Joop wins, Hennie in the shadow

In the spring of 1980, his last season at Peugeot, one performance stands out clearly. In the Ardennes classic Liège-Bastogne-Liège, Hennie Kuiper is the best of the ordinary mortals. He finishes second in a classic race held under Siberian conditions. Hinault destroys the entire field. Kuiper finishes second in this polar expedition. When Hinault later falters in the Tour de France that year, it is partly due to the hardships he endured in the spring. He has put such a strain on his body that he has to pay the price later in the season. The 1980 Tour becomes the Tour of Joop Zoetemelk and TI-Raleigh. Joop does not have his best Tour de France, but he is surrounded by the strongest team: Peter Post’s team. ‘And still Post was not satisfied,’ says Peter Bonthuis, in those days the right-hand man of the Raleigh team manager. ‘Winning the Tour, eleven days in yellow jersey and eleven stage wins. And still being angry. It should have been twelve… Unbelievable, but that was Post.’

In Joop’s shadow, Hennie rides to second place. He owes this mainly to a strong performance in the stage over the cobbles between Liège and Lille (second behind Hinault) and some very strong time trials. Hennie may have ridden the best time trials of his career. In the long race against the clock between Damazan and Laplume, only Joop Zoetemelk is better. However, he leaves behind renowned time trial specialists like - the injured - Bernard Hinault, Bert Oosterbosch, and Joaquim Agostinho. In the mountains, Hennie notices that his results are inconsistent. He does very well in the Pyrenees, but in the Alps, he discovers that he can no longer keep up with the best. He tries to hang on as long as possible, but it doesn’t always work. Kuiper has to suffer terribly to limit the loss. In the final tough mountain stage to the top of Prapoutel, he even briefly loses his second place to the Frenchman Raymond Martin. However, he manages to rectify that in the time trial in Saint-Étienne (won by Zoetemelk). Hennie stands on the podium in Paris for the second time in his career. Hennie’s second place is overshadowed by the celebration around winner Joop. Kuiper has achieved two second places in the Tour de France. The first time, in 1977, all of Netherlands celebrated that second place as a victory. Hennie was a hero in those days. The Tukker became a national darling. Three years later, Hennie Kuiper stands on the same spot on the podium: second. This time it is an anonymous second place. Ask anyone who finished second behind Joop Zoetemelk in the 1980 Tour de France and nine out of ten times you will get no answer or a wrong one. One second place is not like another. It teaches you to put things into perspective. People who in 1977 knocked down everything and everyone to congratulate me now almost push me off the podium to get to Joop. There is no respect for my second place. But that’s how elite sports are.’

Kuiper ends 1980 without a significant victory. Yet he has a good season; his fourth place in the final standings of Super Prestige (the regularity classification) is proof of that. Just behind Hinault, Fons De Wolf, and Moser. He never finished higher in that classification. After that Tour, Kuiper wins two insignificant local races. While Joop celebrates his most beautiful career victory on Champs-Élysées in fashionable Paris in 1980, Hennie settles for a victory in Broek op Langedijk. A greater contrast is unimaginable.

