Paris-Roubaix 1983

HENNIE’S RESULTS

| 1973 | 31st at 27:36 |

| 1974 | 42nd at 23:46 |

| 1975 | 29th at 16:28 |

| 1976 | 4th in same time |

| 1977 | 10th at 1:39 |

| 1978 | 6th at 4:26 |

| 1979 | 3rd at 0:40 |

| 1980 | 14th at 10:38 |

| 1981 | 6th in same time |

| 1982 | 15th at 2:38 |

| 1983 | 1st |

| 1984 | 9th at 6:16 |

| 1985 | 8th at 3:30 |

| 1987 | 11th at 3:12 |

Hennie Kuiper has lined up ten times for the queen of classics, Paris-Roubaix, when he presents himself for his eleventh edition on April 10, 1983. Kuiper has considered Paris-Roubaix as ‘his’ race for years. The journey through the Hell of the North contains all the ingredients for a battlefield he loves. Such a trial can only be endured by a rider with an unbelievable perseverance and an equally unbelievable willpower. The distance - usually somewhere between 255 and 265 kilometers - is long enough to eliminate the less talented riders in advance. The course, which leads over rough cobblestones for a large part - about sixty kilometers - wears out the riders. Riding Paris-Roubaix is suffering. The bouncing over the cobbles torments the joints. The wrists, the seat, and of course the legs are extremely put to the test. The weather often plays a decisive role, especially when it has rained and the mud from the muddy fields slides onto the road. Riders get clay masks from the splattering clods of earth, fall, curse, get back up, tirelessly start a chase. Always again. Over and over.

And yet… There is a category of riders who place Paris-Roubaix above any other race. Take Jan Janssen, winner of that race in 1967 - three years after Peter Post, who triumphed as the first Dutchman with a long-standing record average speed of 45.129 kilometers per hour. Janssen finished eighth in 1964 and knows why it was so terribly fast that year. ‘We had wind force 7, sometimes force 8 straight in our backs.’

‘In 1967 it was different,’ Janssen recalls. ‘The weather was bad, lots of rain, a large number of punctures and crashes. I stayed upright. It was a race of attrition. We entered the final with ten men. I won the sprint on the velodrome in Roubaix, partly thanks to the experience I gained on the winter track.’ For Jan Janssen, triumphing in Paris-Roubaix is one of the gems on his list of honors.

Hennie is a lover of the race, which he had never been able to finish victoriously until that April 10, 1983. He remembers from 1973, his first Paris-Roubaix in the jersey of the modest Ha-Ro team. ‘It was an exciting and grueling experience. Sometimes I rode alone, then I was in a group with others. I had no idea what position I was racing in, but those French people kept cheering me on. “Allez, mon petit.” I thought they were only doing that for me. Later I understood they were cheering for everyone. The weather was very bad, but I didn’t give up.’ When he reaches the velodrome almost half an hour after winner Eddy Merckx, following Luis Ocaña’s trail, the stewards are already preparing to close the gate. But Hennie doesn’t care. He is proud to have arrived in Roubaix in the footsteps of the greats. At a respectful distance, though, but still proud.

‘I rode away for God and country’

A year later, in Paris-Roubaix, he takes the initiative for a long breakaway with the Belgian Staf Van Roosbroeck. ‘Why? Because I found it beautiful. I didn’t think about winning or riding short. No, I thought it was wonderful to ride at the front for a long time in such a race. You get applause, you get encouraged. And then I get goosebumps. Are they doing that for me? I didn’t always ride to win. I did crazy things because I enjoyed it.’ In 1975, he does the same. He races through that feared Hell without a plan, without an idea behind his escape attempts. ‘I rode away for God and country. I just wanted to see how far I could go.’

In ‘76, it gets more serious, much more serious. He wears the rainbow jersey of the world champion and he feels that he is obliged by his new status to manifest himself at the front. ‘In Belgium, they still wondered if I was a worthy world champion. Well, if you really want to provoke me, say something like that.’ He is naturally very shy. ‘When I had to pick up my suitcase from the conveyor belt during a flight, I was often the last one. Later on, you often have to wait anyway. What’s the point of fighting your way to the front to get your suitcase off the belt a little earlier? But if you provoke me, I will respond with my legs. Like I did in Paris-Roubaix 1976.’ Kuiper rides attentively, in fifth position, and then sees Walter Godefroot increasing the pace. ‘I thought: the group is going to break. And indeed. We were away with five men. Godefroot got a flat tire. From that moment on, there were only four of us left: Francesco Moser, Roger De Vlaeminck, Marc Demeyer and me.’ He almost naturally finishes last of the quartet: but by then it is already clear that Kuiper is also capable of playing a leading role in the queen of classics. He shows this more often in the following editions of Paris-Roubaix. After his three years of riding ‘for God and country’, he finishes outside the top ten only twice until 1983: in 1980 and 1982.

By the way, he is back in the top ten in 1984 (9) and 1985 (8). In 1987, he just misses out: 11th place. It’s just that Kuiper can’t participate in 1986 and 1988 due to injuries. Otherwise, he would have finished in the top ten even more often. Especially in 1988, his last year as a professional, he performs well in the spring classics. After a frame break on the Paterberg in the Tour of Flanders, he receives a bike that doesn’t fit him. He forces himself and injures his seat area which prevents him from participating in Paris-Roubaix a week later.

