Milan-Sanremo 1985

The now 36-year-old Hennie Kuiper hopes to perform well in the first major classic of the season, Milan-Sanremo. It’s not really a race for Hennie, as sprinters usually take the spotlight there. But Kuiper loves this endless journey along the Italian coast, he enjoys the tifosi, the passionate Italian supporters. This is evident when he travels to Milan in 1973 in his debut year as a professional for the start of his first Primavera. ‘It was a great experience, all those people standing there, all those shops emptying out to cheer on the riders and all that applause echoing everywhere.’ Hennie doesn’t feel stressed. ‘I just thought it was fantastic. And then you hear the voice of the race director, Vincenzo Torriani. “Ancora due minuti dalla partenza.” It’s almost starting, an unprecedented atmosphere.’ There are attacks right from the start. The pace immediately exceeds 50 kilometers per hour. There are still 285 kilometers ahead. ‘When I had covered some distance, I saw a sign hanging on a tree: Sanremo still 225 kilometers away.’ That year, Kuiper wears the jersey of Ha-Ro, the development team for Rokado. Karl-Heinz Muddemann takes care of the young Dutchman. ‘Hennie today you must stay with De Vlaeminck. He will win.’ Kuiper: ‘Maybe Karl-Heinz wasn’t such a big rider, but he had it all figured out in his head.’ It is a time when team leaders can hang onto their teammates’ jerseys, saddles, and shorts for kilometers on end to save energy. Hennie watches it all with great amazement. ‘Everyone participated except Merckx and Gimondi. I stayed with De Vlaeminck until the Poggio.’ In the finale, Roger De Vlaeminck proves irresistible. Hennie finishes 58th, six seconds behind.

In the ‘85 season, Kuiper is in top form early on. Despite his advanced age, he has periods where he races like in his best years. ‘The older you get, the greater the love for the profession and for cycling becomes. You know how to train and you can easily push yourself to train harder.’

Tirreno

For Kuiper, the ‘project-Milan-Sanremo’ begins, with the stage race Tirreno-Adriatico traditionally preceding the first major Italian classic. Many teams choose this race as preparation for the classic early season because the weather in Italy is generally friendlier than in Paris-Nice, the counterpart of the Tirreno, which is held in the same period. But that turns out to be very different in 1985. When the riders rub the sleep from their eyes on Monday, March 11 to get ready for the start of the fourth stage, polar conditions prevail. Today’s stage starts from Urbisaglia, an ancient Roman village in Marche, to Porto Recanati, in the same province. The distance, 192 kilometers, is not a problem; the conditions are. The rain lashes over the backs of the riders as they head towards the start. The temperature barely rises above 0 degrees. The peloton grumbles and rushes to espresso machines in the cafes around the starting point. Damn: what is this?

Two experienced veterans calmly assess the situation. They have reached the venerable rider age of 38 and 36 years respectively: the two Dutchmen, Joop Zoetemelk and Hennie Kuiper. ‘Bad weather?’ Too bad. Cold? ‘Don’t talk about it: ride!’ Inhuman? ‘Don’t exaggerate. Race! This is part of it. This is our profession.’ Joop and Hennie are the great examples of Dutch professional cycling. They silently ride to the start of the same race, but their perspectives on starting this polar journey are vastly different. Joop races to win this Tirreno; Hennie braves the harsh conditions to be optimally prepared later that week at the start in Milan for La Primavera. He is not aiming for victory, but for training.

The brave ones who do not give up wrap themselves in every piece of clothing they can get their hands on. Joop thinks of his old profession, speed skating, and protects his body and muscles with a speed skating suit. He joins an escape with Portuguese Acacio Da Silva and American Greg LeMond, narrows down the lead after that stage to a few seconds and strikes on the penultimate day in the uphill time trial.

