Tour 1976: joy and sorrow

Hennie Kuiper starts his second Tour de France with a wonderful feeling. He has shown that he is not always the rider of ‘just not quite’ as seen earlier in the Omloop Het Volk, in Paris-Nice, and in the Tour of Spain. After winning the Tour of Switzerland in the weekend before the Tour start, he even sees a chance to beat Joop Zoetemelk uphill in the battle for third place at the Dutch championship. Now even team boss Peter Post is starting to regain confidence in Kuiper’s abilities. Could it be that he will…

The leader of TI-Raleigh has conscientiously prepared for the world’s most important cycling event. In addition to the ambition to clearly show the rainbow jersey, he also brings the experience of one year of Tour cols. He gets briefed on the difficulty of the new mountains for him. But for Hennie, the importance of the stage to be ridden on Friday, July 9th stands above all. On that day, his parents celebrate their fortieth wedding anniversary. Their cycling son has a special gift in mind: a stage victory that he wants to dedicate to his father and mother. ‘That was above everything for me.’

The fairytale of Bornem

Hennie Kuiper is performing well in the first days of the Tour. On Monday, June 28, the caravan makes a detour to Belgium from Le Touquet. Freddy Maertens has already been wearing the yellow jersey for the fourth day. Apart from the prologue and the time trial in Le Touquet, the leader of Flandria is also too strong for the competition in the first stage to Angers. In his home country, he wants to continue his triumphal procession. And so, stage 4 - to Bornem - is marked in red in the road book. José De Cauwer knows every meter of the finale of that stage. He lives on the other side of the Scheldt. The finish line is drawn five kilometers from his house. And although the pace in the finale of that stage, despite the scorching heat, is high, Hennie asks De Cauwer to ride to the front of the group at about seventeen kilometers from the end. De Cauwer knows that the peloton must slow down momentarily for an attack to have a chance of success.

Swiss rider Eric Loder. He can’t expect any support from that side. Loder has only one task, to stick to the Dutchman’s wheel to give the peloton a chance to catch up and allow sprinter Maertens to demonstrate his supremacy in front of his own fans. Kuiper’s teammate, José, immediately starts blocking when his leader attacks. But the Flandria train of yellow jersey wearer Freddy Maertens positions itself at the front of the peloton, driven by their leader. In that train are well-known tempo riders like Marc Demeyer, Herman Vanspringel, Herman Beyssens, and Michel Pollentier. The pace is so incredibly high in those last kilometers that the peloton breaks into five pieces. But that combined strength proves insufficient to rein in the world champion. It’s unbelievable what Kuiper achieves in those last fifteen kilometers. Photographer Tonny Strouken, who rides ahead on a motorbike for the leaders, says: ‘I had never seen anyone ride so fast.’

In the final sprint, Hennie - oh wonder - beats the Swiss ‘sticky rider’. Although the Dutchman deviated from his line, the jury does not find the violation serious enough to take away his victory. However, his helper, De Cauwer, finishes behind the peloton. Three kilometers before the finish line, the Flemish rider gets a flat tire. He crosses the line one and a half minutes later than Kuiper, but he doesn’t care much about it. His protege is the winner; then nothing else matters. It is Hennie’s first Tour stage victory in his career; it is also Raleigh’s first stage win in a seemingly endless series. In the period 1974-1983, Raleigh achieves no less than 47 Tour stage victories and is the strongest team in nine team time trials. The streak only ends when the British sponsor withdraws from cycling as a main sponsor at the end of 1983.

The 1976 Tour team lifts team manager Peter Post with bike and all. From left to right: José De Cauwer, Gerrie Knetemann, Ko Hoogendoorn, Aad van den Hoek, Hennie Kuiper, Piet van Katwijk, Jan Raas, Gerben Karstens, Jan van Katwijk and Bert Pronk

Peter Post shows his aces Jan Raas and Hennie Kuiper. Post certainly does not deny his origins. On his lapel, he wears a pin commemorating the 700th anniversary of the city of Amsterdam.

