A turbulent spring

Raleigh starts the 1977 cycling season as usual: with the Tour of Andalusia. Just like the year before, Hennie finishes in second place. But there is a big difference with the second place of 1976. Because in that year, Gerrie Knetemann is the victor; in the new season, Didi Thurau precedes him. The German wins - except for the prologue and the final stage - everything in Andalusia. Post is strengthened in his opinion: Thurau must be his man; unlike his current team leader Hennie Kuiper, Thurau is a rider with charisma and thanks to a razor-sharp sprint also a winner.

Hennie has a mediocre early season. One result stands out: his third place in the Amstel Gold Race. That is - on paper - a good result, but team boss Peter Post sees it as one of the bitterest defeats of the Raleigh period. This has everything to do with the exciting finale of this classic race. Three Dutch (what a luxury…) riders color that finale. Two of them wear the Raleigh jersey: Gerrie Knetemann and Hennie Kuiper. The third is their former teammate Jan Raas. The Zealander left angrily at Post at the end of last year. He did not get the position nor the financial reward he felt he deserved. Raas switched to Piet Libregts’ Frisol team and to Post’s annoyance won the prestigious St. Joseph Classic, Milan-Sanremo in that sponsor’s jersey.

When he finds himself with two Raleigh riders in the finale, Post expects a victory from his men. Kuiper may be called an ‘iron’ as a sprinter and Knetemann may have to give way to Raas in pure speed; in the kilometers remaining until the finish, those two seasoned riders should be man enough to outsmart the lonely Zealander. It must be said: the duo gives it their all. They attack one after another. ‘Kneet’ puts everything into a blistering acceleration. ‘Kuip’, not naturally explosive, goes as hard as possible. Knetemann tries again, Kuiper again, and so on, and so on. Raas has to deal with fifteen attacks in total: six from Hennie, nine from Gerrie. But Jan Raas shows just as many times that he is the absolute king of classics. Raas is more determined than ever to beat these two Raleigh men. It is his ultimate revenge on the team manager who did not have enough faith in him. And he succeeds. To the great anger of Post, who still lacks a major victory that spring. There is criticism from outside. Post focuses too much on Thurau, who has not yet lived up to high expectations. But Post dismisses that criticism. He points to the top ten finishes that the German achieves after the Gold Race: eighth in Paris-Roubaix, third in Liège-Bastogne-Liège. Post says: ‘A rider like Didi must be given the most chance. I have always believed in his class. And even though he hasn’t won his big race yet: I will continue to build on him.’

Henninger Tower

Post and Thurau are mainly focused on winning the German classic, Rund um den Henninger Turm, which, as tradition in those years dictates, is held on May 1st in Frankfurt. The Raleighs coordinate the race around Thurau, but Gerrie Knetemann disregards team orders. He launches a devastating attack 38 kilometers before the finish line and stays out of reach of the chasers. Thurau feels trapped. He is not allowed to chase after a teammate. After a solo effort, he is left with only second place. The German is deeply disappointed and makes it clear.

That same evening, Didi is approached by a representative of the IJsboerke team. Not long after, he secretly signs a multi-year contract with the Belgian sponsor. He brings Bert Pronk as a domestique and Ruud Bakker as a soigneur. The following year, Raleigh loses that trio.

Post, who has an extensive network of informants, is informed before the Tour of Thurau’s imminent departure. He keeps the information confidential, hoping to first score with the charismatic German in the Tour, as his trust in Thurau’s abilities remains unbroken.