Full of tension

In 1979, Hennie Kuiper reaches the podium of honor. He finishes third after a race that makes him realize that he must train even more spartanly if he ever wants to win Paris-Roubaix. In the final, the same quartet races as in 1976: De Vlaeminck, Moser, Demeyer, and Kuiper. First, De Vlaeminck gets a flat tire, followed by Demeyer. Moser and Kuiper leading, but then Kuiper feels a slow leak in his tire. He waits for his team manager, Maurice De Muer, to come and help him. He is so full of tension that he lifts his bike and throws it into the fields. When he is back on the bike, he is overtaken by De Vlaeminck. ‘That man rode so incredibly fast that I could only take the lead once. That’s when I realized: I will have to train much harder.’

Desire-Believe-Do. The sacred mantra plays through Hennie’s head again. The Desire to really win Paris-Roubaix is born there. The Belief that he can really do it has grown after his third place. The Doing is a matter of waiting for the ideal opportunity.

Three years later, in 1982, he is completely ready for the ‘Doing’. He has pushed his training to the limit. From the first kilometer, he feels: this could be my day. I have good legs and I feel strong. Overconfident as he is, he then makes a crucial mistake. At the supply station, Kuiper generously waves off the food bag with an air of ‘I don’t need that’. Then he loses some of his concentration and rides straight over a sharp stone: flat tire. No problem. New wheel. ‘It was so easy: I rode back to the front effortlessly. But then it was over just as quickly. I felt like someone was constantly hanging on my saddle. I got hit by hunger and ultimately finished fifteenth.’ Time for the ‘Doing’.

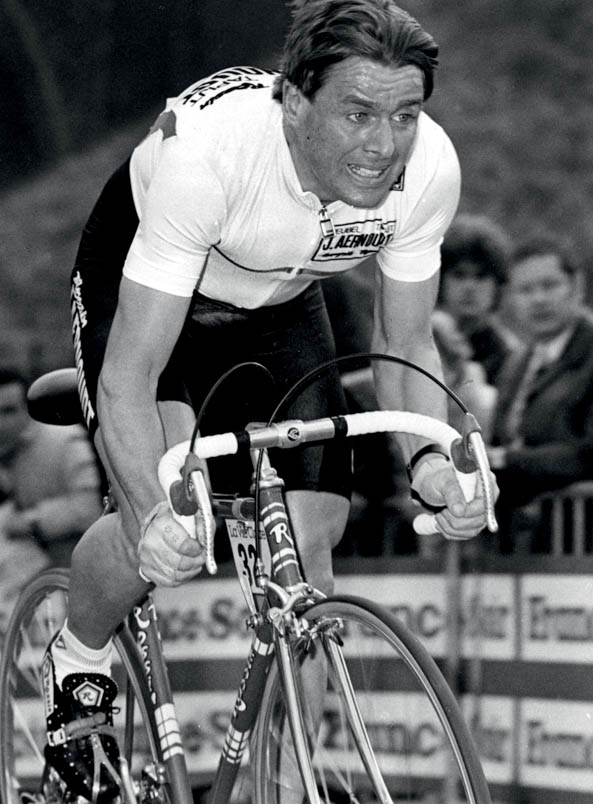

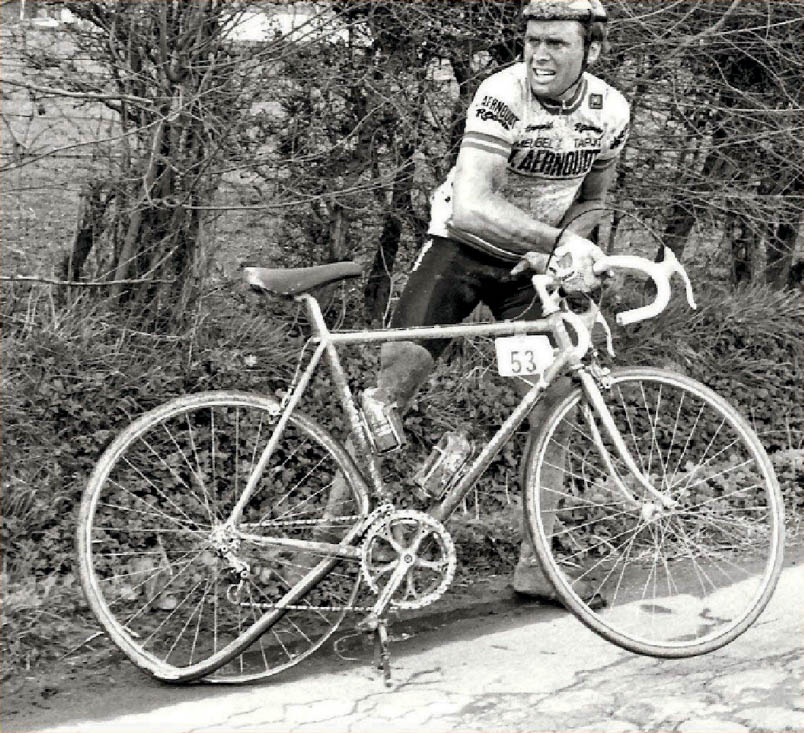

Occupational seriousness guarantees that Hennie Kuiper is already preparing himself early in the year 1983 for important goals, as seen here during the Interclubcross in Heerle (between Bergen op Zoom and Roosendaal). What he builds up in the field in terms of resistance and skillful handling will serve him excellently in Paris-Roubaix.

