Hennie’s Day of Vengeance

On the evening before the World Championships, Hennie calls his buddy José and asks him what he expects. ‘The way you’re riding now, you should be able to finish in the top ten.’ Hennie has his response ready immediately. ‘Top ten? But then I can also win.’

Oops.

Kuiper has those days when he manages to push his limits towards the impossible. August 31, 1975 is one of those days. For Hennie, it is the Day of Vengeance, just like it was on September 7, 1972. On that fateful September day - during the Olympics - he takes revenge on his coach and selectors, who had refused to select him for the World Championships team in the past years. He damn well wants to show what he is capable of. And he shows it on the Olympic course in Munich.

Now, three years later, he has another score to settle with the cycling federation, which unjustly prevented him from starting on the grueling World Championships course in Montreal a year earlier, a course that seemed tailor-made for him. He suppresses his pain but nurtures his anger and works tirelessly for a year towards his revenge. Hennie does not want to gradually approach the final. Already in the first lap, he is part of a four-man strong breakaway group that does not last long. He can bide his time when teammate Karstens is ahead for a long time, but when the decisive breakaway group forms, he is present at the front. Three Belgians (Merckx, De Vlaeminck, and Van Impe), three Frenchmen (Thévenet, Jean-Pierre Danguillaume, and Régis Ovion), and three Dutchmen (Kuiper, Zoetemelk, and Gerrie Knetemann) form the major power blocs within the group; Italian Francesco Moser is the dangerous outsider. Spaniard Pedro Torres completes the eleven escapees.

Michel Pollentier sets a blistering pace at the front three laps before the end. In his wheel: Hennie Kuiper. The group is significantly reduced. Pollentier and Kuiper have a slight lead at the top. Pollentier drops back from the front; Hennie pushes on and gradually builds a lead. Joop Zoetemelk watches it all unfold. ‘I thought: let Kuiper make the move. You never know how it will end up. If they catch Hennie, there are opportunities for De Kneet and for me.’ In the group behind him, they look at each other. There is no slacking off; the pace remains high, but everyone is watching the favorites, the Belgians. Van Impe rides his own race, the French coordinate their efforts around De Vlaeminck and Merckx, and the remaining Dutch riders in the breakaway group do nothing but counter all counterattacks. There are plenty of counterattacks: from Merckx, from De Vlaeminck, and from Moser. Each time either Knetemann or Zoetemelk latches onto the wheel of whoever tries to chase down Kuiper. Each time, those attacks raise the tempo again, but it stalls once more as soon as the attacker sees Zoetemelk or Knetemann hanging on.

There is no organized chase behind Kuiper. Merckx does not want to hand over the world title to De Vlaeminck and vice versa. Roger De Vlaeminck is desperate. Isn’t this supposed to be his World Championships? Doesn’t he deserve more than anyone else to claim the title? There is only one rider who has what it takes to help him get that rainbow jersey: Eddy Merckx. But the defending champion wants to go for his own chance. The other Belgian in the breakaway group, Lucien Van Impe, is so angry about being humiliated on the eve of the World Championships that initially he refuses to lend a hand to Roger.

Then help arrives. The three Frenchmen in the breakaway group - Thévenet, Danguillaume, and Ovion - realize that they are hopeless in this title fight. Their own attempts to break away will be thwarted by both the Dutch and Belgian riders, especially by De Vlaeminck. But you are a professional cyclist or you are not: you still want to return from such a World Championships with a filled wallet.

There is business to be done because doesn’t De Vlaeminck really want to become champion? Doesn’t he need help in his pursuit of Kuiper? And that help is offered to him as photographer Tonny Strouken hears from Bernard Thévenet the next day. You scratch my back; I scratch yours. And for a lot of scratching comes a lot of money.

The exact amounts remain shrouded in mystery. Roger finds it substantial but not insurmountable. However, there is another problem. Because there is an agreement that if one of their men becomes champion, then Belgian teammates will be paid as well. So at least an equal bonus will have to be paid out to other Belgians who have not acted as teammates at all. Altogether this forms an unimaginably large sum. Furthermore, De Vlaeminck cannot bear the thought of having to pay Merckx (finishing as number 8), Van Impe (9), Verbeeck (13), Dierickx (20), and Maertens (21) for his rainbow jersey while none of them lifted a finger to help him. So he tries himself but each time finds Knetemann or Zoetemelk on his wheel smothering every individual attempt and thus excellently shielding Kuiper’s escape.