Zoetemelk leads, but the entire peloton suffers

Because it remains bitterly cold, even on the last day when the peloton has to tackle a tough stage of 196 kilometers around San Benedetto del Tronto. Kuiper has stayed in the race. He must and will finish that Tirreno and counts on reaping the benefits of the hardships endured in this stage race at the end of the week in Milan-Sanremo. It’s harsh and terrible. But Hennie does not give up; he goes to extremes. Totally frozen and exhausted, Hennie reaches his hotel after the race. It is still in the years when riders have to do their own laundry. ‘I arrived cold and soaking wet. Along the way, I had put on three rain jackets to protect myself from the cold and pouring rain. It was freezing in those hotels, designed for summer guests. Ceramics everywhere, nothing warm.’ Kuiper jumps into the shower. ‘I still had all my clothes and rain jackets on. The shower tap opened and I slowly peeled them off; rinsed off the first jacket, then the second, third, and finally the racing kit. I crawled straight from the shower into bed.’ Kuiper lies under the covers next day when Roger Swerts, sports director, comes into his room. ‘Sooo… Doesn’t Kuiper need to train today?’ Hennie shakes his head. ‘No, Kuiper is not training today. I’ll go outside for some fresh air later.’ He mainly stays in bed, rests and reads a bit. It is the final preparation for La Primavera.

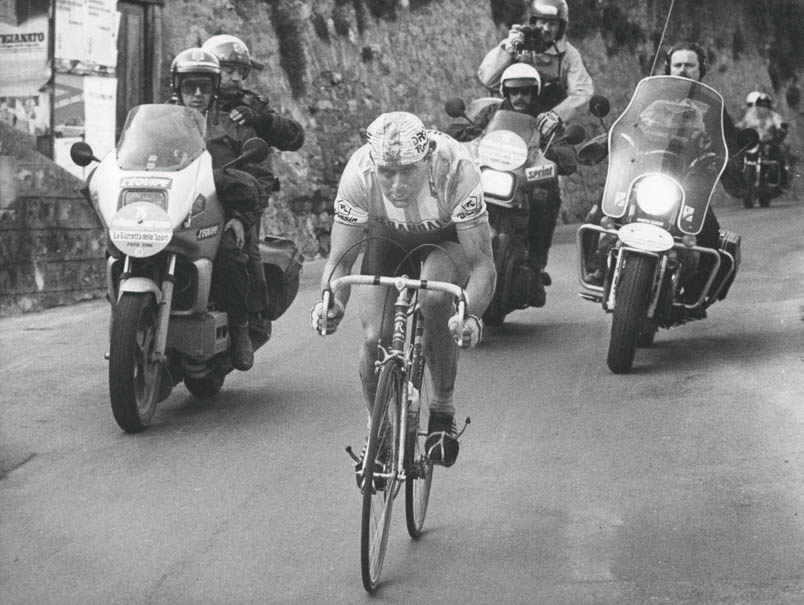

Hennie Kuiper alone on his way to victory in Milan-Sanremo

The finale of Milan-Sanremo is approaching at the Poggio. Hennie Kuiper has caught up with Teun van Vliet and Silvano Riccò (hidden behind Kuiper).

Hennie Kuiper slowly but surely distances himself from Teun van Vliet, who stays in the wheel of Silvano Riccò

