‘The real hard work suits Hennie’

In 1981, with the switch to DAF, a second career begins for Hennie Kuiper. At 32 years old, he is starting to feel a bit old as a rider for the major stage races. He can still achieve a good overall ranking, but competing for the top spot is no longer within reach. He realizes this himself. José De Cauwer – who else – had already set him on the right path a year earlier. After a tough stage in the Tour de France through the Vosges mountains, feeling disappointed, Hennie goes to his teammate’s room where José says: ‘You should forget about that overall ranking and focus on the major one-day races: that’s where you excel.’ De Cauwer had already noticed that things were not going as well in the Tour de France. ‘He was still good in time trials, but not world-class. He was also good in the mountains, but again not world-class. In short, he would fall short of being at the top of the rankings.’

Mentor De Cauwer sees it clearly: Hennie is ready for a change. ‘He had already built up a certain reputation in one-day races. He had become Olympic, national, and world champion, achieved good results in numerous classics without specifically preparing for them. Spending six hours on the bike, enduring races on challenging courses, preferably under harsh conditions, pushing himself to the limit: that’s what suited him.’

De Cauwer had already observed: Hennie had reached a turning point in his career. ‘He was already on the decline in his career when he started focusing on classics. If he had focused on them earlier, he could have built a much larger palmares.’ He naturally had a talent for classic races. Just look at his results list. He can present a series of results that many specialists would envy. Between early 1973 and late 1980, the era before his career switch, he finished in the top ten an impressive 35 times in major one-day races such as the Tour of Flanders, Gent-Wevelgem, Paris-Roubaix, Fleche Wallonne, Liege-Bastogne-Liege, Amstel Gold Race, Zurich Championship, Henninger Turm, Paris-Brussels, Paris-Tours, Tour of Lombardy, World Championships and National Championships. A list that unequivocally highlights his aptitude for such one-day races.

From the start of his Raleigh years in 1976, Hennie Kuiper was exclusively labeled as a ‘stage racer’. Post knew that Kuiper could also hold his own in one-day races, but for that specialty he already had men: first Roy Schuiten (which failed) and later Gerrie Knetemann and especially Jan Raas. He lacked a man for the overall classification. Kuiper could fill that vacancy perfectly. Hennie was successful as a stage racer. Although he didn’t win the Tour de France, he was consistently near the top of the standings. Furthermore, he made a name for himself by winning the Tour of Switzerland in 1976. After his Raleigh years, Peugeot team manager De Muer brought Kuiper on board as an asset for the Tour team. Once again, the one-day races took a back seat after De Cauwer’s advice made them the main focus.

Training approach

Kuiper is advised to approach the training differently, to ride on heavier gears in the early spring so that he could handle the big gear in the finals of those major races. De Cauwer makes it clear with a typical Flemish expression what else needs to be improved to transform Kuiper from a stage racer into a classics rider. ‘In the past, he was too heavy in early spring. He always started the first classics races overweight.’ Hennie knows his limitations. He is not fast. In almost every final sprint, he comes up short. Hennie must rely on solo efforts. He needs to drop his competitors before the finish line. And that means he must have the ability to push out heavy wattages in the spring classics. Everything up to 1980 has been focused on the major stage races, especially the Tour. The training has always been geared towards that. Now it’s different, Hennie knows. ‘Because the classics riders will ride with an even bigger gear in the final hour of the race. The pace in the finale goes above 50 kilometers per hour.’

Those who know him see another transformation: Hennie exudes more self-confidence, stands more firmly on the ground. The atmosphere at DAF suits him perfectly. He has a sponsorship director, Willy van Doorne, with whom he has an excellent relationship; José De Cauwer - his close friend - clearly influences the technical guidance of the team; he gets along well with Roger De Vlaeminck, one of the great Belgian stars, and within the team, he is recognized as a rider who, despite his lack of sprinting abilities, has built up a respectable list of achievements. In short: he feels comfortable and this is reflected in a more self-assured attitude.

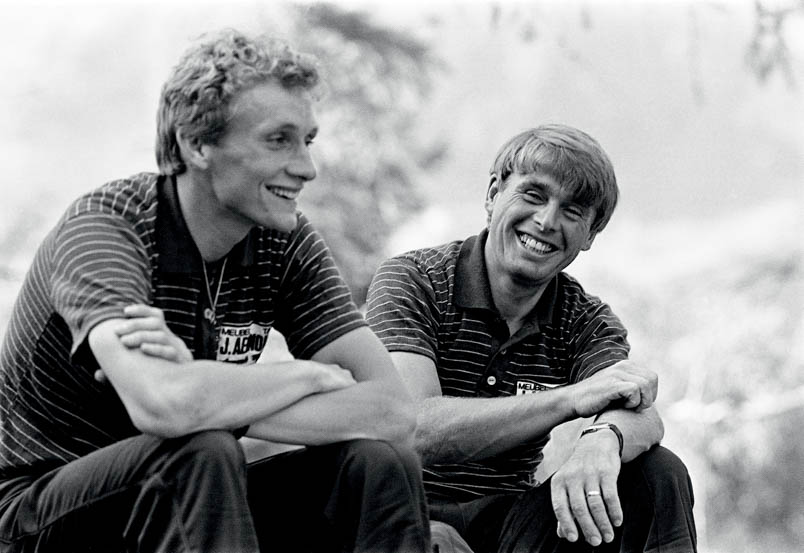

Adrie van der Poel and Hennie Kuiper not only train hard in the lead-up to the 1983 cycling season, but also make time for relaxation.

