A legendary stage

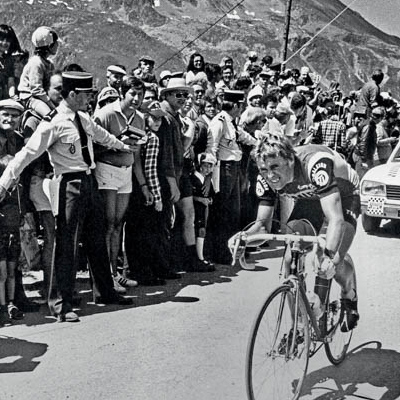

Crucial is the stage to l’Alpe d’Huez. But for Hennie Kuiper there is an extra motive. Actually, for him the journey to the legendary mountain, edition 1977, begins a year earlier on Sunday 4 July 1976 when he mentally and physically collapses at the foot of l’Alpe d’Huez. ‘In the 1977 Tour, I wanted revenge, especially on myself.’ And he is determined to make his personal punitive expedition a great success.

On this day in 1977, Hennie will write the second Dutch chapter in the book that will be called ‘The Dutch mountain.’ None other than Joop Zoetemelk preceded him.

Over the years, l’Alpe d’Huez has gained a magical sound in the Netherlands. This is solely due to the victories of Dutch cyclists in the seventies and eighties of the previous century. Joop Zoetemelk (1976 and 1979), Hennie Kuiper (1977 and 1978) and Peter Winnen (1981 and 1983) triumphantly crossed the finish line twice in those years. Steven Rooks (1988) and Gert-Jan Theunisse (1989) are the last Dutch winners on that Alp, which has since been referred to as the ‘Dutch mountain.’ Perhaps a bit exaggerated, because in 2017 we are still waiting for a Dutch successor to Theunisse.

The finish line of a Tour stage has been drawn on this mountain no less than 29 times in history. Until 1952, l’Alpe d’Huez played no role in the Tour de France. The initiative to bring the Tour caravan to this mountain in the Isère department comes from cycling fans from Bourg d’Oisans. They draw the attention of the Tour director, Jacques Goddet at that time, to the possibilities of the mountain, which is still passable beyond Huez. L’Alpe d’Huez is a developing ski resort during that period.

In 1952, it’s time. Goddet makes a number of innovations in the Tour. For the first time in history, he draws the finish line on top of a mountain. Since 1910, cyclists have been racing over Pyrenean and later also Alpine giants, but the finish line has always been in a valley. In 1952, Goddet decides to end the stage at the top. L’Alpe d’Huez therefore gets a premiere.

The Tour director does not stop at that one experiment but plans two more arrivals on mountaintops in that same Tour: in Sestrières, Italy and on Puy-de-Dôme, the lava dome in the Massif Central, west of Clermont-Ferrand. There is another first. For the first time, there is a cameraman in the Tour who follows the riders all the way to the top. After arrival, the film is transported to a studio as quickly as possible and that same evening television-watching France can feast their eyes on images of a stage that was raced earlier that day.

Leather Head

In 1952, the riders started for the stage to l’Alpe d’Huez over 251 kilometers in Lausanne, Switzerland. The battle ignites only fifteen kilometers before the finish. Then, to the great joy of the French followers, the French climber Jean Robic attacks, five years earlier winner of the Tour. Robic is a remarkably small man, who earns ridicule in the peloton because every time before he starts a descent, he puts on a leather helmet on his head. He owes his nickname “tête de cuir” (leather head) to this habit. In those years, no one wears a helmet. It is considered bothersome and especially childish to protect the head from the consequences of potential falls. A real man does not use a helmet. Risks are simply part of the job.

In 1991, the international cycling union wants to make wearing a helmet mandatory, but the professional peloton goes on strike. It is not until 2003, after Kazakh rider Andrej Kivilev dies in Paris-Nice as a result of a fall, that the peloton agrees and no one rides without a helmet anymore.

In 1952, during the first ascent of l’Alpe d’Huez, even Jean Robic does not need a helmet. There is no descent after the finish. The finish line in 1952 was drawn in the village of Huez, about six kilometers lower than it is now.