In 1983, Hennie Kuiper immediately shows his strength. He rides a commendable prologue in Paris-Nice and finishes tenth, 11 seconds behind the winner and teammate Eric Vanderaerden.

And they're off! Francesco Moser sets a strong pace. Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle follows. Then Hennie Kuiper. Then Marc Madiot. Then Stephen Roche. Then Alain Bondue. Then Ronan De Meyer.

<img src=”https://www.kampioenwilskracht.nl/ebook/assets/images/shared/Asset1810.jpg” alt=”Modder. Smurrie. Bagger. Derrie. Blubber. Moor. Slijk en krot en prut en drek. Het ligt er allemaal in Parijs-Roubaix 1983…

Mud. Sludge. Muck. Filth. Slime. Moor. Mud and debris and muck and dirt. It’s all there in Paris-Roubaix 1983…” class=”marginauto centerimage” />

Modder. Smurrie. Bagger. Derrie. Blubber. Moor. Slijk en krot en prut en drek. Het ligt er allemaal in Parijs-Roubaix 1983… Mud. Sludge. Muck. Filth. Slime. Moor. Mud and debris and muck and dirt. It's all there in Paris-Roubaix 1983...

Crucial turning point in the race. Francesco Moser and Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle push hard as Alain Bondue, Patrick Versluys, Ronan De Meyer, and Marc Madiot closely inspect the cobblestones behind them. Kuiper manages to avoid a fall but has to wait with one foot on the ground before he can start chasing Moser and Duclos-Lassalle.

More driven than ever

Since the first day of the year 1983, Hennie has had only one goal: Paris-Roubaix. He exhausts himself in endless training sessions. Kuiper is already not sparing with his efforts, but now he is more driven than ever. However, sponsor director Aernoudt threatens to disrupt the ultimate preparation.

This has everything to do with the semi-classic Gent-Wevelgem, which in those years serves as the midpoint between the Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix. So, the first Sunday of April the Tour of Flanders, the following Sunday Paris-Roubaix and between those two races, on Wednesday, Gent-Wevelgem, a race in which mainly sprinters come to the fore. It so happens that the gigantic furniture palace of the sponsor is located on the route of Gent-Wevelgem. It is for Jacky Aernoudt the chance to show off his professional cycling team. He expects all his stars to pass by his palace. So he orders the team management to appear at the start in Ghent with the strongest possible lineup. José De Cauwer protests. ‘Kuiper needs to perform well in Paris-Roubaix on Sunday and Gent-Wevelgem has no place in the preparation. What does he, as a non-sprinter, have to do there?’ Aernoudt persists. ‘Yet I want to see Kuiper in the team.’ And José refuses again. It goes on like this for a while, but De Cauwer sticks to his refusal. ‘Then I’ll see you in my office on Monday,’ the director replies threateningly. De Cauwer shrugs. He has won for now, now it’s up to Hennie. On the day of Gent-Wevelgem, Kuiper pushes himself in a seven-hour training session. He races through the Zeeland countryside on a big gear. The next day, he repeats that incredibly tough exercise. When he gets home, he can barely open the front door due to exhaustion. He showers, eats a meal, and collapses completely exhausted on his bed. When José calls him, he says: ‘I’m completely shattered.’ ‘Good,’ his team leader replies. ‘You will be good on Sunday. You have two days left to rest. Just crawl into bed, it will be fine.’