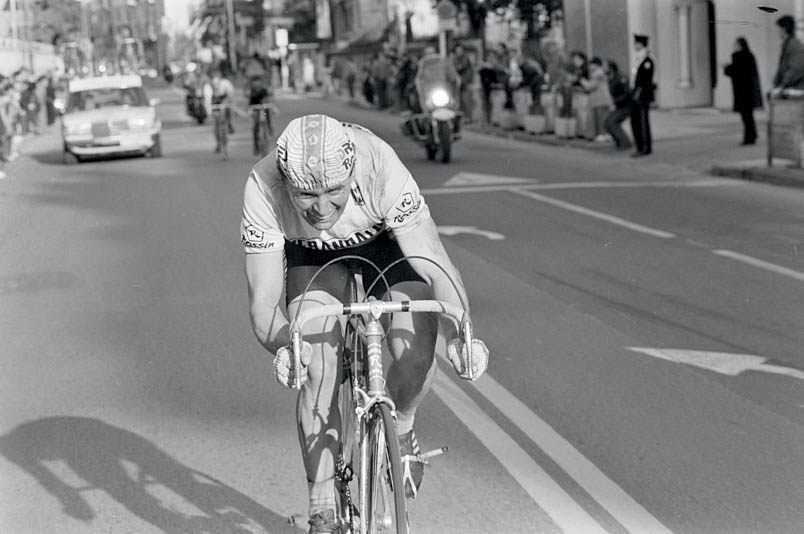

The fourth of the five Monuments is in: on the Via Roma, Hennie Kuiper wins the Primavera, Milan-Sanremo in 1985

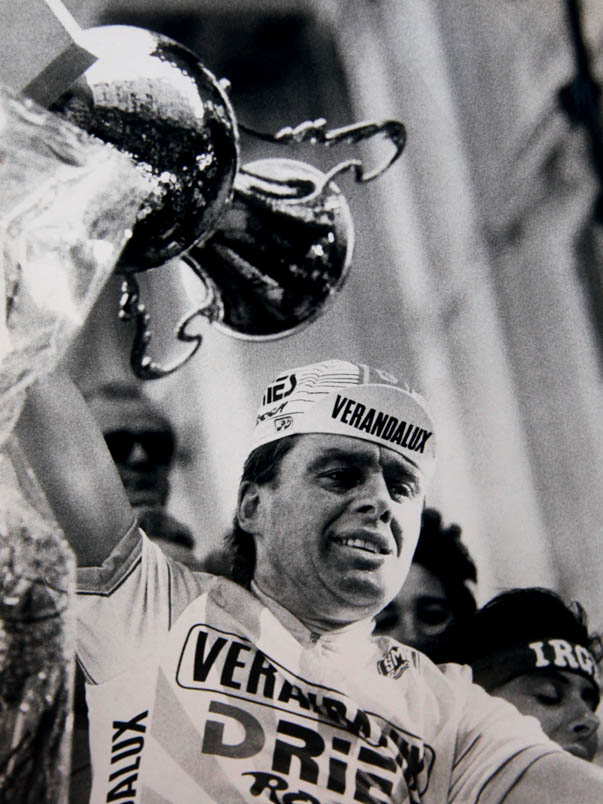

There stands a winner! Hennie Kuiper lifts the trophy of Milan-Sanremo

‘Kuiper pulled it off’

The winner of Milan-Sanremo 1985 is Hennie Kuiper. But many critics say: ‘He was not the best in that race. That was his teammate Teun van Vliet.’ The communis opinio is: ‘Kuiper pulled it off.’ Anyone who relies on the images of the finale of this Primavera is indeed inclined to think that Hennie has outsmarted his teammate Teun.

It is beyond doubt that Teun van Vliet was in top form that day. But on March 16, 1985, Hennie Kuiper also delivered a remarkable performance, as evidenced by a reconstruction of the facts. He is not a profiteer, and he did not outsmart anyone, not even in the finale of that Milan-Sanremo. It is high time to revise the image of that day.

Italy has been in the grip of severe cold for more than a week when the riders are called to the start of the Spring Classic on March 16. Many riders have barely recovered from the hardships of the ‘polar’ Tirreno, and it is bitterly cold again in Milan. Riders are bundled up tightly, wearing balaclavas, gloves, leg warmers, and thick socks. The spectators along the side shiver as race director Torriani drops the starting flag.

As the caravan crosses the Po Valley, riders see snow here and there. Only near Genoa, where the route leads along the coast, does it feel slightly warmer, although the riders have to push harder on the pedals due to strong headwinds.

At 60 kilometers from the finish, a major crash occurs. Hennie manages to stop in time. ‘But then, bam, Wladimiro Panizza crashed into me. Both wheels were bent. I needed new equipment.’