After Robic’s attack, the legendary Italian Fausto Coppi launches a counterattack, catches up with the Frenchman, and then grinds away in one steady pace without worrying for a moment about Robic, who struggles at Coppi’s wheel. Six kilometers before the finish, the Frenchman drops off groaning. Coppi soars in champion style to a majestic victory, as he is also invincible a day later in Sestrières and later on Puy-de-Dôme. These victories significantly contribute to Coppi’s second Tour de France win, where he finishes with almost half an hour lead over the second-placed Belgian Stan Ockers. Coppi’s impressive victory on l’Alpe d’Huez does not receive an equally enthusiastic reception everywhere. The chief of the cycling editorial team of the organizing sports newspaper l’Équipe finds it disappointing that nothing happened until the foot of the mountain. Followers describe it as an ‘extremely boring stage’. This criticism leads to l’Alpe d’Huez not being included in the Tour route for more than two decades.

In 1976, the caravan finally heads back to the top of Alp. The finish line is now drawn much higher than in 1952. The road has significantly improved compared to then. L’Alpe d’Huez has been discovered by the masses as a ski resort. Chalets have appeared here and there. The tourist industry is booming. The Tour is more than welcome there because - as experience elsewhere shows - a Tour stage gives a significant boost to a ski resort; business owners are willing to pay for that boost. And so, in ‘76, cycling fans are once again lining up on the slopes of the Alpine giant.

In the Tour de France of 2003, many winners of a Tour stage to the top of Alpe d’Huez are honored. Standing from left to right: Faustino Coppi (son of and therefore stand-in for Fausto Coppi, the first winner in 1952), Peter Winnen (1981, 1983), Joop Zoetemelk (1976, 1979), Roberto Conti (1994), Giuseppe Guerini (1999), Lucho Herrera (1984), and Hennie Kuiper (1977, 1978). Sitting from left to right: Steven Rooks (1988), Bernard Hinault (1986), Iban Mayo (2003), and Lance Armstrong (2001)

Hennie Kuiper delivers an unparalleled performance on the slopes of l’Alpe d’Huez in 1977. The ride is a revenge on the result of the same climb in the Tour a year earlier. The relief at the finish line is immense. With pope-like gestures and blowing kisses, the victory is celebrated. However, Kuiper is so focused on the stage win that he remains eight seconds away from the yellow jersey.

Hennie is parked

On that day in ‘76, Hennie is part of a group that enters Bourg d’Oisans about eight minutes before yellow jersey wearer Freddy Maertens. Hennie surveys the group. He is the best ranked and already sees himself in yellow. The Italian Gianbattista Baronchelli has indeed attacked, but he is no match for the leader of the Raleigh team. He is sure of it: tonight he will proudly wear the yellow jersey at the top of the standings.

Kuiper feels good and is highly motivated. He shifts gears. The first turn, at number 21 (the turns are numbered from 1 to 21, starting at the top). But then, as the group pushes through the first steep meters, it’s as if all strength drains from his body. He completely blocks. Kuiper is ‘parked’, as they say in cycling terms.

It’s a huge struggle. For every meter, he has to dig deep into his reservoir of strength. Is it the fear of the still timid Kuiper, soon to be faced with a massive influx of press attention in the yellow jersey? Is it sudden doubt in his own abilities? ‘Gear too small,’ as Peter Post assumes after that stage? It’s an explanation that doesn’t make much sense, because if Hennie pedals too lightly, he will see his competitors slowly pull away from him. But now they have disappeared in an instant. No, Hennie is completely blocked. The cause of the failure on l’Alpe d’Huez in 1976 must be sought more in the mental than in the physical realm.

