Liège-Bastogne-Liège 1980

Liège-Bastogne-Liège does not belong in Kuiper’s list of monuments. After all, he never finishes as the winner. But because the 1980 edition is all about heroism, because Hennie races to a heroic second place behind a magnificent Hinault on that Siberian Sunday, April 20, 1980, and because this second place also marks the prelude to his transformation from a stage racer to a specialist for one-day races, La Doyenne still belongs in Hennie’s list of monuments; the ‘zero issue’. Like almost all breadwinners, Hennie Kuiper has already endured his fair share of chilling hardships when he starts the great Ardennes classic of 1980. The most extreme is undoubtedly the fifth and final stage of the Tour of Belgium in 1977, the 213-kilometer stage from Fléron to Jambes. On the fourteenth of April that year, it is bitterly cold. It has been pouring rain all week. The muddy fields in Flanders are soaked, and those who, like on this day, race through the pine greenery of the Ardennes have the feeling of constantly being under an ice-cold shower. The riders seek shelter in each other’s dripping bodies, especially because it seems that Walter Planckaert cannot be ousted from the lead position. It is a time when heat patches have not yet made their entrance, when overshoes did not provide the protection they have since the turn of the millennium, when eyes were not yet shielded from rain, snow, or ice by futuristic or not-so-futuristic glasses, and when thermal clothing was not available.

We - two journalists from Het Vrije Volk (Peter Ouwerkerk) and Het Parool (Joop Holthausen) - follow the race in an Austin 7, the size of an oversized dinky toy. In front of us, you can just see through the rain veils the curved backs of the suffering peloton. The temperature drops, the rain stops. On top of the hills, the temperature drops below zero. Menacing clouds hang above the riders. It couldn’t be… Yes, it was predicted: a chance of snow showers in the Ardennes. But it’s mid-April! There are riders who have had enough. The classification is already set. They can’t do anything more. It’s better to get off than to risk catching a cold or flu in this miserable weather. You hear curses from the peloton. And then it snows, first hesitantly and then abundantly. Before us, riders slip on the road, many end up in the ditch on descents. You see riders seeking shelter at farms or immediately asking for a seat in the team car. Continuing to ride is pure madness. To the right of the road, through the snowstorm, you can see a rider in the red and yellow outfit of the famous TI-Raleigh team. He leans shivering and chattering over his bike. We slow down. ‘Stop, stop. Please,’ sounds pleadingly. Damn: that’s Hennie Kuiper, the leader for stage races. A tough guy. It must be really bad if he wants to give up… And it is bad indeed. So bad that alongside Kuiper, 33 men also seek refuge in warm cars prematurely. Of the 67 riders who started in Fléron that morning, only 33 cross the finish line in Jambes.

He shivers

Hennie is frozen stiff. The cold has deeply settled into his body. Can he ride along? We look at each other. Yes, we have a back seat. And if he ruins the upholstery with his dirty and soaked racing suit, well, we can live with that. But a frozen rider plus a complete bike in this dinky toy?

But poor Hennie is shivering so much… Alright, we’ll try it. The wheels come off. The handlebars are turned sideways, Hennie is placed on the back seat and we slowly push the bike between the front seats and the frozen rider. To this day, we don’t understand how we managed to pull it off. We must have practically folded the fork and rear triangle; otherwise, we would never have been able to get that bike on board.

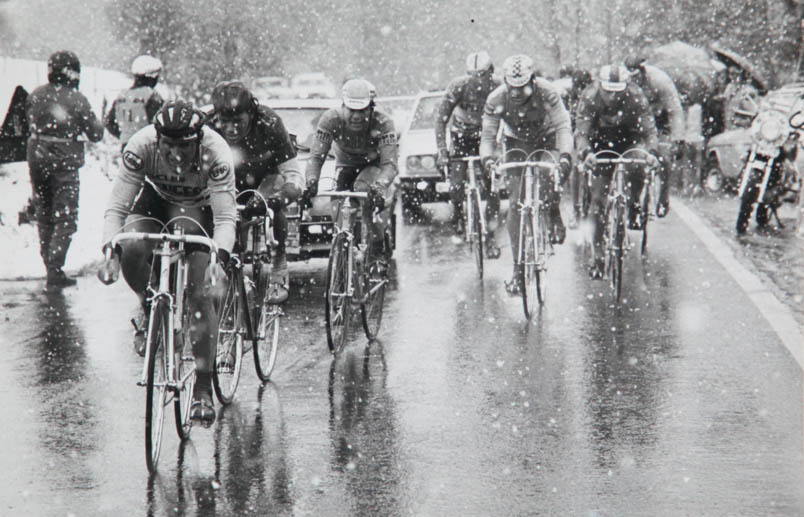

The horrors of Liège-Bastogne-Liège 1980. Hennie Kuiper bravely faces all hardships with determination. Behind Kuiper, Henk Lubberding tries to make himself as small as possible.