Hennie Kuiper and Adrie van der Poel have left the Tour de Suisse and are waiting in the feed zone in the trunk of Ruud Bakker's car

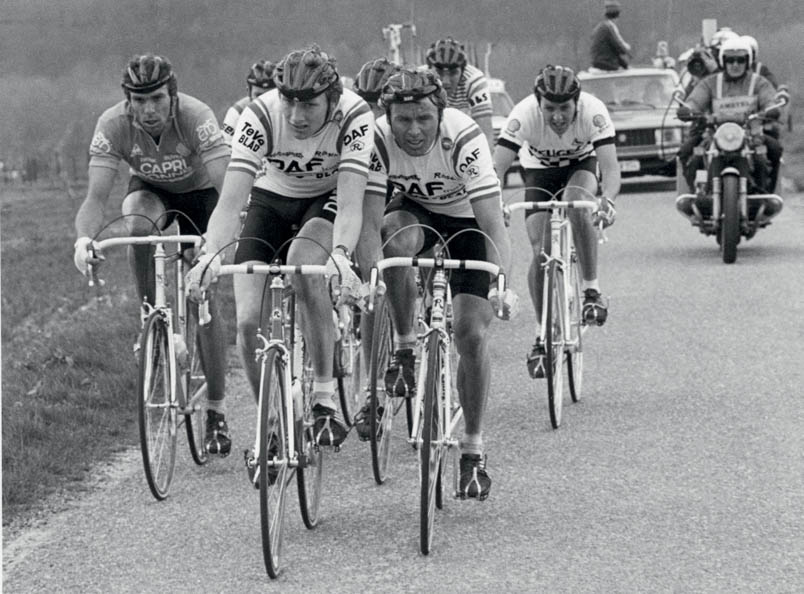

Gregor Braun, Adrie van der Poel, Hennie Kuiper and Stephen Roche on the Keutenberg

The greatest victory

Hennie once had contact with the Amsterdam therapist Len Del Ferro. He claims to have helped Kuiper overcome his stuttering problems. But Hennie puts that claim into perspective. ‘He may have contributed to it at most. I mainly overcame it myself.’ It is true that he received help from others in the process. The personality course LSP, which he attended in the late autumn of 1978, may have played a role, as he himself says, but it is mainly his own merit.

‘It is,’ he says, ‘perhaps been the greatest victory in my life.’

Adrie van der Poel

At DAF, Kuiper meets Adrie van der Poel, also a farmer’s son; not a born Twente resident, but a true Brabander from Hoogerheide. Hennie moved from Oldenzaal to Brabant in 1973, initially to Ossendrecht, later to Putte, where he is almost neighbors with Jan Janssen. Van der Poel and Kuiper got to know each other a bit in the late seventies during training rides; Adrie as an amateur with the Van Erp team, Hennie as a professional rider with Peugeot. Their contact becomes closer when Van der Poel breaks his collarbone in the Ronde van Overijssel in 1980. The Brabander fears for his chances for the Olympic selection. Then Kuiper lends a helping hand. He is still grateful to Hennie for that, he says in his villa in Kapelle, Belgium. ‘He took me to Dr. Johan Derweduwen in Mol, Belgium, who had already helped him with a collarbone fracture before. That doctor operated on me, connected the two bone parts with a screw, and done. I had a very good race at the Olympic Games in Moscow. This was followed by excellent results in the Ster der Beloften. The following season I was on Hennie’s team.’

In the fall of 1980, Van der Poel is a sought-after rider by professional teams: he has endurance and a good sprint. He chooses DAF. ‘The fact that Hennie went there may have played a role. As well as the fact that DAF is a company from this area. What also helped with that choice was that Dutch was spoken in this team. There was no language barrier.’ In his first important stage race, Paris-Nice, he immediately wins a stage and finishes second overall. He is tasked with protecting Hennie Kuiper from the wind, but in the third stage, towards Saint-Étienne, he rides 30 kilometers before the finish to catch up with Kuiper and says: ‘Now you can definitely handle it alone?’ Kuiper replies: ‘Yes, but why?’ ‘I want to try something myself,’ says Adrie. He tries and wins. He is one of the best at the training camp, shows himself at the front in the Omloop Het Volk and soon after gets a free role, unusually fast for a rookie.