Jan Janssen, the first Dutch winner of the Tour de France in 1968, recognizes that feeling of panic, the blockage. It happens to him at the 1964 World Championship. On the course in Sallanches, France, he is on his way to the finish line with Italian Vittorio Adorni and French favorite Raymond Poulidor. It is clear to everyone that one of these riders will soon be able to wear the rainbow jersey. And Jan Janssen is the best sprinter of this trio. So…

Then it flashes through Jan’s mind: ‘I can become world champion here. But then? Will I have all those French journalists on my back? I don’t speak a word of French.’ Janssen panics completely. He feels like he’s not moving forward anymore. In sight of the finish line, he blocks. ‘It lasted until I saw the finish banner hanging there. Then everything fell off me and I sprinted to the world title. That blockage of Hennie’s, yes, I recognize that feeling.’

Calvary journey

While Janssen regains his self-confidence in ‘64, twelve years later Hennie continues to push himself up l’Alpe d’Huez like a dilettante. He sees everyone and everything passing by, not only Joop Zoetemelk, the eventual winner, but numerous riders who normally finish far behind him in the mountains. In the final kilometer, he experiences the lowest point of his calvary journey. Under the red flag, Freddy Maertens overtakes him. Kuiper cannot feel more humiliated. ‘Apparently, some extra salt had to be rubbed in the wound.’ But Hennie wouldn’t be Hennie if that humiliation didn’t lead to deep feelings of revenge within him. Desire-Believe-Act. It is Hennie’s mantra. The desire to take revenge on himself, he has had immediately after his downfall in 1976. The belief that he can do it has been growing day by day since his defeat. And the moment of ‘Acting’, of realizing the desire and belief in it, comes on Tuesday, July 19, 1977 in the stage from Chamonix to l’Alpe d’Huez.

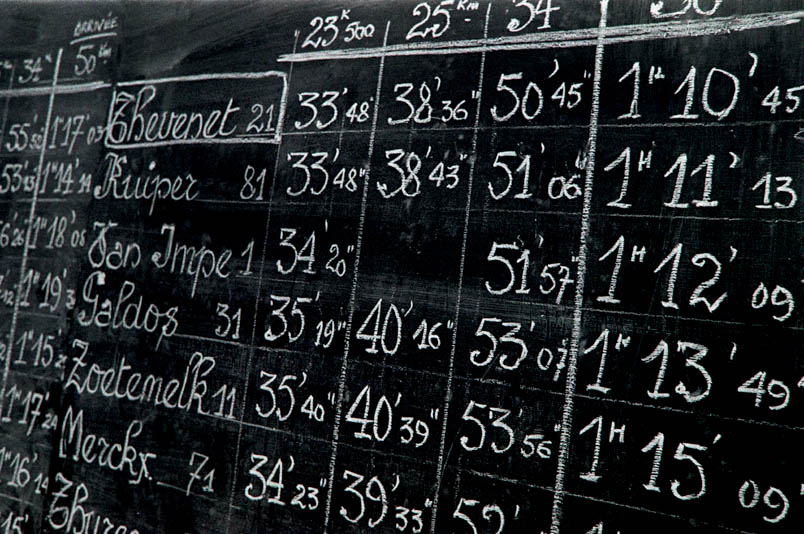

The situation on the eve of the seventeenth stage, leading from Chamonix to l’Alpe d’Huez, is as follows: Bernard Thévenet wears the yellow jersey thanks to his second place in the time trial at Avoriaz. He leads Didi Thurau by 11 seconds. The Belgian Lucien Van Impe, winner of the 1976 Tour, is trailing by 33 seconds and Hennie Kuiper, fourth in the standings, follows the French yellow jersey wearer by 49 seconds. The riders have to cover 184 kilometers between Chamonix and l’Alpe d’Huez. Before the final climb, there are two more first category climbs: the Madeleine and the Glandon, mountains known as ‘silent killers’ because they sap your strength. In short, it is a stage that will demand everything from the riders, rightfully dubbed as the queen stage. Hennie Kuiper is not the only one with big plans for that Tuesday, July 19th. Belgian climber Lucien Van Impe wants to secure his second Tour victory with a devastating attack. The starting situation for the diminutive Van Impe is not as favorable as a year earlier when he was surrounded by stronger support. In 1976, he had Cyrille Guimard as a team manager who understood and guided him excellently. And with Frenchman Raymond Martin, he had a domestique who could keep up in high mountains. He lacks that support in the Lejeune team. Moreover: Henri Anglade is a team manager who can tell great stories, likes to play the role of a great leader but does not excel in race insight in reality. Van Impe is well aware of all this himself. But he trusts in his own qualities as a climber. After all, in the mountains you mainly have to do it yourself.