THE COBBLESTONES OF PARIS-ROUBAIX 1983

81st edition

Start: Compiègne

Finish: Vélodrome de Roubaix

274 km

Number of cobbled sections: 33

Total length: 53.7 kilometers

| 2900 meters | Neuvilly > Inchy |

| 200 meters | Viesly |

| 1800 meters | Viesly > Quiévy |

| 3700 meters | Quiévy |

| 1600 meters | Saint-Python |

| 1300 meters | Saulzoir > Verchain Maugré |

| 1700 meters | Verchain > Quéréniang |

| 1300 meters | Quérénaing > Artres |

| 2900 meters | Artres > Aulnoy les Valenciennes |

| 2400 meters | Arenberg Forest |

| 1700 meters | Wallers |

| 2900 meters | Erre > Wandignies Hamage |

| 2300 meters | Marchiennes > Brillon |

| 2400 meters | Tilloy > Sars-et-Rosières |

| 1100 meters | Orchies (Chemin des Prières) |

| 600 meters | Orchies (Chemin des Abattoirs) |

| 3100 meters | Auchy > Bersée |

| 3000 meters | Bersée > Mons en Pévèle |

| 200 meters | Phalempin |

| 700 meters | Phalempin |

| 1800 meters | Phalempin > Martinsart |

| 1100 meters | Martinsart |

| 400 meters | Avelin |

| 1100 meters | Avelin > Antroeuilles |

| 1400 meters | Le Pont-Thibaut > Ennevelin |

| 500 meters | Le Pont-Thibaut > Ennevelin |

| 1600 meters | Cysoing > Bourghelles |

| 800 meters | Wannehain > Camphin en Pévèle |

| 1900 meters | Ferme de Creplaine > Camphin |

| 2300 meters | Carrefour de l’Arbre |

| 1100 meters | Carrefour > Gruson |

| 400 meters | Gruson |

| 1500 meters | Chéreng > Hem |

Bos van Wallers

The weather doesn’t bode well for this Paris-Roubaix. From the cobbled sections in the Hell, reports seep through about waterlogged fields, muddy roads, and steadily falling rain. The peloton prepares for a tough day. Riders from Aernoudt team ride as a protective shield around Hennie Kuiper. He must conserve his strength as much as possible, at least until the Bos van Wallers, where traditionally the first major selection is made.

That impossible cobbled section, which indeed runs through a forest, was introduced by the former rider Jean Stablinski, a Frenchman of Polish origin. The Stablewski family - that was the original spelling of the family name - had moved from Poland to the mining region in northern France in search of a better life. The young Jean was sent into the mines at the age of 14, later discovered cycling, and then grew into a rider who became world champion in 1962, won stages in the Tour, Vuelta, and Giro, was crowned French national road champion four times, and also won the Amstel Gold Race. In short: a rider of stature.

As a rider, he had gotten to know the region around Roubaix well. Famous cobbled sections from Hell like Carrefour de l’Arbre, Cysoing, and Mons-en-Pévèle he knew from his own experience. He raced on roads that lay above the mines where he had worked himself. It’s not beautiful there, but you become a rider there.

After his career, he had a golden tip for Albert Bouvet, partly responsible at l’Équipe for designing the route. ‘Go take a look at La Drève des Boules d’Herin,’ he advised the organization of the hellish journey. The organization was immediately sold. Since 1968, the Bos van Wallers, because that’s what it’s about here, has been included in the route almost every year. La Drève des Boules d’Herin is 2.4 kilometers long and on the official course map bears the name Trouée d’Arenberg. The peloton fears this cobbled section. If you’re not in the first group when entering the forest, you can forget about it for the rest of the day. It is - especially in bad weather - an inferno of falling riders, broken frames, cursing and swearing riders, and above all a lot of suffering. For example, in 1998 Johan Museeuw broke a kneecap there and three years later the Frenchman Philippe Gaumont broke his thigh bone.

In 1983, as usual, the peloton races towards the infamous cobbled section at full speed. Kuiper’s teammate Adrie van der Poel asks if they are almost at the forest. ‘It will take a while,’ is the answer, but barely a hundred meters further, he realizes he was mistaken. A rusty level crossing gate hangs above the railway line over which coal used to be transported in earlier times. That level crossing gate is more or less the marker of the entrance to the forest. Hennie quickly moves forward, joins the first group of about twenty riders thundering over the cobbled section. Adrie is just too late and watches with regret as the first group pulls away.

Kuiper, Moser and Duclos-Lassalle: it's racing!

Hennie Kuiper alone and determined. Very determined. Very, very determined.

Recognized cobblestone specialists

Once again, the usual scene of bouncing riders, of twisted wheels and even broken frames. Sixteen riders survive the first climax of the Hell. Among them are recognized cobblestone specialists such as Francesco Moser, Marc Madiot, Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle, Stephen Roche, the local favorite Alain Bondue, Ronan De Meyer and yes, also Hennie Kuiper. ‘Men were dropping off continuously,’ Hennie knows. ‘After the Forest, it was every man for himself and that was something that suited me well. Due to my experience with cyclocross, I have always been able to ride well on cobblestones. Moser and Duclos kept sprinting to be the first to turn onto a new cobblestone section, but I let them go. I couldn’t win that sprint anyway. And I felt so strong that I thought: they won’t break away anyway.’ Then the group turns onto a muddy cobblestone section. A rider goes down, others fall over him. Bondue, Patrick Versluys, Demeyer and Madiot are the victims. Kuiper, who is riding slightly behind the group, sees it happen, manages to stop in time, puts a foot down and waits until the fallen riders have picked themselves up, turned their bikes in the right direction and set off again. Hennie: ‘I ride past and see Moser and Duclos riding away full throttle in the distance. I rode towards them at my own pace and later Ronan De Meyer and Madiot managed to catch up.’

Then it’s Hennie Kuiper’s turn to go down. On a very slippery cobblestone, he feels the bike slipping away. Madiot, who is riding behind him, manages to just avoid him. ‘I didn’t panic for a moment, picked up the bike and started a chase after the leading group, accompanied by a car from French television. The journalists were recording the gaps between the leading group and me. I was closing in fast on those first men.’ Hennie’s heart is pounding in his throat. He approaches the leading group. Everything in his enthusiastic body screams: catch up and overtake. ‘But then I told myself: calm down Hennie. Stay calm.’