The mechanic rushes out of the car to help teammate Jan Bogaert, who also needs two wheels. Kuiper initially thinks those wheels are for him and exclaims: ‘What about me?’ The mechanic hurries back to the car, returns with two wheels, and assists Kuiper. By now, the peloton is far out of sight. Hennie is minutes behind.

Initially aided by another rider in his pursuit of the peloton, Hennie eventually has to do all the work alone. At one point, he sees a long line of team cars behind the peloton, and it is only a matter of time before he catches up again, right at the foot of Capo Berta, one of the key obstacles in this race. ‘I needed a moment to recover. Meanwhile, I saw riders from the main group dropping off left and right. So I wasn’t doing too bad.’

From Capo Berta, it is not far to Cipressa, another hill. ‘Fons De Wolf attacked there. Eric Vanderaerden was the top favorite and had all his Panasonic teammates working to catch De Wolf.’

Kuiper watches it all unfold on the slopes above him. He is not yet at the front but tries to move up and luckily gets passed by a rider from the Spanish Zor team who speeds off in pursuit of the leaders. Kuiper says: ‘I had been following Paris-Nice on television last week and saw that Zor team riding very well. When that Zor rider passed me, I immediately latched on. He took me all the way up.’

There, Hennie sees that Vanderaerden’s team has exhausted their efforts chasing De Wolf. ‘After descending Cipressa, we headed towards Poggio. There was a straight section; the front group bunched up a bit, and I thought: this won’t work. I’ll give it a try.’

The peloton, still consisting of about 40 riders at that point, is led by Panasonic’s Ludo De Keulenaer sacrificing himself for Vanderaerden. In a gentle left turn, Hennie maneuvers himself to the front on the left side of the road. Italian Silvano Riccò from small team Dromedario sees this and quickly jumps on Hennie’s wheel.

Kuiper is fortunate that De Keulenaer takes the turn quite generously. There is just enough space for Kuiper to launch his attack between a wall and De Keulenaer. Kuiper shifts into gear 12, the heaviest gear, and pushes through. Riccò responds immediately. Two riders join shortly after: Teun van Vliet and Patrick Versluys. The latter quickly falls behind. Working together harmoniously, the remaining trio heads towards Poggio, almost always a decisive point in Milan-Sanremo.

Normally, Poggio is not a climb that a professional rider should fear. The ascent is only four kilometers long with an average gradient of 3.7 percent which is not particularly challenging. However, this climb often marks the final selection because by then riders have already covered about 275 kilometers.

The joy of Hennie Kuiper is indescribable. The Italian Comedia del Arte around the winner immediately breaks out in all its intensity.

Teun van Vliet

Teun van Vliet is feeling great on this day. He is climbing the hill at an incredible pace, with the breathless Riccò on his wheel. On television, Mart Smeets says: ‘Kuiper tactically creates a gap.’ But that turns out not to be the case at all. Hennie says: ‘I just couldn’t keep up with him.’ In hindsight, this has become Van Vliet’s downfall. Because the Poggio requires a special approach. Those who expend their energy too early, like Teun van Vliet, fall short in the real finale. ‘Your legs fill up,’ Hennie knows: ‘then you can’t move forward.’

Kuiper himself is in third place. His friend De Cauwer says: ‘And that’s typical Kuiper. He doesn’t say: I can’t win anymore, I give up, no, he also wants to fight for third place.’ Hennie looks back once he reaches the top. He sees motorcycles riding in the distance. But are those motorcycles from the front or the back of the peloton? They turn out to be motorcycles ahead of the peloton. Kuiper then realizes that there is still a big gap between him and the chasers. The two leaders ride ahead of him. ‘Those guys stayed put, didn’t gain any more ground on me.’