In the Amstel Gold Race of 1977, the Raleigh's of Peter Post once again demonstrate their dominance. Hennie Kuiper climbs the Keutenberg ahead of Eddy Merckx

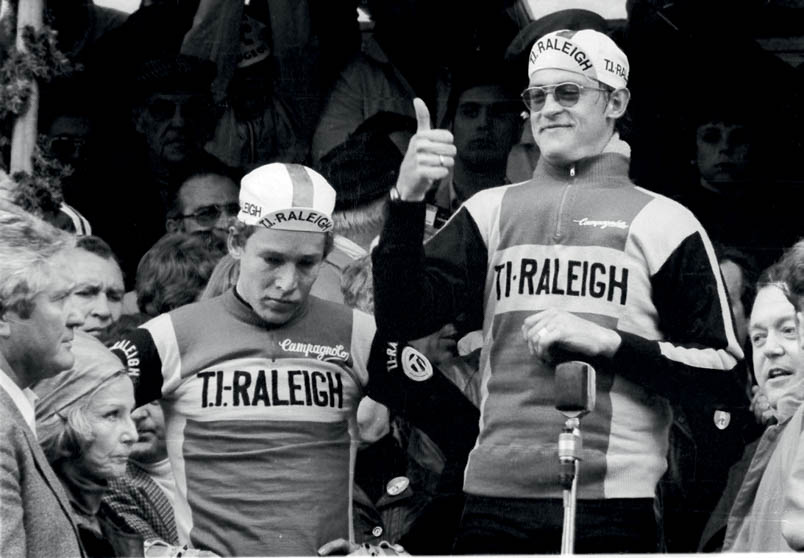

In the final of the Gold Race, Post has two aces up his sleeve: Hennie Kuiper and Gerrie Knetemann (on the right). However, the most dangerous man of the trio is riding on the left side of the road and wearing the Frisol jersey: Jan Raas

Knetemann and Kuiper try to break Raas in the Gold Race - taking turns - by attacking, and Raas keeps closing the gap each time. That's what Raas does: he is very keen on winning the Amstel.

The tension rises in the final kilometers of the Amstel Gold Race. Raas tries to keep the motorcyclist of photographer Tonny Strouken at a safe distance with hand gestures.

Peter Post is furious when Jan Raas easily beats Knetemann (left) and Kuiper in the sprint of the Amstel Gold Race

The podium photo in Frankfurt from Rund um den Henninger Turm speaks volumes about the dynamics within the TI-Raleigh team. Gerrie Knetemann wins after a solo effort. Didi Thurau's face looks like thunder. That same evening, he secretly signs a contract with IJsboerke.

The Stimul affair

Apart from his third place in the Gold Race, Hennie cannot provide a list of achievements that would impress anyone that spring. Two factors play a role in this: he is struck by a persistent flu and… Kuipers’ name is mentioned in a doping scandal. Doping is the main issue in cycling in the spring of 1977. In the laboratories where athletes’ urine is analyzed, lab technicians had found a substance years earlier that they could not identify. It was suspicious, but they couldn’t pinpoint exactly what it was. Professor Dr. Michel Debackere, a pharmacologist-toxicologist, is the director of the veterinary faculty at the University of Ghent. In his laboratory, urine samples from top athletes are tested for the use of prohibited substances.

Debackere has already built up a certain reputation. In 1974, he managed to prove the use of Ritalin and Lidepran, two popular doping preparations in the peloton. He kept his discovery quiet until the spring races began. In the Tour of Flanders, Walter Godefroot was the first to be caught. He would later be caught again for using prohibited substances in the Fleche Wallonne. This led to a four-month suspension for him. It turned out to be the precursor to a long list of those caught. Dutchman Theo van der Leeuw (Amstel Gold Race), Belgians Ronny De Witte and Wilfried David, Frenchman Raymond Delisle (Liege-Bastogne-Liege), and Belgians Eric Leman, Freddy Maertens, and Joseph Bruyère (Tour of Belgium). Belgian cycling fans reacted angrily. They considered it a disgrace that the big stars were being exposed like this. ‘You should not be forgiven on your deathbed for all that you have done,’ wrote a supporter who seemed to have lost his way. But parents of a young rider expressed in a note: ‘Keep going, professor. Because doping is a serious issue. We see enough of it.’