Hennie Kuiper has distanced himself from the competition, but in the background mechanic Gilbert Cattoir is not yet at ease. He hangs out of the car preventively to be able to intervene. This is difficult because Kuiper's spare bike is in the middle of the roof. Cattoir wants to switch the bikes around, but team manager Fred De Bruyne reassures: 'We're almost there...'

Hennie Kuiper in his characteristic style - leaning on the bike - opens the throttle wide open in the final of Paris-Roubaix 1983

Carrefour de l’Arbre

He promised himself to wait with his attack until Carrefour de l’Arbre, that treacherous cobbled section, characterized by Bernard Hinault as tougher than the Forest of Wallers. It should not go like the year before when he forgot to eat, hit the wall, and finished in an anonymous fifteenth place. That called for revenge, revenge on himself. And the moment had now arrived. ‘This time I hadn’t reconnoitered the course. I knew what awaited me though. During the days of rest after the grueling training sessions, I watched everything again on video. I knew what I had to do.’ Hennie joins the group of four, working together harmoniously to increase the gap with potential chasers.

And then comes Carrefour de l’Arbre, the place where it must happen.

He shifts into a big gear, moves to the front, with Duclos-Lassalle on his wheel. Hennie doesn’t attack, no, he just adds a little more power each time. Slowly but irresistibly, he pulls away from his breakaway companions. Meter by meter, he gains ground. The men behind him struggle for breath. The diesel-Kuiper powers on, in a monotonous, steady pace. He rides on power and very convincingly. The cobbles are slick, but Hennie confidently chooses his path; now in the middle of the cobbled road, then on a tiny strip of asphalt separating the rough stone blocks from the waterlogged fields. He rides along the row of poplars, passes by the little café where he has to leave the cobbles again. The lead grows. Is Hennie finally on his way to victory in his favorite classic? Then, on the very last cobbled section near Hem, the road turns right. Kuiper steers to the other side onto the narrow strip of asphalt next to the cobbles. In a flash, he sees someone kneeling with a camera. He gambles that the man will jump aside, but the man is solely focused on capturing that perfect shot. There’s no choice but to ride through that puddle. He steers, feels the bike going down. There’s a hole in the road filled with water. The rear wheel thumps through it. Five, six meters ahead, the wheel locks up. In the final stretch, he comes to a stop while feeling the chasers breathing down his neck. The TV viewers – especially those in the Netherlands – let out a cry of horror. Ooooohhh… What a disaster! Hennie looks at the bike, sees that due to hitting the hole, the tire has come off the rim and is jammed somewhere between the brake and rim. He drops the bike in the ditch.

He needs a bike! A new bike!

That bike is on team manager Fred De Bruyne’s car. Three spare bikes are mounted on the roof: Eric Vanderaerden’s on pole position on the right side, Adrie van der Poel’s on the left side, and Hennie Kuiper’s in the least favorable position: in the middle. It takes longer to grab a bike from the middle than from one of the sides. So, the bike of the rider with least expectations gets placed in the middle position on the car.

Gilbert Cattoir

The Flemish Gilbert Cattoir is the mechanic on duty. In consultation with team manager Fred De Bruyne, he determined the positions of the bikes. ‘Fred and I had said: we place Kuiper’s bike in the middle. He hasn’t ridden so well this season yet. Assistant De Cauwer knew that Kuiper was so good, but we didn’t.’ The mechanic tries to change the situation during the race. ‘I said to Fred when Hennie escaped, damn, Kuiper’s bike is in an unfavorable position. Let’s switch.’ But Fred dismisses it with: ‘Forget it, we’re almost there.’

A few kilometers further, it happens. ‘There’s that man with his Kodak, damn.’

The car is not immediately on site. There are still two support cars between Kuiper and De Bruyne’s equipment car. Precious seconds are lost. Hennie impatiently looks for where the car is. Full of adrenaline, he claps his hands eagerly, an image that sticks in the memory of all cycling fans. There is no panic, but the need for quick action. Panic is present with team manager De Bruyne. Mechanic Cattoir first grabs two wheels from the roof, but then realizes that Hennie needs a bike, not wheels. De Bruyne snatches the wheels from his mechanic’s hands, runs to the bike and starts frantically pulling at the frame and the jammed tire. Fortunately, Cattoir keeps a cool head and acts quickly. ‘I took that bike from the roof among the others, and ran as fast as possible to Hennie, who saw me coming. Quickly… quickly… quickly…’ These are breathtaking seconds that give participants, spectators, and TV viewers palpitations. They want to see Hennie move forward. Damn it, faster, because here come Moser and company! Seconds feel like minutes. In reality, the whole operation from the moment Hennie rides into the ditch until he pulls himself back onto the asphalt a hundred meters further lasts exactly 49 seconds. The great hero: Gilbert Cattoir.