The overall leader Bernard Thévenet knows that it is also a decisive stage for him. He will focus on defending. He sees Van Impe and Zoetemelk as his main competitors; Kuiper is indeed dangerous but he does not believe the Dutchman is capable of opening a decisive gap on the final climb. On the Madeleine, Hennie Kuiper launches an attack first among the favorites. He is reprimanded by none other than Eddy Merckx. Merckx, who is far from being in top form, wants to keep the pace low for as long as possible. ‘Are you crazy?’ he shouts at Kuiper. No, crazy is certainly not Hennie’s style. His action causes the group to split up.

The main actors remain calm on the Madeleine.

There is a small group led by Henk Lubberding, Christian Seznec, André Chalmel and Jacques Esclassan who launch an attack and will hold out relatively long. Lubberding has been designated by Peter Post as the man who should join an escape in this stage. The escapees are caught up during the climb of the Madeleine.

Lucien the climber

It’s scorching hot on this 19th of July, a whopping 35 degrees. It’s also a historic day in the Tour, an unprecedented battle of attrition. The first ten riders reach the top of the Alp one by one. The tenth rider already has a ten-minute gap. Not less than 31 riders cross the finish line after the time control has closed. And the greatest cyclist of all time, Eddy Merckx, is almost 14 minutes behind at the finish line. But we are far from that point when the scantily clad spectators on the slopes of the mountain eagerly await the caravan of riders. Music plays, there is baguette and wine, as often seen along the Tour route. For both French and foreigners, it’s a celebration. Of course, they come for the cyclists. But they want to experience more than just the twenty, thirty minutes they can see riders pass by in a mountain stage. The pace in the front group is high and claims more victims as it progresses. The men without climbing legs – the mountain-haters – have fallen behind much earlier. For them, this stage is a survival journey. They hope to reach the finish before the time control closes. A ‘bus’ is formed: a group of riders who climb the mountains in a closed formation, far behind the better climbers. The ‘bus’ has a ‘driver’, a rider who sets the pace and calculates as accurately as possible the margin needed to arrive on time. But the pace at the front is high, very high.

Rearguard

Paul Soetekouw, driver of the second team car, is not at ease. He urges the Raleigh riders in the rearguard peloton - Piet van Katwijk, Aad van den Hoek, and the Brit Bill Nickson - to hurry. In vain. The whole group of 31 riders only reaches the finish after the time control has closed and is taken out of the race. Perhaps things would have been different if the Belgian sprinter Rik Van Linden had not been there. Van Linden is a candidate for the green jersey. And because his main rival, the French Peugeot rider Jacques Esclassan, has already finished, Tour director Félix Lévitan does not need to show any leniency. Peugeot is one of the main sponsors of the Tour. And it’s always nice when you can please your most important financial supporter.

All of this is not a concern for the men at the front, who are preparing for the decisive battle. On the Glandon, the audience sees the Belgian Lucien Van Impe pedaling effortlessly uphill. Lucien’s gloomy thoughts from the weeks before the Tour have disappeared. Back then, the pure climber was in a pessimistic mood. ‘What am I doing here? This Tour de France only has one uphill finish. Here I have no chance.’ As the race progresses, his self-confidence grows. And after the Morzine-Avoriaz time trial, which he wins, the Belgian is certain: I can compete for the overall victory. He has only one chance to put his competitors at a disadvantage: the stage to l’Alpe d’Huez. As a born climber, he can shake off Thévenet, Zoetemelk, and Kuiper. Lucien is ready. Let that stage come.

This self-assured attitude leads to overconfidence. On the Glandon where he wants to test his rivals, he sees that no one can follow him. The gap quickly widens: 20 meters, 100 meters, 300 meters. There are still 50 grueling kilometers to go until the finish line. What to do? But he feels so strong that he decides to push on. It’s all or nothing. Hennie Kuiper sees Van Impe pulling away. ‘I felt strong enough to jump to him, but I restrained myself, especially because it was still far to the finish.’ He saves his strength for the final climb.