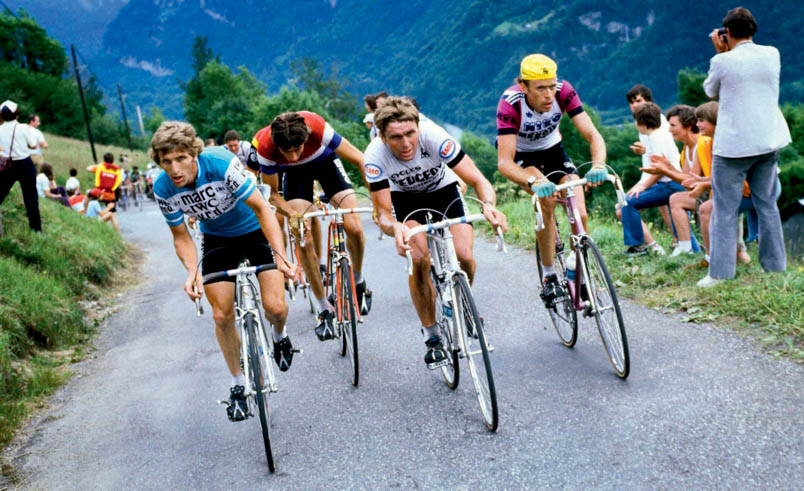

In the 1979 Fleche Wallonne, a tough race is being ridden. Bernard Hinault is almost done. Far left, Fons De Wolf is pushing hard. To the right of De Wolf, Walter Godefroot fixes his gaze on a point in the distance. Just behind Godefroot, Henk Lubberding rides in his national champion jersey. On the right, Hennie Kuiper tries to avoid getting caught up in the struggle.

In the Tour of '80, Hennie Kuiper rides a great cobblestone stage between Liège and Lille together with Bernard Hinault. It is truly Hennie Kuiper weather. Hinault beats Kuiper in the sprint for the stage win. Ludo Delcroix, almost invisible behind Hinault, will receive almost a minute gap as the third in the stage.

A typical North French setting and a typical North French audience at the sixth stage of the Tour in 1980 between Lille and Compiègne

Sharp in the wheel of Zoetemelk with Johan De Muynck behind him. Hennie Kuiper is also attentive on the small climbs in the Tour stage from Lille to Compiègne.

Tour stage 13 in 1980. From Pau to Bagnières-de-Luchon. From left to right: Vicente Belda, Christian Seznec, Hennie Kuiper, Jean-René Bernaudeau, Joop Zoetemelk, and Johan De Muynck

At the foot of the Tourmalet, Raymond Martin has launched an attack, so Zoetemelk has to do the lead work. A day earlier, Bernard Hinault had to withdraw from the Tour due to a knee injury. Joop refuses to wear the yellow jersey in the stage to Bagnères-de-Luchon, but is forced by Kuiper to do all the lead work. To the left of Zoetemelk is Johan De Muynck with Ludo Loos behind him. To the right of Zoetemelk are Kuiper and Robert Alban.

The top of the Tourmalet is shrouded in mist. A ghostly group with Lucien Van Impe, Joop Zoetemelk, and Hennie Kuiper at the front bravely faces the fog.

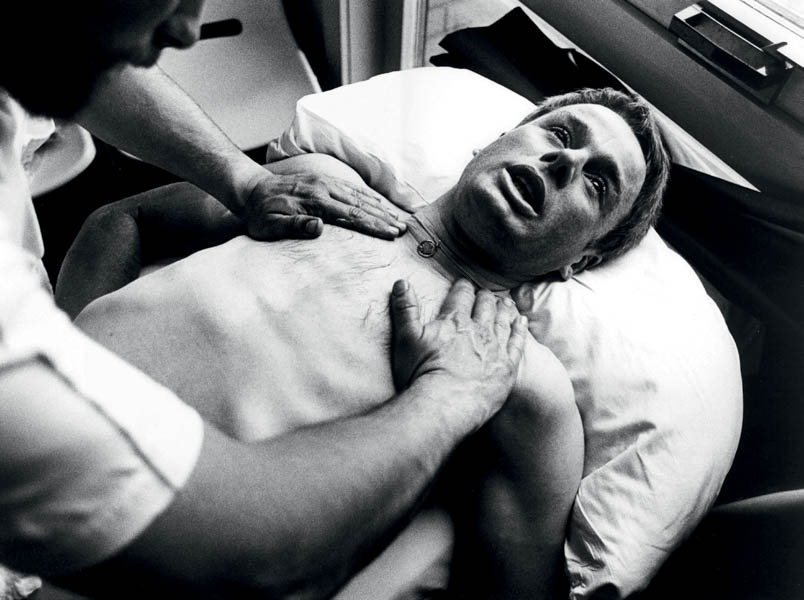

Hennie Kuiper lets the fatigue of a tough mountain ride be massaged out on the massage table in Luchon

Both in stage 17 and stage 18 of the 1979 Tour, the finish was at the top of l'Alpe d'Huez. On the mountain where Hennie made history in 1977, he suffered a dramatic loss two years later. In stage 17, he struggled all alone to the top, where he arrived as number 29 over 8 minutes later than winner Agostinho and lost five minutes to competitors like Hinault and Zoetemelk. The next day, he did better. Winners Zoetemelk and Hinault proved to be too strong for him, but with his eighth place, he still stayed in the wake of the classification men.