A RECONSTRUCTION BASED ON TV FOOTAGE

| 00 seconds | Hennie rides into the ditch |

| 05 seconds | Hennie off the bike. Sees that the tire has come off the rim |

| 07 seconds | Hennie sees it’s hopeless, drops the bike in the grass |

| 08 seconds | Hennie claps hands impatiently. Where is the support car? |

| 17 seconds | De Bruyne arrives with wheels. Pulls at rear wheel and tire |

| 27 seconds | Cattoir arrives with a new bike |

| 28 seconds | Hennie gets on the bike. Cattoir pushes him, keeps pushing while running. ‘Push, push,’ Kuiper encourages him |

| 33 seconds | Hennie and pushing Cattoir have to maneuver around a motorcyclist parked on the narrow strip of asphalt |

| 39 seconds | Cattoir keeps pushing with all his might. Hennie shifts to a heavier gear and tightens the strap of his right toe clip in one smooth motion |

| 42 seconds | Hennie leaves the cobblestone section and reaches an asphalt road. Cattoir gives one last strong push |

| 49 seconds | Hennie tightens the left toe clip strap and at that moment gets back into rhythm |

When Kuiper is back in motion, it is reported that the duo Moser-Duclos-Lassalle still has a gap of 17 seconds behind. Therefore, at the time of the incident, Kuiper must have already opened up a gap of over 1 minute with his fellow escapees. There are still six kilometers to go.

Francesco Moser remembers very little about the incident 34 years after that fateful Paris-Roubaix race. The Italian, who has since built a big name as a winemaker, prefers to talk about the three consecutive years where he emerged as a triumphant figure from the Hell of the North in grand fashion. In 1978 and 1979, he outperformed Monsieur Paris-Roubaix, Roger De Vlaeminck; in 1980 he relegated Gilbert Duclos-Lassalle to second place.

The reason for the delay in the final of Paris-Roubaix. Hennie Kuiper turns with the right turn. Looks to the left of the road for a track next to the road surface. And has to swerve for a crouching amateur photographer. His rear wheel hits a blow in an invisible deep hole, filled with water. Tire off! Kuiper throws the bike into the ditch. And claps his hands to get new equipment as quickly as possible

Moser: ‘Kuiper should not be given any space’

Moser obviously knows the rider Hennie Kuiper well. ‘In two races that I would have liked to win, he beat me: at the 1972 Olympic Games when I couldn’t catch up with him after he attacked, and at the 1975 World Championships, where every time I tried to chase him, one of his Dutch teammates would end up chasing me.’ He knows that you shouldn’t give Hennie Kuiper any space. ‘Once he’s gone, you won’t see him again. That was also the case in 1983. I didn’t know he had bad luck. No one told us that he had lost so much time, and we didn’t really have him in sight. No, he was gone, and then you knew it was very difficult to catch him.’

That becomes evident on that Sunday. Hennie is unstoppable. ‘As soon as I hit the asphalt, I shifted to the 13 and shortly after to the 12.’ That gear turns out to be big enough to reach top speed again. ‘I gave everything I had left in the battle. The last little hill, at Hém, I flew up.’

Normally, a professional rider wouldn’t think twice about such an obstacle, but after a grueling race of over 250 kilometers, it’s a whole different story—it can feel like a climb of the highest category. Hennie passes under the red flag, the signal that he has started the final kilometer. Next to him, he sees the red car of race director Félix Lévitan approaching. The small figure, wearing a leather cap, leans forward and speaks to the speeding rider: ‘Monsieur Kwiepèr. Mes félicitations. Vous êtes fantastique aujourd’hui.’

Hennie turns onto the track ramp. He sees supporters standing there. ‘When you are really good, you see everything.’ Then he reaches the cement of the Roubaix velodrome and starts jubilantly his final lap in front of the packed stands. Kuiper praises mechanic Gilbert Cattoir’s contribution to his great victory. ‘Gilbert won Paris-Roubaix for me.’ He is the man who keeps his composure at the decisive moment. Unlike the always nervous team manager De Bruyne who doesn’t unnecessarily fiddle with the defective bike. He arrives with the spare bike and pushes Kuiper with all his might on the extremely narrow strip of asphalt next to the cobblestones.

‘I could do that because I still had the condition of a cyclocross rider,’ Cattoir explains. ‘Until the previous winter, I did cyclocross races. And then you have to train hard to be able to run fast. That came in handy for me during that incident with Hennie.’ Cattoir pushes Kuiper as hard as he can for over a hundred meters. ‘Oh, I was exhausted, ran back to the car and had just gotten in when I saw the chasers, Moser and Duclos-Lassalle coming. If we had needed ten seconds more to help Hennie get going, they would have almost caught up with him. It was great that I was in such good shape.’

Cattoir’s contribution to Kuiper’s victory is indeed undeniably significant. Without his involvement, he might have stranded within sight of the finish line. However, all this does not diminish the fact that on April 10, 1983, Hennie achieved a historic performance, of which he can be proud in the first place.

In hindsight, he may be grateful to the amateur photographer who almost forced him into that near-fatal maneuver through that pit. Because that incident gave his victory a heroic dimension. Without that ‘damn’ photographer, we wouldn’t have experienced such a nerve-wracking bike change. It would still have been a magnificent triumph but without heroism.

The myth of the flat tire forever debunked. Kuiper did not have a flat tire in the final of Paris-Roubaix. The tire came off the rim

Hennie Kuiper takes his bike and tries to loosen the rear wheel, because Fred De Bruyne is coming with a new wheel.