It turns out to be a wise decision, as later events will show. After descending from the Glandon, the riders not only face fourteen more climbing kilometers to the top of Alpe d’Huez but also about fifteen more or less flat kilometers in the valley between the mountains where the wind blows strongly against them. A year earlier - in a duel with Joop Zoetemelk - Van Impe had received (whether paid or not) support from Luis Ocaña in a similar situation, but now there is no back to hide behind.

At the top of Glandon, Van Impe already has a 30-second lead. Behind Van Impe, a game of poker is being played. Zoetemelk and Kuiper refuse to cooperate. They want Thévenet to do the work. Team manager Maurice De Muer forbids Thévenet from taking turns at the front. Lucien marches on superbly. Due to his pursuers’ passive attitude, he extends his lead to more than three minutes. He already dreams of wearing the yellow jersey at the top.

Bernard Thévenet starts to get worried. Thévenet decides to ignore De Muer’s words and launch a counterattack. The two Dutchmen, Joop Zoetemelk and Hennie Kuiper, stick to Thévenet’s wheel. The Frenchman can keep asking for support but receives no help. After all, he is leading the race? He must defend himself and it’s about time. At the foot of l’Alpe d’Huez, nothing has changed. Van Impe still has a three-minute lead. Joop Zoetemelk makes two attempts at breaking away at the beginning of the climb but is quickly reeled back in. It seems like an act of desperation. ‘I wasn’t in great shape either,’ he recalls forty years later.

En danseuse

Lucien Van Impe can deepen his lead on the chasers in the first kilometers of the climb. Sometimes sitting on the saddle and later standing on the pedals, continuing his way in danseuse. But slowly Van Impe begins to weaken. The trio behind him starts to nibble at his lead. Under the impetus of the yellow jersey wearer, Zoetemelk and Kuiper also get closer. For Hennie, the climb of the Alp is a great celebration. He now truly belongs among the great stars who are fighting for the Tour victory on this mountain. His battle plan is as simple as it is daring: attack, give it everything to avenge the humiliating defeat of a year ago. It is no longer about tactics now, but about the legs. Does he - Hennie - have more reserves than the others? Van Impe’s lead is decreasing. Just over six kilometers from the top, another time check is taken. Theo Koomen, the world-famous sports commentator in the Netherlands, enthusiastically reports on Radio Tour de France: ‘Van Impe still has 2 minutes 35.’ That is almost a minute gained by the chasers compared to the previous checkpoint. ‘Van Impe weakens.’ Anyone analyzing the TV footage from that time can see that the Belgian is struggling. He no longer has that smooth pedal stroke with which he initially danced up the mountain.

Hennie’s Attack

Two, three hundred meters further, the unbelievable happens: Hennie attacks. It is not the kind of attack we are used to from him - not gradually increasing the pace - no, Hennie flashes away. In less than a minute, Thévenet and Zoetemelk find themselves defeated. Kuiper is untouchable today. He hears his name being called from the side. Cheers of admiration. Wherever he passes, applause rings out. It is a triumph. ‘I had goosebumps. Pure emotion.’ Post drives the team car alongside. Finally, Hennie also receives recognition from that side. The gap to Van Impe quickly diminishes. Shortly after his attack, Kuiper has already closed in by twenty seconds. Koomen goes wild. ‘Beautiful, Hennie. Keep it up. He seems to be on his way to victory.’ He not only seems to be on his way; he is on his way to winning the queen stage. Cycling fans experience the Van Impe-Kuiper battle as a breathtaking thriller. A French TV station clocks it twice. Kuiper’s gap now only 1 minute and 40 seconds. A little later: only 58 seconds. The leader of the TI-Raleigh team is putting on a magnificent performance.

First or second: it doesn't matter to mother Kuiper. She is proud of her son: 'Well done, boy'

The podium for the tribute to Hennie Kuiper on l'Alpe d'Huez is far from what it is today. Yet it is a place to see and be seen. This time, the honor falls to Belgian singer Annie Cordy to kiss Kuiper. All the way to the left on the podium stands - with sunglasses - team manager Peter Post proudly.

