The ‘doping’ of Bernard Thévenet

More than a year after the 1977 Tour de France - in the fall of 1978 - the two-time winner (1975 and 1977) Bernard Thévenet confesses. He pours his heart out to Pierre Chany, head of the cycling section of the sports newspaper l’Équipe, the newspaper that, along with Le Parisien Libéré, was responsible for organizing the Tour de France in those days. Thévenet’s confession, published in the magazine Vélo, boils down to him admitting to having used doping along with his teammates from the Peugeot team. Thévenet claims that he was extensively prepared with corticosteroids by team doctor François Bellocq. This led to a lot of physical suffering for Thévenet and a tsunami of negative publicity. The publication in Vélo misleads all media outlets. Thévenet’s ‘doping’ in 1977 should not have been considered as doping. Time for a reconstruction.

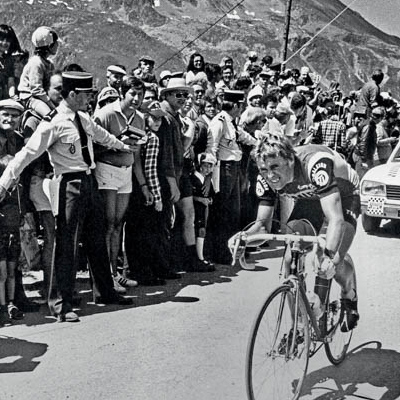

During the Dauphiné Liberé of 1978. The duel Kuiper-Thévenet: supreme concentration from both

Bernard Thévenet did not enjoy his victory in the 1977 Tour de France. In the following winter, he was plagued by severe prostate problems. Throughout the races of 1978, the Frenchman performed below par. He experienced fever attacks in the Four Days of Dunkirk; complained of breathing problems and suffocating tightness in the Dauphiné Libéré. In the Tour de France, he was no longer the rider who had prevented Kuiper from winning a year earlier. At the foot of the Tourmalet, he abandoned the Tour completely exhausted and disillusioned.

In October 1978, Maurice De Muer, sports director of the Peugeot team, obliged his two-time Tour winner to undergo thorough examinations at Saint Joseph Hospital in Paris, where cardiologist Philippe Miserez was also affiliated. Miserez served as head of the medical service of the Tour de France during those years and was familiar with cycling. Miserez’s diagnosis caused a lot of unrest within the team. Almost all riders had submitted to the regimen of team doctor Bellocq. ‘The prolonged and excessive use of the preparations prescribed to you has severely disrupted the functioning of your adrenal glands. This leads to a series of complaints. We refrain from making any prognosis about the future of cyclist Thévenet,’ stated the treating physicians.

Corticosteroids played a key role in the preparations administered to Thévenet and his teammates. It is a synthetic product used by doctors to reduce inflammation and is also used for patients with asthma. It is naturally produced in minimal amounts in the adrenal cortex. Cortisone, which falls under corticosteroids, stimulates glucose production and storage, which is the body’s energy source. The main reason for top athletes to use this substance: it provides more power and suppresses pain, although not all sports scientists endorse this advantageous effect for athletes. Limburg physician Lon Schattenberg, longtime chairman of UCI’s medical commission, emphasizes that corticosteroids do have a positive short-term effect. ‘I can imagine athletes using it in one-day races. It gives a short boost. But in stage races, it can be disastrous. Prolonged use breaks down the body.’

Dangerous situations

Thévenet wants to be open in his conversation with journalist Chany. ‘I am not telling anything new when I say that the use of steroids is widespread in top-level sports today. We, in our team, were convinced that preparing ourselves in this way was the right thing to do. We believed it gave us an edge over the competition. In hindsight, we subjected ourselves to experiments that – as in my case – led to dangerous situations.’

Rumors had been circulating in the cycling world for some time that Thévenet was indulging in banned stimulants. His confession is therefore big news not only in France but also in cycling countries like Italy and Belgium, and… in the Netherlands. After all, Thévenet emerged as the winner in the battle with Hennie Kuiper during the 1977 Tour. A confession, even though it comes almost a year and a half after the 1977 Tour, could – if corticosteroids were banned during that period – have led to disqualification, but that never happened. There are reasons for this, as explained by the former president of the international cycling union, Hein Verbruggen.

The accusing finger in this Thévenet affair points towards Peugeot team doctor Bellocq. Team doctor Bellocq, who passed away in 1993, wrote a book (‘Sport et dopage’) about his experiences in cycling. In it, he showed himself to be a strong advocate for treating cyclists with corticosteroids. Maurice De Muer did not have a good reputation when it came to doping. Doping historian Dr. Jean-Pierre de Mondenard refers to De Muer as the winner of the gold medal in this regard. ‘Between 1970 and 1978, Maurice De Muer had a total of 70 cyclists in his various teams at BIC and Peugeot. Riders were caught doping in 24 cases.’ An incredible score of 34 percent!