José De Cauwer, his sports director in that initial phase, quickly realizes: I just have to let Van der Poel do his thing. Van der Poel is annoyed by statements like: ‘I never get a chance.’ ‘You don’t get chances, you seize them.’ The slender Brabander also does this in other aspects. In that Paris-Nice race, he starts his first French lesson on the massage table. ‘Soigneur Willy Voet, who speaks perfect French and Dutch, practiced with me while massaging: learning words, building sentences. Thanks to him I learned French, although it takes some time before you can manage on your own in such a language.’ Later he will marry Corine, Raymond Poulidor’s daughter, alias Poupou. Van der Poel respects his fellow region mate Kuiper. ‘Of course he had already achieved a lot. But look up to him? No. And even then I felt they didn’t have to do that with me either. I have always tried to practice my profession as well as possible with all the pros and cons that I have inherited from Mother Nature.’

Adrie and Hennie: two opposites

Van der Poel understood the race better than Hennie, and he had to. ‘He was much stronger than me. The longer a race lasted, the harder it was, the better he performed. For me, it was exactly the opposite. I had to hold back a certain reserve, had to know my opponents very well. If they followed a certain tactic, I would do it slightly differently.’ Very different from Hennie. ‘Yes, he was just as fast after 200 kilometers as in the first fifty. Of course, Hennie was super on certain days. Towards the end of the race, he would get better, not so much because he could increase the pace even more, but because his opponents ran out of fuel. Hennie could always keep going. That strength, that strong body, that was his class.’

What Van der Poel learns from his experienced teammate is taking timely rest. ‘Rest, eat, and then rest again. Hennie has often been my roommate. You adapt to that. I had that with Hennie and later with Joop Zoetemelk and with Marc Dierickx, who later became my personal helper. What De Cauwer was to Hennie, Marc was to me. Hennie would lie down on bed after the race and fall asleep. I wasn’t sleepy, but I would also lie down. And after five times, I adapted to that habit of Kuiper’s and also went to sleep. That way you do get your rest.’ De Cauwer had already experienced how strong Kuiper was in training during their time at Frisol. Adrie goes through the same during the training rides he undertakes with Hennie. ‘If he had those days, I shouldn’t make the mistake of trying to keep up with him because I would be bad for two weeks. Occasionally, I needed such a training session, but I had to dose it very well. But it also happened that I said: “Figure it out on your own, I’m not going any further.”’

More than Kuiper, Van der Poel seems destined to play a leading role in the classics with his sprint finish. He compiles a beautiful list of achievements, including two monuments: the Tour of Flanders (1986) and Liège-Bastogne-Liège (1988); he is the best in the Championship of Zurich (1982), in the Clásica San Sebastian, Paris-Brussels, and the Brabantse Pijl (1985) and in the Amstel Gold Race (1990); he wins three Tour stages, wears the yellow jersey for one day, becomes world cyclo-cross champion, but to his regret is not a winner of Paris-Roubaix, his favorite race. He comes close once, in 1983, but initially loses contact with the leading group and then has to hold back to not jeopardize the chances of the eventual winner, his teammate Hennie Kuiper. ‘I have always loved Paris-Roubaix the most. It is a unique race. The Tour of Flanders is also beautiful but not unique. The climbs of Flanders you also encounter in Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, in E3-Prijs and in Driedaagse van De Panne. Before you start the Tour of Flanders you have climbed those hills several times that same season.’ Paris-Roubaix is only once a year. ‘At most you might cross part of the course when the Tour de France passes through that region. But every time you fail to win Paris-Roubaix again, you have to wait another year before starting the most beautiful classic.’ Adrie van der Poel and Hennie Kuiper, two farmer’s sons who share the same dream. But ultimately only Hennie succeeds in fulfilling that dream.

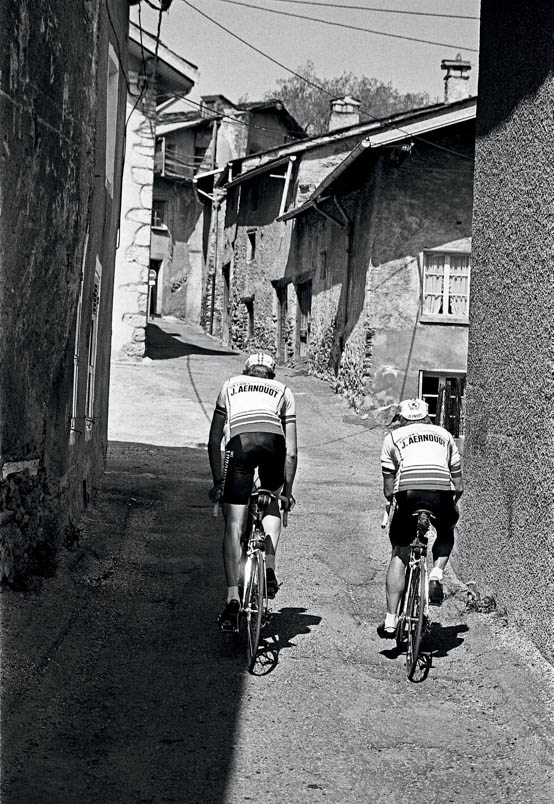

Hennie Kuiper and Adrie van der Poel train together in the French Alps to prepare for the 1983 season