The twentieth stage of the Tour de France in 1977 is an individual time trial over 50 kilometers to the French mustard city of Dijon. The difference between Hennie Kuiper and Bernard Thévenet is not much, but enough to not be able to threaten Thévenet's yellow jersey.

Voor de aankomst en de huldiging van Hennie Kuiper op de Champs-Elysées rukt een klein legertje Twenten uit naar Parijs. Op de zondag van de ‘arrivée’ poseren de Hennie Kuiper-fans voor de Eiffeltoren. Helemaal vooraan, uitgedost met witte Raleigh-pet en een witte handtas in de aanslag, de moeder van Hennie Kuiper. Links van haar de weduwe van Hennie’s eerste trainer, Broer Oude Keizer.

Van Impe knocked over

And then: a car from the French television knocks over Lucien Van Impe. The Belgian disappears into a ditch, is helped up by spectators. Late, much too late, team manager Anglade rushes to the scene. When Van Impe is finally back on the bike, Hennie passes by the spot of the incident. Shortly after, Van Impe has to get off the bike again. He has a flat rear tire and his rim is bent. Team manager Anglade is still at the scene of the accident. When he finally arrives at Van Impe, Hennie is already out of sight.

Kuiper fights and fights for every meter. It can’t go wrong now. The French are only focused on one thing: maintaining Thévenet’s yellow jersey. The margin of the Frenchman compared to Kuiper is only 49 seconds. If Hennie has 1 second more advantage at the finish line, Thévenet loses the jersey. A French TV commentator, when Thévenet reaches the first houses of Huez: ‘Bernard Thévenet still has the jersey. Kuiper is ahead of him by 44 seconds. The margin is big enough for Bernard at this moment.’ Three hundred meters further, at the moment when the Frenchman passes through the center of the village. ‘In the general classification, Kuiper and Thévenet are now tied. Kuiper has a 49-second lead.’ Hennie Kuiper is one hundred percent focused on winning the stage; on revenge for the humiliating defeat on this same mountain in 1976. He is not at all concerned about the yellow jersey. ‘Peter Post didn’t warn me either,’ says Hennie. Joop Zoetemelk doesn’t see that as an excuse. ‘I always know exactly how things stand in the classification. That’s the responsibility of the rider himself. If he doesn’t know that, he can only blame himself.’

Triumph and Defeat

Kuiper rides under the red flag. ‘At that moment, I already hear the music playing in my subconscious. I enjoy every pedal stroke. That crowd, all those people…’ A support staff member notes that Hennie’s lead is almost a minute at that moment. He is virtually wearing the yellow jersey. Only 1000 meters to go. It feels like all the misery and fatigue of the day are overwhelming him at that moment. He maintains his pace, but weakens slightly.

Well before the finish line, he waves his arms in sheer happiness. Hennie is the king of l’Alpe d’Huez. This is what he has been living for all year.

He wins the stage. ‘This victory is the most beautiful of all my Tour years.’ But at the same time, he loses the Tour. By a mere eight stupid seconds… That realization will only hit him later. For now, he wants to savor every drop of joy from the victory cup.

Never in his illustrious career will Hennie come closer to a Tour victory than on July 19, 1977. Never has he been closer to the yellow jersey, which he will never wear in his career. For Hennie, July 19, 1977 is both the day of his greatest Tour triumph and his greatest loss.

There is one rider who is an even bigger loser on that day: Lucien Van Impe. There are Belgians who claim that Van Impe would have won the Tour de France if he had not been hit by the car of the French TV. Nonsense. Hennie is the best that day. He closes in rapidly on Van Impe, almost able to touch him at the moment the Belgian is hit. Lucien, the best climber in the field, is already a sitting duck.