No Leader

Hennie already knows at that moment that he is going to leave Peugeot. He has not been able to deliver what the sponsor expects from him. In the Giro d’Italia, the Frenchman Jean-René Bernaudeau does a tremendous amount of work for the eventual winner, Bernard Hinault. The press writes praise for the young talent. At Peugeot, they are eagerly anticipating a new, and especially French star. And Bernaudeau essentially has everything that makes him attractive to the French car company.

Kuiper sees the writing on the wall early on. Only if he can prevent the new leader of the international cycling peloton, Bernard Hinault, from winning the Tour, will there be an extension of his contract.

The love between the Dutch-Flemish duo Kuiper-De Cauwer and the French riders has cooled off. José De Cauwer quickly realizes that the French riders who sit together at dinner in the evenings all claim to have ridden fantastically; at least according to their own accounts. ‘Apparently, they were fantastic that day: I rode at the front; did this, did that. When I hear all of that, I think: Well, then I probably didn’t do anything at all.’

In hindsight, Kuiper feels he was too eager to dive into the French adventure. ‘After a few months, I realized that De Muer was actually only concerned with his position among French team managers. The strategy was focused on everything except letting Hinault, Guimard’s big asset, win. And this with a team that, as I experienced it, was past its prime. Riders like Thévenet, Ovion, Sybille, and Bernard Bourreau had seen their best days.’

According to De Cauwer, during the Peugeot period, it was a struggle against high expectations. It was expected that Hennie would easily win the Tour. ‘From the first day, Hennie was expected to take on a leadership role as team leader, but Hennie is not a leader. He is also not always able to live up to those moments when something great is expected of him. Hennie is not a Merckx, not a De Vlaeminck. He thrives on working hard, then showing off briefly and then disappearing from the scene. Team leadership within a team with personalities like Régis Ovion, Guy Sybille, Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle, and Yves Hézard has never been his thing.’

During the Peugeot years, not only were local criterium races in the Netherlands a lucrative source of income; there were also opportunities at criteriums in France, if only because the sponsor wanted to see the team leader’s jersey in France regularly.

Most criteriums are held in the period immediately after the Tour de France. The riders are tired after completing the world’s toughest stage race but must get back to racing immediately if they want to earn lucrative appearance fees. This also applies to Hennie, who negotiates in every contract that his friend José can also start.

This means covering enormous distances. It is common for Hennie to start in the Netherlands one day and then be somewhere deep in France the next day.

José, the devil’s huntsman

Invariably, De Cauwer acts as the driver. In 1979, De Cauwer drives thousands of kilometers in a month in this way. He is the driver, picks up the race number for his team leader, and ensures that they both find accommodation. Moreover, he is also a participant in the respective criterium. José remembers the time when they once again depart from his house in Temse, near Antwerp, at night because they are expected in a place south of Bordeaux the next day. José is as usual behind the wheel. Hennie is fast asleep even before they reach the French border. De Cauwer drives continuously throughout the night; Hennie sleeps the sleep of the innocent.

When they finally arrive at their destination after that long, long journey, the team leader wakes up, rubs the sleep from his eyes, looks at his buddy and then says, ‘You look terrible!’ De Cauwer shakes his head. ‘It’s unbelievable, but he doesn’t realize that I am completely exhausted at that moment after so many hours behind the wheel.’

Another emotional example is the trip to Brittany, where Hennie is listed for a criterium. Of course, José drives again. The men sit silently next to each other. José, the ever-present helper, driver, organizer, tactician, savior-in-many-a-need, servant-in-the-race, in short: the devil’s huntsman. And Hennie beside him. The extremely driven cyclist, always striving to improve himself, the incredibly strong-willed man with only one focus: cycling.