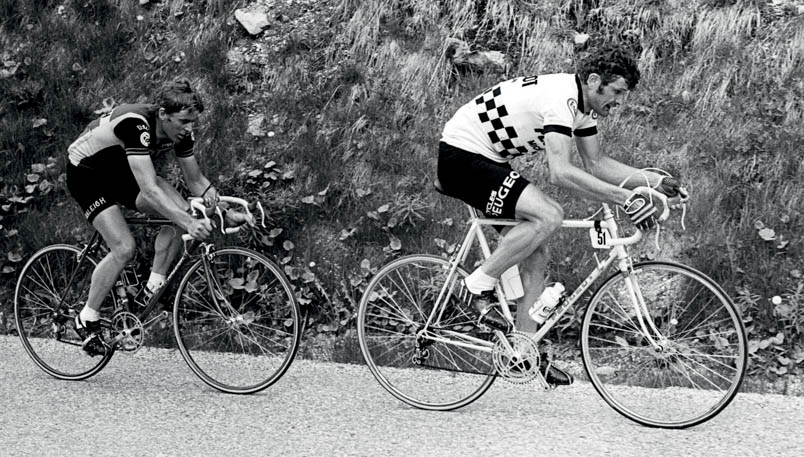

Impressive battlefield on the rough slopes of the Tourmalet. The greats from the 1977 Tour are not yet distancing each other. First: Lucien Van Impe, Hennie Kuiper (on the inside), Bernard Thévenet, and Julian Andiano. Right behind them: Miko rider Raymond Delisle and his teammate Joop Zoetemelk. In the third and fourth positions, Eddy Merckx and Didi Thurau are hanging on.

During the Dauphiné Liberé of 1978. In the battle with Bernard Thévenet, Hennie Kuiper chooses the other side of the road and takes a slight lead. Thévenet neither blinks nor flinches, because he knows: in the high mountains, you cannot show a second of weakness.

Ruining career

Bernard Thévenet accuses Bellocq of ruining his career. And anyone who delves into the Frenchman’s career can understand that. Thévenet’s performance curve shows a erratic course. In 1975, he takes the yellow jersey from Eddy Merckx and wins the Tour de France. The following year, although he is the best in the preparation race for the Tour, the Dauphiné Libéré, his other performances remain significantly below the level of his first Tour victory year. In the Tour de France, he even has to abandon. After his glory year in 1977, a disheartening decline follows. In 1978: no significant victories. In 1979, the year he officially starts at Peugeot as co-leader alongside Hennie Kuiper, third place in a criterium is his best performance and in his last years, 1980 and 1981, Thévenet never rises above the level of a second-rate rider. There is no doubt that Thévenet has harmed himself - on advice from his team doctor. But to what extent do corticosteroids stimulate sports performance?

As for Professor of Movement Sciences Harm Kuipers, former world champion in all-round speed skating, the preparation does not belong on the doping list at all. In an interview with the newspaper Trouw in 2003, he states that corticosteroids do not enhance sports performance. Hennie Kuiper is also not concerned about it. Over all those years, he never insists on punishing Thévenet. ‘What do I gain from it?’ He also prefers not to talk about it. All that fuss about doping only discredits his sport. And indeed: Hennie gains nothing from it. Because even if corticosteroids had been on the doping list in 1977, the user still does not cheat in terms of sportsmanship. Read what Professor Harm Kuipers says in the interview in Trouw: ‘Corticosteroids do not enhance performance.’ It is worth consulting the list of banned substances by the UCI from 1977. This turns out to be not so simple. Limburg medical practitioner Lon Schattenberg is closely involved in the medical records of the International Cycling Union during those years. In his personal archive, he cannot determine the date when corticosteroids were added to the doping list. He hesitates, dares not make a statement about it.

Hein Verbruggen

The former president of the UCI, Dutchman Hein Verbruggen, who passed away from leukemia on June 14, 2017, was already seriously ill when he was presented with questions about corticosteroids in the second half of May. Nevertheless, he starts investigating and concludes that Thévenet did not violate anti-doping rules regarding corticosteroid injections in 1977. ‘On page 26 of the brochure 40 years of fighting against doping, it is stated that corticosteroids were added to the UCI doping list starting from 1980.’

This is six years earlier than when the IOC included corticosteroids on their list, as Herman Ram, director of the Doping Authority, points out. The world cycling federation often lags behind the IOC list, but in this case, the organization is clearly quicker in imposing a ban than the IOC. The harmful effects experienced by Thévenet may have influenced this decision. The IOC had already discouraged the use of the substance in 1975, asking athletes and doctors to report its use, but there was no sanction at the IOC until 1986. Verbruggen adds: ‘Corticosteroids as such have never been prohibited. The medical reason and method of administration determine whether there is a violation of anti-doping regulations. Even if corticosteroids had been on the list in 1977, it is still questionable whether Thévenet was in violation.’ Moreover: although corticosteroids have been on the UCI doping list since 1980, it will take another twenty years before laboratories are able to conclusively detect the use of the banned product.

All this does not matter in assessing whether Thévenet crossed the line when he received corticosteroid treatment during the 1977 Tour. The product was not on the list in 1977. It remains strange that no one in the media or Thévenet’s surroundings thought to check whether the controversial product - corticosteroids - was on the doping list at that time. Perhaps the fact that the journalist who first broke the news, Frenchman Pierre Chany, classified the product as doping was the reason. Chany was considered an authority. The UCI did not need to defend Thévenet. After all, he had not tested positive during that Tour. The ‘Thévenet affair’ was not a concern for the bigwigs. Strictly speaking, the victory of the Frenchman is undisputed. He was not caught using any prohibited substance during controls. However, doubts will inevitably linger about his victory, especially due to his confession. Thévenet himself has learned to live with it.

Despite the negative publicity surrounding his Tour victory, Bernard Thévenet remains a popular guest in the post-Tour criterium circuit. In the Acht van Chaam of 1977, Piet Bambergen (the cheerful half of 'De Mounties') suddenly becomes his best friend. Thévenet can laugh about it.

On the Tourmalet, climbing is done with the mouth tightly closed. Climbing with an open mouth is indeed a sign of weakness. From the front: Pierre-Raymond Villemiane, Lucien Van Impe, Bernard Thévenet, Julian Andiano, and Hennie Kuiper (who cheats a little by sticking out the tip of his tongue)