The cause? There are two causes. The first: he attacks way too early, on the Glandon with still 50 grueling kilometers ahead. He hopes to get one or two riders to join him, but when that doesn’t happen, he still pushes on instead of waiting for the final climb. Remember: he is only 33 seconds behind Thévenet in the standings. It should be very easy for him to gain a minute and a half on Thévenet on that final mountain, giving him enough margin for the last time trial.

But Van Impe makes a second mistake during his solo effort. He forgets to eat as he extends his lead in the valley on his way to the final climb. A car can’t run without fuel, a rider can’t race without food. And so, Van Impe experiences the infamous hunger knock during the climb. Once you feel that, it’s too late. You can’t fix it by quickly eating something. You feel your strength draining from your legs. That’s exactly what happens to Lucien, weakening and allowing both Hennie Kuiper and later Bernard Thévenet to pass him.

There is another big loser: Didi Thurau, Post’s hero. He meets a disgraceful end on l’Alpe d’Huez, realizing he will never be able to win a Tour. When he crosses the finish line exhausted, Thurau gets into a scuffle with supporters out of frustration. He wears the white jersey of the youth classification but refuses to attend the protocol ceremony to collect a new jersey. He leaves angrily and humiliated for the hotel where the TI-Raleigh team celebrates their leader Hennie Kuiper’s triumph.

No one needs to have studied for it to recognize the grumpiness of Hennie Kuiper on the podium in Paris. Bernard Thévenet is being feted by the sponsors on the left, Hennie Kuiper is very annoyed.

Eight counts

Eight counts separate Kuiper from Thévenet after that eventful stage. It may not seem like much, but under those circumstances, it is an almost insurmountable gap, as his advisor José De Cauwer explains. There is only one minimal chance, on the way to the final stage in Paris, to still displace Thévenet from the top position in the general classification: the time trial in Dijon. But Thévenet has a significantly better starting position than the Dutchman. He wears the yellow jersey, which is a great advantage morally. With that jersey on your shoulders, you can always give a little bit more. An additional advantage: during the time trial, you are accompanied by a legion of motorized photographers and cameramen, who swarm around you for the ideal shot of the - then presumed - Tour winner. You benefit from the draft of the motorcycles much more than the second-placed rider in the standings, Kuiper, who although has a decent time trial in his legs, usually falls short against Thévenet.

On the eve of the time trial, Post engages in a sort of cold war. He demands extra measures for doping control. He wants to eliminate all possibilities of fraud. The French media rile up the public. The soigneurs guard the food and drinks that the riders need during the race. They want to make sure that malicious individuals do not tamper with them. The mechanics fear sabotage by hotheads. Mechanic Soetekouw and his colleague Jan Legrand take the bikes of the key men to their bedrooms at night. No risk, is the motto. They want to prevent Hennie Kuiper from being eliminated by sabotage. Legrand, the absolute master of mechanics, thoroughly checks Hennie’s bike once again. Nothing is left to chance. Kuiper fights for all he’s worth, initially even has a lead over Thévenet, but ultimately loses by a difference of 28 seconds. In Paris, there is a 48-second difference between the number one, Thévenet, and number two, Kuiper. And this after 22 stages and 4096 kilometers. The average speed of the winner is 35.419 kilometers per hour.

Mamma Kwiepèr and Valery Giscard d’Estaing

During the celebration on the Champs-Élysées, there may be a hint of disappointment over the lost Tour, but a feeling of pride prevails: our most popular rider has managed to reach the podium of honor. Dignitaries and less notable figures crowd around the rostrum to congratulate Hennie. Mother Johanna is pulled closer. She has traveled by bus with the legion of supporters to witness the festive entry of the Tour gladiators. Mother naturally does not speak a word of French. The phone number of the hotel is written on her arm. If she gets lost, she always finds her way back. But Johanna does not get lost. She finds her way in Paris. Her words: ‘Mamma Hennie Kwiepèr,’ are understood everywhere, even though she speaks those words in pure Twents.

On the grandstand, she sits - together with the wife of the late trainer Broer Oude Keizer and armed with her handbag - close to Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, President of France. Hennie is showered with praise. Beautiful of course, but he is most delighted with the words of mother Johanna: ‘Well done, son.’

