally, there are at least three other contenders: Frans Verbeeck, who has won many one-day races, Freddy Maertens, who has an impressive sprint and finds the course in Yvoir just manageable enough, but above all there is Roger De Vlaeminck, who is having a superb season

The super season of Roger De Vlaeminck

De Vlaeminck starts the season as usual with cyclocross, a branch of cycling that Hennie also practices, albeit at a much lower level. Kuiper is crowned national champion among the professionals twice in a field dominated by amateurs. De Vlaeminck is accompanied by physiotherapist Georges Debbaut, who once made a name for himself as a footballer. Debbaut introduces new training methods, telling the riders that they should already lay the foundation for the new season during the winter months. Until the 1960s, many cyclists still believe that you should save your strength in winter to be able to perform strongly again from the end of February. Debbaut, who takes Walter Godefroot and Roger De Vlaeminck under his wing, proves the opposite. In the forests around Lembeek and on the beach at the coast, he imposes a strict training regime on his athletes, with the bike usually untouched. He is the mental and physical advisor of De Vlaeminck.

The start of De Vlaeminck’s cycling year 1975 is overwhelming. The slender Belgian wins both the national and world cyclocross titles. On the road, he impresses equally. For the fourth consecutive time, he triumphs in the Tirreno-Adriatico, where he achieves three stage victories, including the final time trial. With Willy De Geest as his ideal helper, he gets flu after the Tirreno, but when he recovers, he signs up for Paris-Roubaix, where he triumphs for the third time; this time ahead of Merckx, André Dierickx, and Marc Demeyer. Afterwards, he beats the competition in the Zürich championship. De Vlaeminck continues his winning streak in the Giro d’Italia (seven stage wins, points classification, and combination - the jersey for the rider with the best overall score in points and mountain classification.) In the Tour de Suisse, he wears the leader’s jersey from start to finish. Compare Hennie Kuiper’s performance list here on the eve of the 1975 World Championships and you realize that Dutch champion holds a subordinate position in the bookmakers’ odds.

Ezelstamp

The Belgian road championship turns out to be a failure for De Vlaeminck. He finds the course subpar. Although he still finishes fourth, he considers it beneath his dignity. After the national title race, only one race matters to him: the World Championship in Yvoir in front of his home crowd. He maintains his form in smaller races and criteriums. Ten victories prove that his condition is still very good. When the Belgian Cycling Federation announces the selection for the World Championship, De Vlaeminck reacts furiously. Merckx is assigned three teammates: Jos De Schoenmaeker, Ward Janssens, and Joseph Bruyère. Freddy Maertens is supported by Michel Pollentier. But the man who can present an unparalleled list of important victories that season, De Vlaeminck, is left without support. There is no place for his loyal lieutenant, Willy De Geest.

De Vlaeminck is beside himself. He wonders if he should still wear the Belgian jersey at the World Championship. ‘They have given me the donkey stamp,’ he fumes. ‘This is not a team of eleven riders. This is one of ten plus one separate rider. It would be best if the officials let me ride in a white jersey, so the public can see that I am the outcast of the team.’ De Vlaeminck chooses his own path. He turns to his Italian sponsor and builds a strong support team around him to be optimally prepared for the race. He secures the assistance of doctor Piero Modesti, caretaker Silvano Dago, and two mechanics. The always nervous De Vlaeminck is molded into a confident athlete.

And yet… in Yvoir, things go wrong for Roger, terribly wrong. But not for Hennie! The basis for his defeat partly lies with De Vlaeminck himself. On the eve of the World Championship, a meeting is also held by the Belgian professionals. During that team meeting, led by Lomme Driessens – a man of many words who always considers the riders’ successes as his own – De Vlaeminck tries to be funny. Driessens starts the meeting by highlighting the quality and quantity of the team. The outgoing world champion, in this case Eddy Merckx, always has automatic entry. This means Belgium can start with one more rider. ‘We are eleven,’ says Driessens. But then De Vlaeminck jokingly calls out in the room where the selection is gathered: ‘Ho, ho, ho. We are ten and a half.’

The ‘half’ Lucien

That ‘half’ refers to the smallest of the group, the Belgian climber Lucien Van Impe. There is laughter: the always friendly, small Lucien as the target of jokes. José De Cauwer recognizes that. With his small stature, he has often been the victim of ‘jokers’ who try to be funny at the expense of others. ‘If you want to motivate your opponent, make sure to provoke him,’ says De Cauwer. De Cauwer later experiences something similar at the Raleigh team. There, the shy Hennie is occasionally teased by outspoken Westerners about his speech impediment. ‘Those teasing,’ De Cauwer knows, ‘nestle in your head, crawl under your skin. That teasing makes you angry. And if you can’t retaliate with words, you do it on the bike.’ Sometimes - like Hennie occasionally - by outperforming the competition, another time - like in the case of Lucien Van Impe - by refusing to give your heart and soul in the pursuit of a fugitive at a World Championship. This happens when De Vlaeminck asks him to help bring back the escaped Kuiper during the World Championship. Van Impe initially refuses. After all, he’s just a half? De Cauwer knows that it can be fatal when you belittle someone. When you kick a dog, that animal remembers it three years later. It’s no different with people. ‘If you have hurt someone, you will always be paid back for it later.’