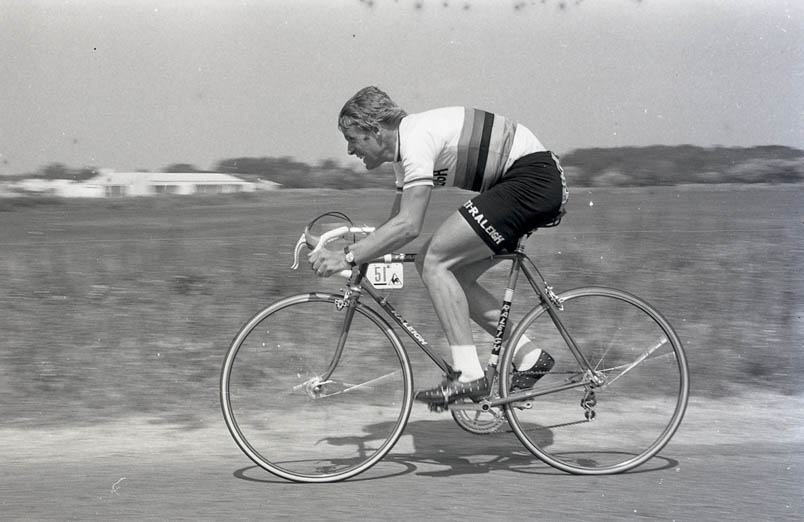

Hennie Kuiper started in the Tour de France of 1976 with the 'lucky number' 51. Eddy Merckx (in 1969 and in 1971), Luis Ocaña (in 1973), and Bernard Thévenet (in 1975) also wore that number during their Tour victories. In the prologue over 8 kilometers around Saint-Jean-de-Monts, Kuiper finishes 23rd.

In the fourth stage of the Tour 1976, Hennie Kuiper leads the large group. To the left of Kuiper are Michel Pollentier and Joop Zoetemelk on the lookout.

Hennie Kuiper sees his chance in the final of the Tour stage to Bornem. The Swiss Eric Loder is already happy that he can keep the wheel.

The large group is chasing Kuiper and Loder. Kuiper assesses the lead and calculates that it should be possible

The victory in Bornem is celebrated greedily with a bottle of Perrier. Left: Joop Holthausen

Hennie Kuiper beats his fellow escapee Eric Loder in the sprint in Bornem. It is not only the first stage victory for Hennie Kuiper in the Tour de France, but also the first stage victory in the Tour for the famous TI-Raleigh team of Peter Post.

A new world is opening up for Hennie Kuiper. On the podium of the Tour de France, he is being pulled in all directions.