The descent begins. Between Kuiper and the duo of Van Vliet-Riccò rides the Campagnolo support car. It is a convenient target for Hennie. He knows the descent like the back of his hand. And he is a good descender. He takes the corners aggressively. Hennie remembers it vividly, ‘I could do that because we had such a strong headwind. You kept getting slowed down.’ Kuiper’s wild ride to the foot of the Poggio ends in the wake of the leaders. He reaches a flat section of road. Accelerates on the 12 towards Van Vliet and Riccò, passes them on the left and immediately opens a gap. ‘The plan was for Teun to sit in my wheel, but that didn’t happen. When I looked back, I saw a gap between me and the other two. That’s when I thought: now I have to push through.’ Van Vliet doesn’t realize how well he is doing that day. ‘I even still had my jacket in my pocket. I didn’t want to throw it away, being thrifty as I am. I didn’t realize I had climbed so hard. It wasn’t until the top that I realized.’ Van Vliet decides to descend calmly. ‘I wanted to wait for Hennie so he could lead out the sprint for me. But when Hennie caught up, he immediately took off. I was completely surprised. I really didn’t expect that.’ Teun van Vliet cannot and should not chase after Kuiper. He cannot risk Riccò surprising the two teammates at the last moment. Hennie first, Teun second; two riders from the modest Verandalux team. Can it get any better?

Initially, both of them don’t think so. Kuiper says: ‘Teun started so well. He said: “If it turns out later that I never won a big race, then I didn’t deserve to win Milan-Sanremo today either.” Teun crossed the finish line cheering. But everything changed after he called home. “You’ve been tricked,” they told him. And then stories appeared in the media accusing me of betraying him. But that’s absolutely not true. For sixteen years, I practiced the profession of professional cyclist. And I tell anyone who will listen: for sixteen years, I never tricked anyone.’ Kuiper also feels sorry for Van Vliet. ‘From day one, I had respect for that guy. As a newcomer, he impressively won a stage in the Tour of Netherlands right away. In the team, I got to know him as an ambitious rider who wanted to work hard, always gives his all and never makes excuses when things aren’t going well.’

‘In hindsight, all this commotion has been very unpleasant for me. When you win such a big race after such intense preparation in Tirreno and after that hellish chase I had to endure after Panizza crashed into me, you expect praise and not unnuanced criticism.’ The fact remains: with this Milan-Sanremo victory, Hennie secures his fourth monument win. No Dutchman can claim that achievement. 36 years old: completing the quartet. 1985 is indeed a year for Dutch oldies. Because besides old Kuiper, even older Joop Zoetemelk (38) crowns his cycling year with victory in Tirreno and…the world championship title as well. Who dares to speak now of ‘worn-out’ riders?

The strongest in Flanders

There is another monument that he almost wins for the second time, the Tour of Flanders, in that same year 1985. That day - under harsh weather conditions - he is unquestionably the best. Hennie is fueled by the criticism after Milan-Sanremo and wants to show that the victory in Milan-Sanremo was not a fluke. Not that he still needs to prove himself, but still… On April 7th, after a slide in the mud where the left toe clip is bent from the fourth peloton to the first, helped by his teammates Gery Verlinden and Jos Jacobs. On the Koppenberg, he gets caught up in the crowd.

This also happened in the 1981 edition which he eventually won. There is no panic in Hennie. Kuiper is extremely focused on getting to the top of the Koppenberg as quickly as possible so he can start chasing the leaders.

In 1985, there are no barriers yet. People from the organization, professional photographers, and spectators stand in the ditch along the road. One overzealous spectator, a young man in a yellow jacket, tries to help stranded riders by pushing them forward. He walks between the riders from left to right on the cobblestones of the narrow path. An official tries to stop him but fails. Just as he tries to cross the road again to help another rider, he gets in Kuiper’s way, who is now walking with his bike on his shoulder towards the top. Hennie reacts angrily. He swings at the man but misses his face by a few millimeters. It’s not typical behavior for Hennie, but it shows the determination of the 36-year-old rider. The incident sparks a debate about whether the Koppenberg belongs in a race of the highest level.