Hennie Kuiper shows off the national champion jersey in the Tour de France. It is Monday, July 14, the French national holiday, which will get an extra festive touch thanks to Bernard Thévenet's stage victory. Hennie Kuiper struggles alone on the slopes of the Col d'Izoard

After the Tour, the criterium circuit also wants to marvel at the Dutch champion. Although Hennie Kuiper is trailing, the audience almost comes through the fences during the Acht van Chaam.

Anti-Joop

On the eve of the World Championships, the attitude of Belgian cycling fans towards the Dutch - or rather towards Joop Zoetemelk - is distinctly hostile. Joop, who in 1970 is widely praised after finishing second in his first Tour de France as a debutant following Eddy Merckx, is the hero. A year later, he repeats that performance, once again standing next to the Belgian on the podium, but then the cheers, especially in Belgium, fall silent. The cycling public wants to see a battle, hopes for an opponent who truly challenges Merckx, but Joop is not an attacker: he clings on. It is not in his nature to engage in a fight with a rider who possesses better qualities than himself; in fact, a fight with a rider like the world has never seen before. Zoetemelk knows he will lose that battle. Clinging on is already difficult enough.

In the Belgian press, Joop is portrayed as a coward. Jokes circulate such as: ‘Why does Zoetemelk look so pale?’ Answer: ‘Because he always rides in Merckx’s shadow.’ No, Joop is certainly not popular in Belgium. He is called a ‘wheel sucker’. Milk bottles hang in the trees along the course, symbolizing Joop’s white skin and surname. Joop is mocked. Apparently, the Belgians have forgotten how much Eddy Merckx’s throne wobbles when Joop Zoetemelk sweeps all major stage races in the spring of 1974: Paris-Nice, the Catalan Week, and the Tour of Romandy. No one - not even Eddy-the-Great - can stand in his shadow. A disastrous and almost fatal crash in the Midi Libre puts an end to all of Joop Zoetemelk’s illusions. Merckx wins his fifth and final Tour de France that year. It is a Tour victory with the least shine. ‘If’ Joop hadn’t fallen… But ‘if’ doesn’t count in sports. Hennie Kuiper: ‘Joop missed at least two Tour victories because of that fall.’ And Hennie is not the only one who thinks that way. All of this does not matter to the fanatic part of Belgian cycling fans as they line the World Championships course. The Dutch team is escorted in the morning by a group of ‘Zwaantjes’, motorized members of the Belgian Gendarmerie, who are tasked with preventing hot-heads from attacking Dutch riders in general and Zoetemelk in particular. The coach on duty, Jan Janssen, also faces anti-orange sentiment. When he arrives at the start with his team car, he is approached by a motorized gendarme. Mr. Janssen should really take it easy on this day. He must behave ‘nicely’, do what everyone else does; so stay in line. The gendarme seems to be infected by the anti-Zoetemelk sentiment of the public and Jan is seen as the coach of the hated Joop.

And what happens during the race? Through the radio, Janssen receives word: flat tire for Gerard Vianen. The coach drives towards the peloton to fix the issue but then encounters the ‘Zwaantje’ who had warned him before the start. Janssen tries to pass on the left side of the gendarme, who also veers left. When he tries on the right side, the gendarme blocks his way again. Jan reacts angrily and rams into the motor from behind. The gendarme ends up in the ditch with his motor. But Jan manages to reach the peloton, assist Vianen, and take his place back in line with team cars behind the peloton.

What Janssen did on the way was certainly not ideal. The gendarme, who was knocked down, went straight to his superiors in anger. That goes against all rules: hitting a motor officer.

That Janssen gets away with a ‘serious warning’ is thanks to Piet van der Molen, chairman of KNWU and former police commissioner. Van der Molen has to talk his way out of it but manages it: Janssen is spared. Without Van der Molen, Holland’s first Tour winner could have faced at least two weeks of imprisonment. Joop Zoetemelk, the target of anti-sentiment in Yvoir, still remembers being verbally attacked on his way to start and during the race. Countless times he heard accusations: ‘wheel sucker’, ‘profiteer.’ Many supporters have pacifiers in their mouths symbolizing sucking on Merckx’s wheel. Tomatoes are thrown towards him but none hit their mark. People are agitated, especially by the media. Joop realizes he risks being pushed off the road if he attacks. Zoetemelk: ‘Yet I never felt fear.’

There may be 102 riders registered for the road race of the 1975 UCI Road World Championships in Yvoir, Belgium, but for most fans, the race revolves around just one man: Eddy Merckx...