Fred De Bruyne swings with all his might to loosen the wheel, but fails in his attempt

Gilbert Cattoir understands what is necessary under the given circumstances: a new bike. He has taken the middle bike from the roof of the team car and comes gliding - apart from the road surface - with seven-league steps.

Eternal glory for Hennie Kuiper. The victory in Paris-Roubaix 1983 will color a part of his life for the rest of his life

The victory on the Roubaix velodrome by Hennie Kuiper in 1983 is part of Dutch sports heritage. In a vote for the Sports Moment of the Century in December 1999, Kuiper's victory competed with, among others, the Olympic volleyball gold in Atlanta 1996, the Elfstedentocht victory of Reinier Paping, the Wimbledon triumph of Richard Krajicek, and the four gold medals in London 1948 by Fanny Blankers-Koen.

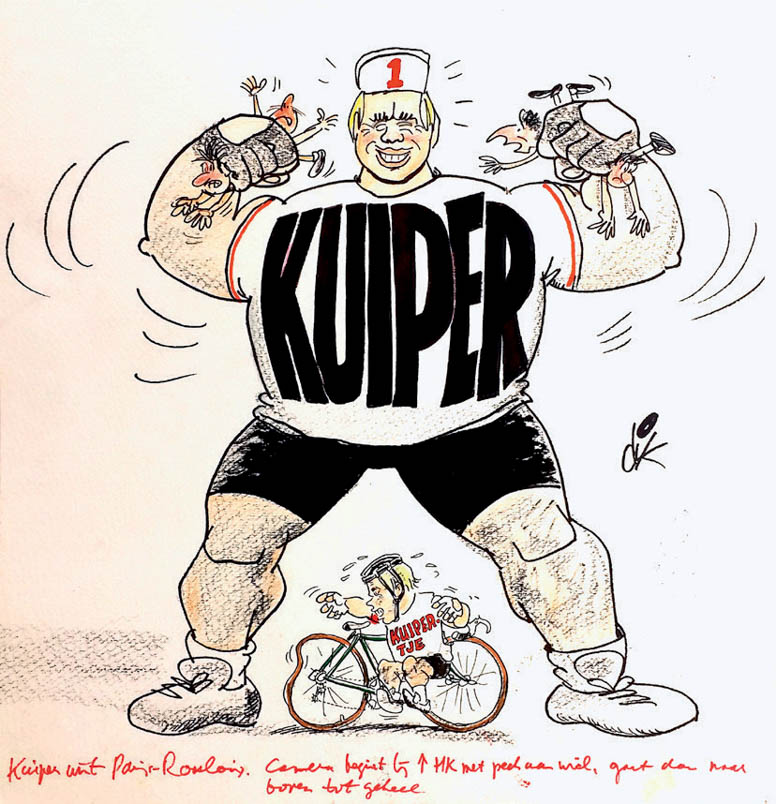

Cartoonist Dik Bruynesteyn portrays Hennie Kuiper as a real tough guy who has crushed the competition

Fred De Bruyne is quick to join in the festivities around Hennie Kuiper on the infield of the Roubaix velodrome.

Trofeo Baracchi

After his heroic victory in Paris-Roubaix, Kuiper may not have had a top season, but his results list is still impressive. In the Tour of Lombardy (4), the Vuelta (5), and in Liège-Bastogne-Liège (6), the 34-year-old shows that he still needs to be taken into account. He has to leave the Tour de France when his father passes away. His most remarkable performance is in the Trofeo Baracchi, the team time trial that he always wanted to win, but he cannot add it to his palmares in 1983 either. The first time he participates, in 1975, when he can show off his fresh rainbow jersey, he rides with Gerrie Knetemann, his future teammate at TI-Raleigh. The duo finishes third, 3.01 minutes behind the winning pair, Francesco Moser-Gianbattista Baronchelli. Freddy Maertens and Michel Pollentier finish 51 seconds ahead, also ahead of Kuiper-Knetemann.

After that, Hennie ends up in second place three times in a row. In 1978, with Joop Zoetemelk as his partner, Hennie proves to be the strongest of the duo. However, the winning pair Roy Schuiten-Knut Knudsen is 24 seconds faster at the finish line than the two Dutchmen. Four years later with the pure specialist Bert Oosterbosch, he reaches second place again at the finish line drawn near the Leaning Tower of Pisa. The pair Daniel Gisiger-Roberto Visentini turns out to be faster. Kuiper is once again second, only 24 seconds behind. He is heavily frustrated. Along the way, Oosterbosch confidently takes the lead. After all, he is the better time trialist, the specialist? But then you don’t know Hennie yet. He takes over the lead and Bertje, that brave red-haired Bertje, completely falls apart. He is glad he could keep up with Kuiper’s wheel. ‘Never again.’

Adrie van der Poel signs up for the Trofeo 1983. ‘Then I’ll ride with you,’ Van der Poel tells Kuiper. Adrie is heavily persuaded, especially by José De Cauwer. ‘Don’t do it Adrie, that Kuiper will ride you into the ground.’