Hennie then climbs on foot, starts chasing again, and quickly catches up with Vanderaerden who is also stranded. Hennie is unstoppable today. He attacks, gets caught. Attacks again and gets reeled back in. He attacks for the third time and once again his breakaway companions catch up with him. It’s frustrating. He attacks again and this time, on the Varentberg, his competitors have no response. He opens up a gap of 35, 40 seconds. Hennie powers on towards the Muur. He is in great form. Then Roger Swerts comes with his team car and says: ‘Hennie, you have to wait. It’s still a long way to go until the finish line. Two more are coming.’

Approaching are two renowned riders from Peter Post’s Panasonic team: Belgian Eric Vanderaerden and Australian Phil Anderson. ‘I rode my heart out, but I decided to wait anyway. Stupid decision. I should have kept going. On the Muur I’m leading and then I pull my foot out of the toe clip. There go my chances.’ It’s a consequence of the previously bent toe clip. Kuiper sees Vanderaerden take off. Anderson manages to catch up with Kuiper but will not pass him again. In the last kilometer, he sprints away from Kuiper. It’s a double triumph for Post’s team: 1st Vanderaerden, 2nd Anderson at 41 seconds, 3rd Kuiper at 1 minute and 1 second. After Flanders, he rides a strong Paris-Roubaix where he finishes eighth. In this race where he is constantly chasing, Kuiper overtakes all riders dropping off from the front group. His eighth place in this Paris-Roubaix, his third place in the Tour of Flanders, and his victory in Milan-Sanremo establish him as part of the defining trio of the spring classics alongside Eric Vanderaerden and to a lesser extent Phil Anderson.

Bordeaux-Paris

The focus in 1985 is mainly on the monster race Bordeaux-Paris, a race of no less than 585 kilometers, of which the last 380 kilometers are behind the derny. Already in January during a meeting of his Verandalux team, Hennie announces his intention to ride Bordeaux-Paris. There is surprise, but gradually understanding grows. As someone who can handle a marathon, that’s Kuipertje: the relentless diesel, who is indestructible. He chooses Joop Zijlaard as his pacer, the restaurateur with an unprecedented shelter. Behind his hundred kilos, you are optimally sheltered from the wind, which is of the utmost importance for the stretch from Poitiers to Paris, where the dernys act as windbreakers and pacemakers for the limited group of brave souls daring to tackle this cycling marathon.

Zijlaard already has an impressive track record in 1985. As a pacer, he has amassed national titles with various riders behind him, won European championships, and is also a multiple winner of the Criterium der Aces. Bordeaux-Paris is not unfamiliar to him. When he rides with Hennie Kuiper, he has already guided Jan Breur (1976), Tino Tabak (1977), Jan Krekels (1978), Peter Gödde (1980), Willy De Geest (1981), Cees Priem (1982), and Martin Havik (1983) to Paris. But Zijlaard has never had a winner behind his mudguard. This time, he believes, it will be different. In Hennie Kuiper, he has a potential winner. The preparation is ‘Kuiper-like’. Long hard training sessions with high intensity. It starts right after Gent-Wevelgem, when Joop Zijlaard immediately meets Hennie after this classic race and covers another 100 kilometers with him behind his 80 cc Motobécane. In addition to the ‘regular’ training sessions - where up to 300 kilometers per day are logged - Hennie also imposes an iron training regime on himself during the Four Days of Dunkirk. After the stages, Zijlaard appears on the scene to once again punish the body in endless training rides.

Kuiper and sponsor Verandalux leave nothing to chance. They enlist Herman Vanspringel as an advisor. In the Netherlands, Vanspringel is mainly known as the rider who lost the yellow jersey to Jan Janssen in the final time trial in 1968. Since then, he has built a reputation as a specialist for Bordeaux-Paris. He has outperformed all competitors in this marathon no less than seven times. Vanspringel is the ideal advisor and Hennie eagerly absorbs his knowledge. Pacer Zijlaard knows what is expected of him: to ride as consistently as possible. It is tough for a rider, but it is also far from easy for a pacer, explains Zijlaard. ‘On a derny you ride with a fixed gear. So you can never stop pedaling for almost 300 kilometers. Moreover, you can’t change your position either. Because if you do that, the rider will be in the wind and that can be deadly.’