The Dutch riders act as a team according to an agreement made the night before. Zoetemelk and Knetemann naturally would prefer to win themselves but they prefer Kuiper winning over Merckx or De Vlaeminck. Moreover, they reason: it’s good for Dutch cycling. At the beginning of his escape, Hennie does not think about winning at all. ‘I wanted to make the race hard.’ He still has 28 kilometers ahead when he leaves behind the rest of the breakaway group. Kuiper climbs at high speed in his distinctive angular style. They are certainly not idle behind him. Merckx, Moser, De Vlaeminck, Danguillaume; all hope in one mighty rush they can close in on Kuiper’s gap. De Vlaeminck comes closest but fails to drop Joop Zoetemelk from his wheel. Hennie holds on until crossing the finish line. He can hardly believe it himself. And Belgian supporters do not want to believe it either. There is a deathly silence at the finish line. Belgium mourns. De Vlaeminck, second place in the title fight, crosses with tears in his eyes over the finish line. De Vlaeminck and Moser express their displeasure after that someone with such a modest palmares will wear the rainbow jersey for a year.

Pilgrimage

The entire cycling-loving Netherlands follows the championship via Dutch or Flemish television. Also at the Kuiper family, almost everyone is glued to the screen. But father Gerard and mother Johanna are unaware of what is happening. At the moment their son triumphantly crosses the finish line in Yvoir, they are attending a service in the church in Kevelaer. This service marks the end of the annual pilgrimage to Kevelaer, which Gerard and Johanna traditionally participate in.

That son Hennie is cycling in the World Championships is great, but that is no reason to skip the pilgrimage. When at the end of the day the bus with pilgrims returns to Denekamp, the Kuiper parents are informed. ‘Have you heard? Hennie is world champion.’ Only when everyone, including the priest, confirms the news, do the parents believe it. ‘Oh, really…?’

Of course, the parents are extremely proud of son Hennie. But mother emphasizes that all her children are equal to her. ‘If you have received a gift from Our Lord, you must also use it. World champion? Wonderful, but I hope he doesn’t think he’s now greater than Our Lord. I have always taught my children not to forget to pray. Mr. Priest sometimes says: “Your son has remained so humble.” Then I answer: he got that from his father and me.’

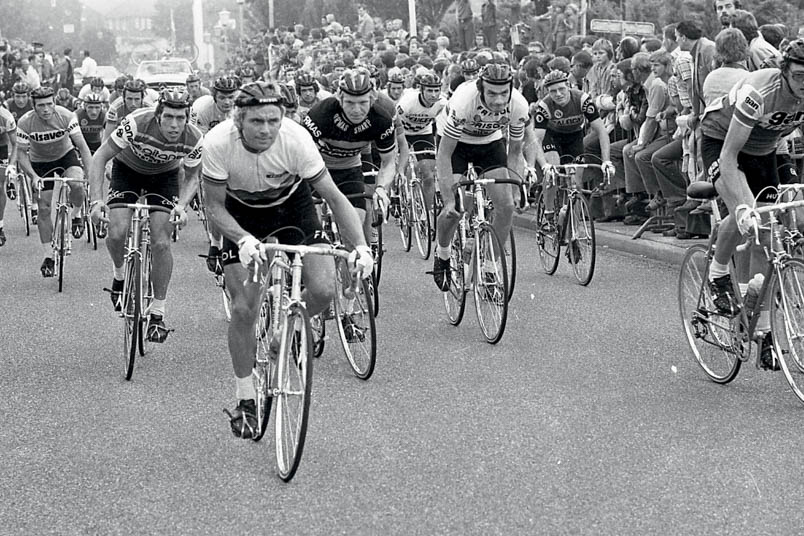

The big names of cycling come together at the 1975 World Championships. From left to right: the Spaniard Domingo Perurena, Freddy Maertens, Francesco Moser, the Italian Roberto Poggliali, Hennie Kuiper and Roger De Vlaeminck

Hennie Kuiper passes his wife Ine (with glasses, immediately to the left behind Kuiper) during the World Championship road race. The group also includes Belgian Willy Teirlinck, Frenchman Yves Hézard, and Italian Giovanni Cavalcanti. Hennie is already flying in the first lap.

Hennie Kuiper comes across the finish line in Yvoir with his arm outstretched. But the predominantly Belgian spectators do not share in the joy of the new world champion.

The disappointment does not drip, but washes off the World Championship podium in Yvoir. While world champion Hennie Kuiper listens to the Wilhelmus, Roger De Vlaeminck (left) has his gaze fixed on a point beyond infinity and apparently a completely different scenario is still playing through the mind of Jean-Pierre Danguillaume (right)

Hennie Kuiper is being dressed in the rainbow jersey by Adriano Rodoni, the president of the International Cycling Union UCI

Amidst the meadows, on a podium by the road, the realization finally dawns on Hennie Kuiper in the form of a smile. Flowers, a gold medal, and the rainbow jersey: it's really true - world champion!