It has stopped snowing, but the conditions are hardly improving. Henk Lubberding comes up again in the wheel of Hennie Kuiper. Kuiper's teammate Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle rides at the front right of the group.

Hennie Kuiper leads the group behind Bernard Hinault. Henk Lubberding is glad that he can follow Kuiper's trail in the snow.

Hertekamp-gin

Our passenger is chilled to the bone. Do we have anything to drink, something that can warm him up? We rummage under our seats. This morning we received a ‘food package’ from sponsor Hertekamp. In addition to some provisions, it also contains a bottle of that genuine Hertekamp gin.

‘Here you go, Hennie, this will warm you up.’

And sure enough, ten minutes after Kuiper has consumed the contents, the chattering stops. That helps. Hennie even becomes a bit cheerful. A little later: ‘Do you happen to have another bottle?’ We dive under the front seat again. After all, each of us received such a delightful Hertekamp. Hennie’s wish is granted. Another bottle. We hear the contents clinking in the battered rider’s body. We have no trouble with Hennie until the finish line in Jambes. We have delivered him neatly to the Raleighs. No, since that fourteenth of April 1977, you don’t need to tell Hennie anything more about cold or how to effectively combat it.

Inhuman? Yes!

The weather on Sunday, April 20, 1980 is ‘too bad to even send your dog outside,’ says Ludo Peeters as the shivering riders stand at the starting line in Liège. The thermometer indicates four degrees at that moment. Icy rain drips onto the trembling riders’ bodies. ‘But at that moment, it was still possible to race,’ says Hennie. Many riders think otherwise. Many turn back immediately after the start: ‘Impossible,’ they judge. ‘This cannot be healthy.’ And indeed, it is not. The icy rain turns into wet snow. The chilling water is already seeping into the riders’ socks. The shirts and racing shorts are soaked. The temperature drops towards zero. When the snow hesitantly, but increasingly decisively, turns the landscape and trees white, this edition of the world’s oldest cycling classic takes on an apocalyptic dimension. The Italians, who have not sought shelter in a team car yet, shout ‘sciopero, sciopero’: ‘strike, strike’. But the greatly reduced peloton continues to haul themselves - chilled to the bone - up the Ardennes hills. Fingers stiffen from the cold. Some can no longer bend their fingers; they are unable to operate the brake levers in the usual way. They brake with their wrists as best as they can; operate the gear shifters, mounted on the frame in those years, with the heel of their hand up or down.

Inhuman? Yes! Madness? Yes! But the riders keep pedaling, initially following the lone escapee, Rudy Pevenage, and later braving the cold, snow, and icy rain together. Cyrille Guimard, team director of Hinault, provides his leader with a dry jersey, gloves - which he has just dried on the team car’s heater - and a balaclava. He urges him to eat. And Bernard loads up his body as much as possible. He realizes that under these conditions he needs extra fuel.

Of course Kuiper is among the survivors. At Bastogne, the turning point, more than a hundred of the 174 starters have already removed their race numbers. Hennie hasn’t. Of course not. ‘I have an iron discipline.’

But have you never thought: They can do whatever they want: I’m quitting. This is ridiculous?

No, not at all. On the contrary even. Because if the result is not quite what he had envisioned, he is angry with himself. ‘Then I wonder if I have done enough.’ He doesn’t need to ask himself that question on that twentieth of April 1980. But what about the cold then? ‘Yes, it was cold that day. But you shouldn’t talk about it at all.’ Now he sometimes looks back on that harsh battle in the Ardennes. ‘They always said: you can handle the cold well. Maybe that was true in those years, but nowadays I’m always cold when the weather is a bit less favorable. And in my case, it’s not about getting older, but it’s the fear of what I experienced that day.’ On the day itself, Hennie Kuiper only thinks about one thing: racing. Despite the cold or maybe thanks to it, he feels in his element. He must and will achieve a good result. The group approaches the Stockeu climb, traditionally one of the key moments in this Ardennes classic. The road narrows there so it’s a matter of choosing a good position before starting the climb. It means squeezing through. ‘That’s not for me,’ Kuiper knows. ‘It always causes me a lot of stress and energy.’

Nevertheless, he manages to secure a good position until he sees the road blocked by a TV motorbike. The motorcyclist waited too long to accelerate and Hennie Kuiper has to unclip a foot from his pedal toe clip. He comes to a stop. That is deadly in a climb because it means you will have difficulty getting going again. When he finally gets back on his bike, the men he’s chasing are already out of sight. That means chasing that group and losing energy, which you need so badly under these Siberian conditions. ‘I was so worked up, so angry.’