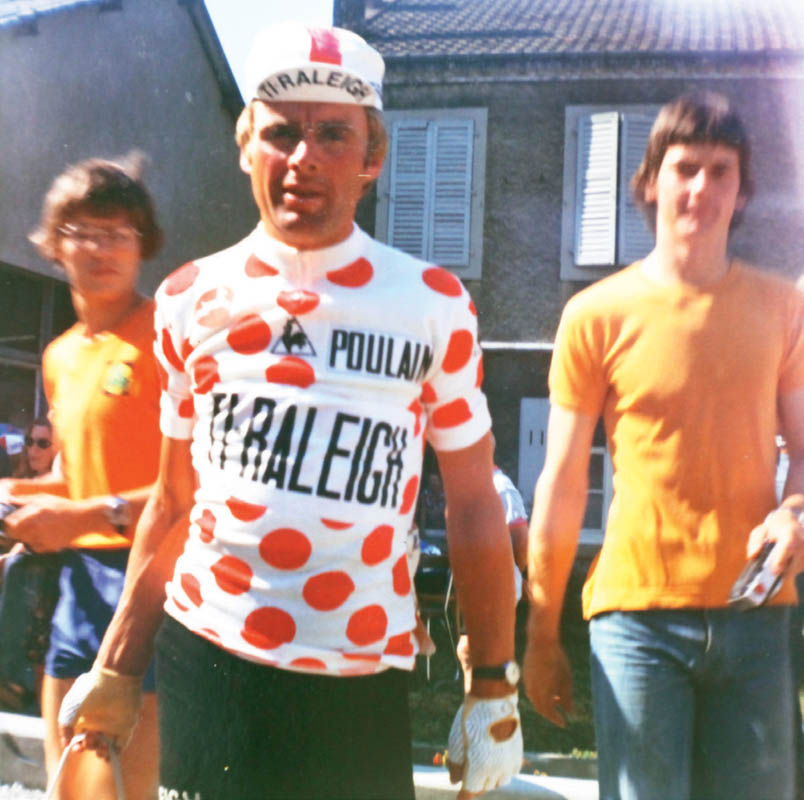

In the stage to Mulhouse, Hennie Kuiper manages to conquer the polka dot jersey. He gets to wear it for exactly one day in 1976.

Loss as a Source of Inspiration

Hennie exhausts himself in the first half of the Tour. He sprints for points on small climbs, chasing the polka dot jersey. In the stage to Mulhouse, as the riders are pushed over the Col du Calvaire and the highest mountain in the Vosges, the Grand Ballon, Hennie gets his wish. He is allowed - even if just for one day - to wear a leader’s jersey in the Tour. However, his real goal is the yellow jersey, and he chooses the stage for his decisive attack, which for the first time since 1952 leads to the top of the ski resort l’Alpe d’Huez. There, he suffers a humiliating defeat. That loss becomes the source of inspiration for his glorious triumph in 1977.

After the defeat in the stage to l’Alpe d’Huez in 1976, he recklessly launches an attack the next day. He wants to cycle away his frustration but fails to realize that he is destroying himself. “There was no team manager Post telling me to ‘Stop!’” There is no teammate to restrain him. Team manager Peter Post, despite his Amsterdam bravado as a great connoisseur of the Tour de France, knows little about the event. Mechanic Paul Soetekouw recalls having to beg for ice cubes in cafes with caregiver Ruud Bakker to cool down drinks in bidons. There are no coolers. No one thought about it, not even Peter Post, who earns his well-deserved living on the winter track as a rider and much less on the road. Post started in the Tour only once, in 1965. But long before reaching the real battleground - the mountains - he abandoned the race.

In Raleigh’s first Tour, Post surrounds himself well. He doesn’t speak French, but he has appointed Belgian tram driver Jules De Wever as his assistant, who is perfectly bilingual. Post appoints his administrative support and coordinator Peter Bonthuis as assistant team manager and supplements his knowledge wherever necessary. When the riders head into the mountains, they ask the team manager for advice on what gear ratios they should use. Post consults José De Cauwer beforehand, who knows almost everything about technical matters. Once he has the information, he urges De Cauwer to keep their conversation confidential.

The big man

In the evening at the table, Post plays the big man and tells with full conviction which gears his riders should use the next day. No wonder that Post cannot provide Kuiper with good advice when Hennie recklessly attacks on the way to Montgenèvre, in a stage with climbs of the Lautaret and the Izoard along the way. He is (still) too inexperienced. It is logical that Kuiper in that stage in the finale - tired as he is - has to let the big stars go, Lucien Van Impe, Bernard Thévenet, and Joop Zoetemelk, who wins a mountain stage for the second consecutive time. It may be considered a miracle that Kuiper still finishes seventh in that stage, but he had to dig deep into his reserves for a performance that does not bring him victory, but loss compared to some important competitors. To make matters worse, two teammates arrive outside the time limit: the brothers Jan and Piet van Katwijk. The cause: the high pace of attacker Kuiper in this stage. ‘You do good things, but also stupid things,’ he concludes afterwards.