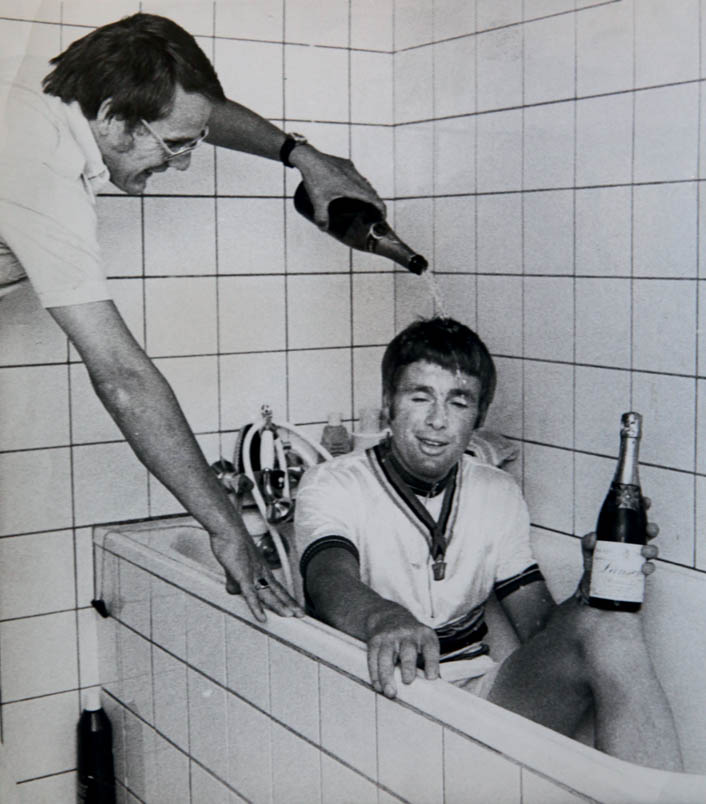

The world champion is taking a bath and national coach Jan Janssen is not stingy with the champagne

At the steps of the town hall of Ossendrecht, Hennie Kuiper is addressed by Mayor André van Gils (on the right) and cheered on by the local population. To the right of Kuiper, the head of his mother Johanna can just be seen. Next to her is VARA's Things of the Day reporter Frits Bom.

Upon returning home in Ossendrecht, Hennie and Ine Kuiper receive a musical tribute.

José and the cognac

José De Cauwer is in his hometown of Temse, sitting glued to the TV with his father, as his team leader is competing in his World Championship race. Between the two men sits a bottle of cognac. When José’s team leader triumphantly crosses the finish line, the bottle is almost empty. De Cauwer listens to the TV commentators’ remarks, of rival riders. The next day, he reads the reports in the Flemish newspapers, where the opinion quickly emerges: ‘Kuiper has only been able to hold on because Merckx and De Vlaeminck raced against each other in this championship.’ But José knows better: this title is not a gift. This title belongs to Hennie Kuiper. He has put in a beastly amount of work to get this far. And on that race day, he is the best. The very best.

The day after, De Cauwer tells the new champion that he does not yet realize what the new status entails. ‘It’s only just beginning now. In a year, when Hennie takes off the rainbow jersey and someone else wears that jersey, he will realize what it all meant. Then he will say with some amazement: am I the one who has been riding around with that jersey for a whole year?’ For Hennie, as José knows, ‘that is inconceivable.’

The Belgian media tear into Hennie Kuiper. They label him as the new Harm Ottenbros, the Dutch rider who sprinted for the title with Belgian Julien Stevens in 1969. Ottenbros is considered the biggest surprise at World Championships in the post-war period: a rider who in the eyes of many absolutely cannot claim the rainbow jersey. According to many Belgians, Hennie is equally unworthy of the title. You can’t provoke Kuiper more than by belittling him. He, Hennie Kuiper, not a worthy world champion? He will show them.

In Paris-Brussels in 1975, an autumn classic, a strong wind blows. The peloton breaks up into echelons and riding in crosswinds is not exactly Kuiper’s specialty. José De Cauwer also realizes this as he picks up Kuiper somewhere at the back of the field, directs him to his wheel, and acts as a windbreaker for kilometers for the freshly crowned world champion, navigating from one echelon to another. Eventually, De Cauwer neatly delivers his team leader to the first echelon, where alongside stars like Maertens, Merckx, and Verbeeck, teammate Cees Priem also resides. Hennie ultimately finishes as number seven and has succeeded in his mission. The new world champion has shown his jersey.