At the steepest part of the Stockeu, Hennie Kuiper loses the battle through no fault of his own. He has to get off the bike when a motor blocks his way. Ronny Claes is still on the pedals in front of Kuiper, but Kuiper is temporarily reduced to a knight on foot and loses the battle with Hinault. To the left of Kuiper, Pierre Basso struggles to keep the straight line. To the left of Basso, Fons De Wolf is on the pedals

Wetting your pants

Left and right, caregivers of the major teams do their utmost to alleviate the suffering for their riders. Ruud Bakker, caregiver of the Raleigh team, not only fills the bidons with liquid nutrition, but also mixes in cherry brandy and antigrippine. Bert Pronk has a bottle of cognac in his shirt and takes a sip from time to time to at least stay warm inside. Riders do not stop to urinate, but simply do it in their pants, as the 19th place finisher, Frits Pirard, explains. ‘Twice even. At least you get nice and warm for a moment.’ But the icy torture continues. It is more a matter of survival than racing.

While Kuiper gives it his all in the chase, there are fellow riders here and there who – overcome by the cold – run into farms to warm up behind the stove. ‘I caught up with the first group again on the Haute Levée. And there I saw that two riders had escaped: Bernard Hinault and Ludo Peeters.’ The Belgian Peeters cannot keep up with Hinault and falls back into the group. The Frenchman, sporting a red cap, is up to something big. Here is a champion at work, a rider who fits in the ranks of absolute greats like Fausto Coppi and Eddy Merckx. Initially, the group Kuiper faces some resistance, struggling to increase the gap to a minute. ‘It’s a shame I was behind when Hinault attacked. I would have liked to go with him. I’m not saying I would have beaten him, but I would have liked to challenge him. When he didn’t have such a big lead yet, I thought the Raleigh riders would close the gap. They didn’t. They couldn’t close the gap. I blame myself for waiting too long to chase.’

Against the Hinault of that April 20th, nothing can stop him. The Frenchman pedals with a determined look on his face with an incredibly large gear towards Liège. In recent weeks, he had heard and read a lot of criticism. Where was the great Bernard this spring? His 1980 record was almost blank. A meager victory in the Critérium National de la Route. That was it. Yes, there were some honorable placings in the Amstel Gold Race (5th), in Paris-Roubaix (4th), and in La Flèche Wallonne (3rd). They had made Bernard angry. In La Doyenne, he would show what cycling is all about. And he did! Eventually, he extends his lead to an impressive margin of 9.24 minutes. Kuiper climbs La Redoute, the last major climb, in the company of Flemish neo-pro Ronny Claes away from the other survivors. In the battle for second place, Hennie Claes prevails. They are among the 21 riders who ultimately reach the finish line of this 66th edition of Liège-Bastogne-Liège.

Hinault achieves one of his most impressive triumphs that day, but in light of the upcoming Tour de France, it is a Pyrrhic victory. He later realizes that he rode with too high a gear in La Doyenne. His knees are strained. In the Giro d’Italia, which he wins, there are few signs of the adverse effects of the Ardennes classic. But in the Tour de France, where the weather is extremely bad for days on end, it’s a different story. In the stage to Lille, where under the impetus of a strong Hennie Kuiper he makes a big effort, he strains his knee again. He wins this cobblestone stage ahead of Kuiper but loses the Tour. It’s game over for Hinault. That same week he has to leave the Tour which means Joop Zoetemelk has a clear path to his Tour victory. Kuiper, second in the standings, poses no threat to Joop in the Alps as he is surrounded by a strong team. Hinault still feels the effects of that heroic journey through the Belgian Ardennes on April 20th, 1980 until this day. He says he sometimes has nightmares where he is taken back to that Siberian race from back then. He has a souvenir from that icy journey: Hinault still has numb fingers to this day. When it freezes, he cannot work on the farm without gloves.

Jan Jonkers, one of the Dutch brave ones who survives the polar expedition to Liège as number sixteen, still suffers from tingling fingers over three decades later. Six Dutchmen ultimately reach the finish line on that memorable day: Hennie Kuiper (2nd), Johan van der Velde (9th), Henk Lubberding (13th), Jan Jonkers (16th), Bert Oosterbosch (17th), and Frits Pirard (19th) are the Orange heroes of one of history’s most bizarre Liège-Bastogne-Liège editions. But almost all of them have paid a price later in life for that icy adventure.

Almost ten minutes after Bernard Hinault crossed the finish line as the winner of Liège-Bastogne-Liège 1980, Hennie Kuiper wins the sprint for second place against Ronny Claes.