That was in 1974. But meanwhile, the Ghent laboratory continued its search for another preparation that - as the tests showed - was also frequently used. In 1977, they finally succeeded. ‘We now have a foolproof test with which we can scientifically prove the use of Stimul,’ said Debackere. ‘And we will start in the spring races, just like in 1974.’ Stimul is a product from the amphetamine group and according to Debackere, it can harm health. Until 1974, laboratories would often inform athletes when they could detect certain products in their urine, like: ‘Be careful, stop using that product because we can detect it.’ However, Debackere works in secret and also prohibits his staff from informing the cycling peloton in 1977.

Astonishing effect

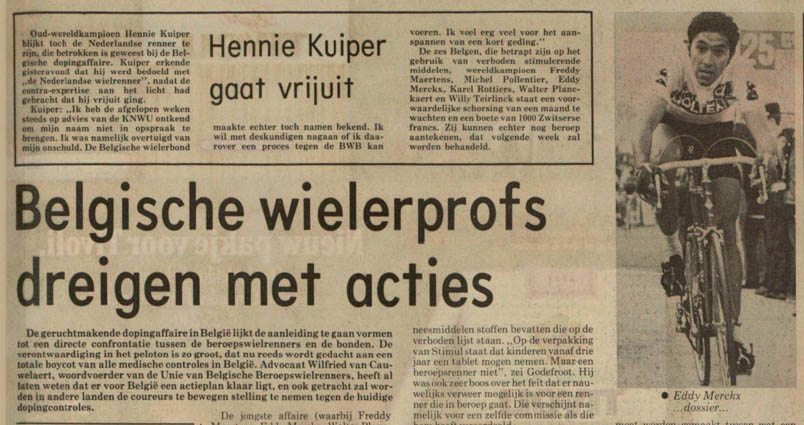

The effect is astonishing. When the results of doping controls in races like the Tour of Flanders, the Fleche Wallonne, and the Tour of Belgium are revealed, it turns out that a large number of riders have used Stimul. The laboratory in Ghent waited until all the classics were over before announcing the first positive cases. The ‘catch’ is - to the anger of the peloton - significant. It’s not the least of riders who are being crucified: Eddy Merckx, Freddy Maertens (three times respectively in the Tour of Flanders, the Fleche Wallonne, and the Tour of Belgium), Willy Teirlinck, Guy Sibille, Walter Planckaert, Michel Pollentier, Karel Rottiers, and yes, even Hennie Kuiper.

It is the first and as later turns out, the only time in his career that Hennie’s name is associated with doping use. He is completely shocked when he receives a letter from the Royal Dutch Cycling Union stating that he has tested positive in a control. The news - ‘Hennie Kuiper is positive’ - reaches the outside world. TV reporter Fred Racké shows up with a camera crew at a race in Zeeland. Hennie is completely shaken when a microphone is shoved in his face. The camera is rolling, but Hennie stutters, worse than ever before. For a part of the audience, he falls from his pedestal. Hennie? Him too?

Kuiper claims to be innocent. He requests a counter-analysis, hoping that the second urine sample will prove his innocence. The Raleigh team leader enlists a reputable expert at the time to assist him in the re-examination: Professor Jacques van Rossum. And… the counter-analysis is negative. Hennie Kuiper is cleared of any wrongdoing. The only one in the list.

Nevertheless, the incident has a strong mental impact. Add to that the flu, and it’s clear that Hennie remains far from his optimal form that spring. However, as the season progresses, he starts feeling better and better. His physical (the aftermath of the flu) and mental (the issues surrounding the doping control) condition improves. In the Tour of Switzerland, he is not yet at the level of the previous year, but in the stage to Bellinzona, he shows that he is back on track. He joins an escape with none other than his great idol, Eddy Merckx. In the final sprint, Kuiper is obviously no match, but it’s still a second place that counts. He looks ahead again and is determined to at least reach the podium in the upcoming Tour de France.

The newspaper headline leaves nothing to be desired when his name is cleared of alleged doping. 'Kuiper is acquitted', reads the headline in the Nieuwsblad van het Noorden