José’s thoughts are with home. With his Jeanne who suffers from Hodgkin’s disease, who has little prospect left, who is everything to him. She might die. The emotion is understandable. He wants to share the pain and suffering. And with whom better than with the other half of the duo, with Hennie with whom he has been closely friends for years? José says: ‘Hennie, man… I think things are not going well at home.’ Hennie’s response, which he later deeply regrets, is crushing. ‘If that’s how it is, then so be it.’ There is not a hint of empathy in it. Tears stream down José’s cheeks. He says: ‘But Hennie…’ And he falls silent. He knows how Hennie is, but this is very extreme.

The realization only dawns on Kuiper later. He never wants to hurt or offend anyone. That’s not Hennie. He expresses his deep regret afterwards. In many words and in a letter. ‘He apologized a thousand times. Actually, you should blame him for that attitude, but if you know him - as I do - you know he doesn’t mean it that way. But it’s very hard for me. At the moment when you seek a bit of support, you get such a response. I know how he is wired. He is absent-minded. Always focused on cycling. Hennie lives in his own world.’

Hennie Kuiper assesses the two seasons with Peugeot. A fourth and a second place in the only race that matters in French eyes, the Tour de France. You can’t consider that as ‘insufficient’. On the contrary: it’s fantastic! But he didn’t become the winner that De Muer saw in him two years earlier and that he himself fervently hoped for. So after team manager De Muer’s advances towards talent Bernaudeau, Hennie counts his options: he looks for a new employer. Fate seems to be favoring him now. In the 1979 Tour de France, on the rest day in Morzine, he is visited by Willy van Doorne, director of the DAF car factory, who started a cycling team that year. He makes Hennie a nice offer. He wants Hennie to join the DAF cycling team starting from next season. The offer is eagerly accepted.

Ludo Loos (links) will win the stage to Prapoutel. National champion Johan van der Velde squeezes everything out for Zoetemelk. Kuiper rides with a fierce look in his eyes and Christian Seznec (far right) positions his head in the characteristic way between the shoulders in front of him.

In Prapoutel, Hennie Kuiper has temporarily lost his second place in the standings. He loses over two and a half minutes to Zoetemelk's yellow jersey and almost two minutes to closest rival Raymond Martin, who jumps ahead of him in the standings.

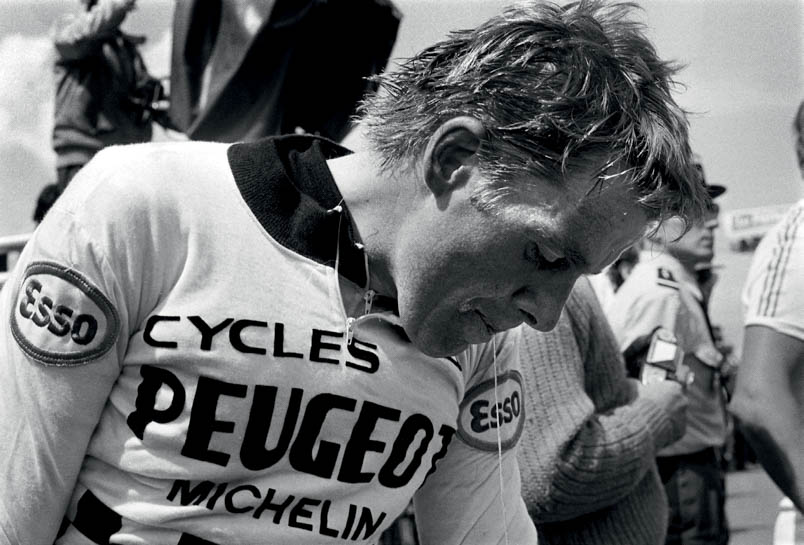

Hennie Kuiper is proud of his second place in Paris, but visibly struggles with mixed feelings. After Jan Janssen in 1968, the Netherlands has a Tour winner again in 1980 in the person of Joop Zoetemelk