Things are going reasonably well for the Zijlaard-Kuiper duo. They are still in a promising position when, 140 kilometers before Paris, an incident disrupts Kuiper and Zijlaard’s entire battle plan. The riders take a left turn under a viaduct. The Belgian René Martens, who has taken a small lead, chooses the left lane and narrowly avoids a number of stationary cars blocking the road. Zijlaard and Kuiper, who are behind Martens, choose the right lane. But Christian Larcher, the pacer of the Frenchman Hubert Linard, also rides in the left lane, trying to avoid some traffic islands but maneuvers so clumsily that he collides with pacer Zijlaard. The Rotterdammer falls and Kuiper tumbles over him. Within five kilometers, Hennie loses a minute. Zijlaard: ‘The riders ride with monstrously large gears behind the dernys. When you have to get going again after such a fall, your cadence is disrupted. You can’t find your rhythm anymore.’ Kuiper agrees. ‘I felt absolutely no tension in my muscles.’

Within a little over 40 kilometers, the duo loses a whopping six minutes and even drops back to ninth place in the race. The Zijlaard-Kuiper pair ultimately finishes fifth (out of 13 participants) 18.54 minutes behind the winner, René Martens. The disappointment is great. Hennie had envisioned it very differently. Afterwards, there is criticism heard about Kuiper and his team’s strategic approach. Hennie should have had a teammate with him who could neutralize Martens’, Duclos-Lassalle’s and Linard’s attacks instead of Kuiper himself. Furthermore, Hennie rode with a chainring of 55 teeth while conditions (read: little wind) were favorable for a chainring with 56 teeth. Winner Martens did ride with a chainring of 56 teeth. Finally, Kuiper was the only one in the top five who did not ride with a solid rear wheel so he did not make optimal use of aerodynamics unlike his competitors.

The moment when Hennie Kuiper loses the Tour of Flanders 1985 on the Muur van Geraardsbergen in 1985. It is clearly visible that the toe clip is not around but under his left shoe. Kuiper loses control over the pedals. Phil Anderson will benefit

Jacques Goddet, since 1963 together with Félix Lévitan the boss of the Tour de France, maintains a warm relationship with Hennie Kuiper, whom he - just like his more pedantic counterpart Lévitan does - regularly compliments and shakes hands with.

1985: Hennie Kuiper tanks fresh energy in Paris-Roubaix. He finishes eighth

Form disappeared

In the weeks separating Hennie from the Tour de France, it becomes apparent that the great form he had in the spring has completely disappeared. During the Tour, Kuiper does not rise above the level of a bystander. Every stage he struggles to make it to the finish line. In the fourteenth stage from Autrans-Méaudre to Saint-Étienne, Hennie Kuiper leaves only two riders behind him. Already after 26 kilometers on the Col de Romeyère, he is dropped like a beginner, but he does not yet consider giving up. He finishes 155th, almost half an hour after the winner, Colombian Lucho Herrera, completely exhausted. The next day he does not start anymore. ‘The battery was empty.’ Hennie Kuiper is overtrained. He did not cherish the form he had in the spring, but unnecessarily pushed himself too hard. ‘I should have taken rest, but I did the opposite.’ It becomes an emotional farewell there at Hotel Tereinus du Forez. As his Verandalux teammates bid farewell one by one to their team captain, Hennie struggles to hold back his tears. Then he says: ‘I am going home and will never come back to the Tour de France. After eleven participations, it’s enough.’

Behind the broad back of Joop Zijlaard, Hennie Kuiper is training for the monster ride Bordeaux-Paris

Hennie Kuiper seeks advice from Herman Vanspringel before starting the 585.6-kilometer derny race. Vanspringel has won Bordeaux-Paris seven times: 1970, 1974, 1975, 1977, 1978, 1980, and 1981.

Hennie Kuiper comes in as the number five of Bordeaux-Paris 1985, flanked on the left by Joop Zijlaard and on the right by Dick Verdoorn