Flanders and Twente

Sponsor director De Vries, who initially denies that he wanted to get rid of Kuiper a few months ago, hopes to still benefit from the rainbow jersey publicity-wise for his transfer to the TI-Raleigh team of Post. He has a letter written to Hennie, requesting him to pay a little more attention to his clothing. Teammate José can understand that. Not that Kuiper’s clothing looks worn out, no, it’s all very decent and clean, but it’s clothing that hasn’t been in fashion for five to ten years. That doesn’t fit the stature of a world champion.

De Cauwer wears a dark brown, tailored leather jacket in those days. Underneath, a dark blue suit with a light blue shirt and a dark blue tie. All according to the fashion of those days. Hennie inspects his teammate and says, ‘I find that beautiful. Where did you get that?’ Well, here and there. ‘Then I’ll buy the same.’ José protests vehemently. They are both the same height and now they will be seen everywhere in the same clothing. The Belgian thinks that’s not acceptable. ‘Then we’ll be the duo Spik and Span.’ But Hennie sticks to his intention. Two, three years later, De Cauwer doesn’t find that leather jacket so perfect anymore. The garment has gone out of fashion a bit and he buys a new jacket. Not Hennie. Five years later, he’s still wearing the same jacket. After all, it’s not worn out yet? It’s the difference in culture between a Burgundian Belgian and a somewhat stiff Twente person, which - according to José - is perfectly fine.

De Cauwer had already noticed this cultural difference between Flanders and the Netherlands - or rather: between Flanders and Twente - during earlier visits. When tea or coffee is served in Flanders, there is a large platter on the table with all sorts of things. You take what you want and when the platter is empty, it gets refilled.

In Twente, it’s very different, José notices on his first visit. The cookie jar is opened briefly, you take one out, and before you know it, the lid is back on the jar. He remembers that after his first cookie, he personally opened the jar again and took out a second one. He still sees Hennie looking at him with a look that betrays both astonishment and disapproval. ‘What are you doing at my family’s?’ Well, that takes some getting used to. In Twente, you wait until it goes around again; in Flanders, you take as much as you want.

For a long time, De Cauwer believed that the Netherlands, even up to Tukkerland, was a land of oysters and mussels. He looked forward to it when he went there for the first time. After all, that seafood is massively imported from Zeeland. That thought turned out to be completely wrong. In Twente, he finds none of that: no mussels anywhere and not even one oyster.

When Hennie’s youngest brother Jos gets married in winter after the World Championships in Yvoir, José is among the guests. There is also a reporting team from the Belgian sports magazine Sport 70. This team includes Rik Van Looy, the absolute cycling emperor of the sixties. The day starts in Catholic Twente with a holy mass. De Cauwer and the Sport 70 team can’t believe their eyes when the world champion steps forward during the mass and sings the Ave Maria perfectly with brother Gerard. ‘Unthinkable for us,’ they say. But for Hennie, that’s just normal, as he had previously served as an altar boy at Frans’ wedding with Bennie.

After the mass, the bride and groom along with guests head to the reception hall. To the surprise of the Belgians, the hall empties around five o’clock. ‘What’s going on here?’ It turns out that the farming families have to go milk the cows. They return to the party around nine o’clock in the evening. They have a beer, then another one, and another one, and then another.

Just as the Belgians start rubbing their hands together thinking: now the party will really start, the hall empties again. By midnight, everyone has left. The next morning awaits farm work: milking needs to be done again. The party is over. In Flanders, they party until four or five in the morning.

Twente turns out to be a whole different world

During the evening tour of Ossendrecht, Hennie Kuiper shows the rainbow jersey to his fellow townspeople.

In a furniture store in Winterswijk, Hennie Kuiper happily signs autograph cards for the local youth

The first race of Hennie Kuiper in the rainbow jersey is the criterium on the Kollenberg in Sittard. Bennie Ceulen is in Kuiper's wheel. From left to right: Aad van den Hoek, Jan van Katwijk, Tino Tabak, Joop Zoetemelk, Bennie Ceulen, Bernard Thévenet, Hennie Kuiper, Don Allan, Jos Schipper, Henk Prinsen, Jacques Esclassan, Albert Hulzebosch, Bert Pronk and Gerrie Knetemann

Hennie Kuiper is a very talented cyclocross rider, who won the national title in the professional category in both 1974 and 1975. In 1976, he withdraws because he believes that winning the world title on the road creates other obligations. Purely for training purposes (he finishes thirteenth), Kuiper does participate in Oss in January of that year. Through cyclocross, Kuiper develops a skillful handling of the handlebars that proves particularly useful to him in Paris-Roubaix.