Six factors explaining the defeat

In summary, there are six factors that explain why Hennie Kuiper did not win the 1977 Tour.

Factor 1 The victory of the German Didi Thurau in Fleurance means that the TI-Raleigh team has the yellow jersey for the first time in history. Peter Post wants to keep the jersey within the team for as long as possible. He makes everything subordinate to that, including the importance of team leader Hennie Kuiper.

Factor 2 Thurau is, for Post, the embodiment of the ideal rider. Someone with a flashy attack, an excellent sprint, and a formidable time trial. Thurau is a picture-perfect cyclist. He has a great presence, is charming, and can present himself well. Hennie is different: more of a pure attacker, but mainly a worker on the bike, very different from the stylist Thurau. Although Hennie may have an Olympic and a world title on his palmares, he wins much less frequently than Thurau, who goes from one stage victory to the next. In small circles, Post refers to his team leader Kuiper as ‘that farmer’. It is considered disrespectful, as mechanic Paul Soetekouw points out. This shows that Post does not take Hennie seriously. And yet, that same Hennie has always worked so hard for the team.

Factor 3 For the ‘company’, as Post calls TI-Raleigh, the German market is extremely important. The charming German Thurau appeals much more than Hennie to the ideal image of the German sports enthusiast. Just for that reason alone, Post wants to focus on Thurau’s importance from the prologue onwards, which is also the interest of the British sponsor. Hennie comes in second place. In fact, Hennie is used to defend Thurau’s yellow jersey.

Factor 4 Hennie is not assertive. He does not bang his fist on the table when his interests are at stake. So in the stage over the Tourmalet, he not only patiently waits for Thurau to catch up after being dropped, but he also maneuvers the German into an ideal position to win that stage.

Factor 5 In the stage to l’Alpe d’Huez, Hennie is solely focused on a personal revenge; a revenge that should make him forget the humiliating defeat of a year earlier. He impresses in the climb, is a majestic winner, but also a loser because he does not pay attention to his overall classification. His own fault, yes, but Post also bears some blame because apparently he is not focused on the yellow jersey towards the finish either. Otherwise, he would have encouraged Kuiper to fight for every second.

Factor 6 The last factor is a consequence of all previous ones. If Kuiper had not unnecessarily lost 15 seconds in the first Tour stage; if Peter Post had not put everything on Thurau in the first two weeks; if both Kuiper and Post had realized earlier on l’Alpe d’Huez how close they were to the yellow jersey, Hennie would have started the final major task in yellow with a lead over Thévenet: the time trial.

Well, if…

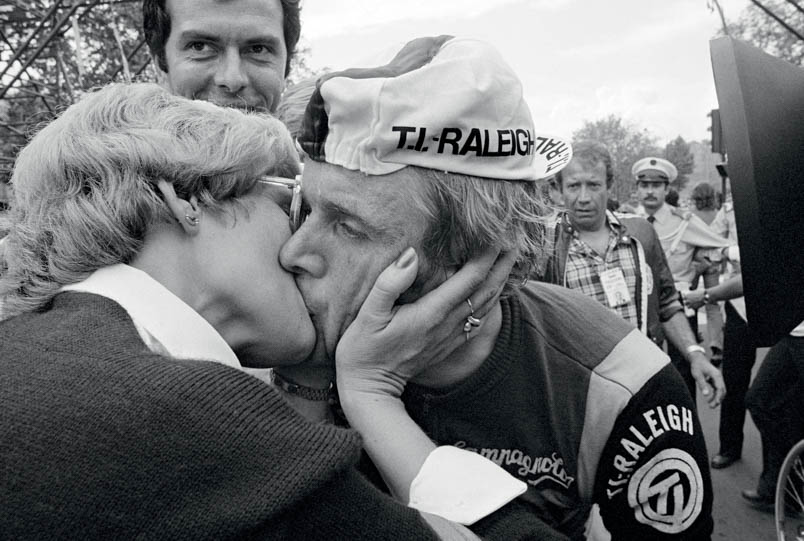

When Hennie definitively ends the Tour de France of 1977 in second place, Ine waits for him with a smack kiss.