Hennie doesn’t ride Adrie into the ground, but vice versa. That is to say: for 85 kilometers Van der Poel is better. Then he weakens and it becomes clear again how strong that body of that eternal diesel-Kuiper is. ‘I have never suffered so much in my life as in the last ten kilometers of that Trofeo Baracchi on Hennie’s wheel.’ Once again a duo, of which Hennie is part of as second place finisher, finishes 1.10 minutes behind the Swiss-Italian duo Daniel Gisiger-Silvano Contini. ‘It wasn’t my fault,’ Van der Poel says, but director-sportif Fred De Bruyne’s fault. ‘We were riding on those submarine bikes as usual in those days. That was supposed to be the most aerodynamic. A few minutes before the start, De Bruyne came running to tell us that he had new wheels mounted on Hennie’s and my bikes. Well, we found out about that. We had to stop twice along the way because spokes were loose. That cost us the victory.’ José De Cauwer is furious afterwards. ‘Those men should have just raced on the wheels they had trained with all week. Then nothing would have gone wrong.’

Sponsor Jacky Aernoudt’s business is doing poorly. In autumn it becomes known that the team will cease to exist. On February 28, 1984, Jacky Aernoudt’s bankruptcy is declared, but in the months leading up to it Hennie has already found another sponsor in Joop Steenbergen, director-owner of Kwantumhallen, who appears with a team under that name in the peloton. Peter Post, seeing his Raleigh team emptying out, mockingly refers to the team as the ‘pots and pans team.’ Steenbergen was watching television in April when the breathtaking Paris-Roubaix was broadcasted, from which Hennie emerged as a victor. ‘I want that too,’ Steenbergen exclaimed. He finds an ideal partner in Jan Raas, who had angrily turned his back on Peter Post. Raas contracts riders and sees Kuiper as an important pawn for the new formation. ‘I got along well with Jan. He was the man who set out the lines at Raleigh.’

The failure at Kwantum comes because Raas inexplicably appointed Lomme Driessens as team leader. Driessens was not a high flyer; he pretended to be one and had a bold talk but couldn’t build a team. When he comes to Kwantum, he is already winding down. So it doesn’t work out with Lomme. Yet in 1984 Hennie comes very close to another great Paris-Roubaix victory. A group of sixteen riders forms, including no less than five riders from Kwantum: Leo van Vliet, Hennie Kuiper, Ludo Peeters, Jacques Hanegraaf and Adje Wijnands. Such numerical superiority should lead to an unequivocal triumph. But the men do not ride for each other; there is internal competition among them. Kuiper admits guiltily: ‘Yes, I was the leader; I should have taken action but I didn’t do it; I just don’t have that trait.’ And so Irishman Sean Kelly takes home the victory.

Hennie Kuiper is not really enjoying himself at Kwantum; it bothers him terribly that there is so much rivalry between Kwantum (Raas) and Panasonic (Post) teams. When caregiver Rudy Bergmans asks him to strengthen the team of Belgian Verandalux quickly bites back yes. It is a team with Belgians Jos Jacobs and Gery Verlinden and Dutchmen Teun van Vliet, Jan and Adri van Houwelingen and later that season also Gert Jakobs among others; Roger Swerts is director-sportif - once one of Eddy Merckx’s mainstays and a good acquaintance of Kuiper.

In the Tour of 1983, Hennie Kuiper shows another strong performance, when he rides alone at the front with Bert Oosterbosch in the final of the stage to Bordeaux. In the sprint in the 'Dutch' stage town, Kuiper has to let Oosterbosch go ahead.

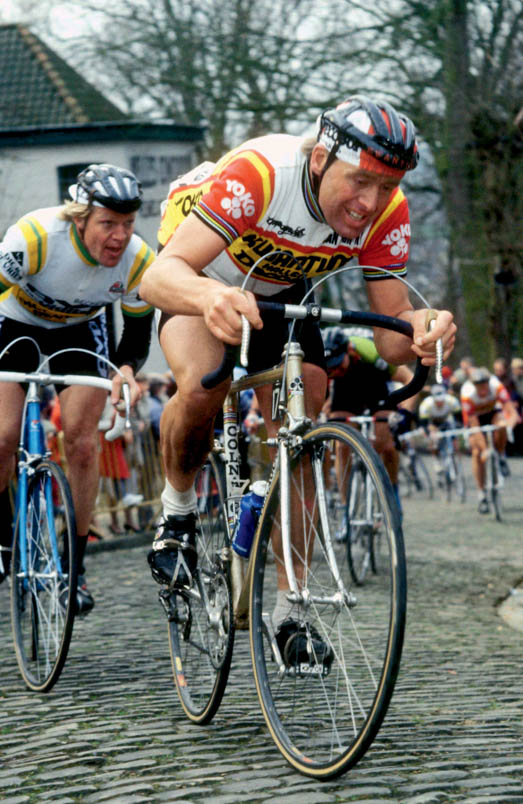

1984 in the Tour of Flanders. Parool reporter Harrie ten Asbroek (white card around the neck) has found a spot on the Koppenberg to see Hennie Kuiper coming up on foot. On the left, Alain Bondue carries the bike on his neck. Behind Hennie, Urs Freuler climbs.

Hennie Kuiper struggles up the Muur van Geraardsbergen in Flanders' Finest of 1984 with Jos Schipper following in his footsteps.

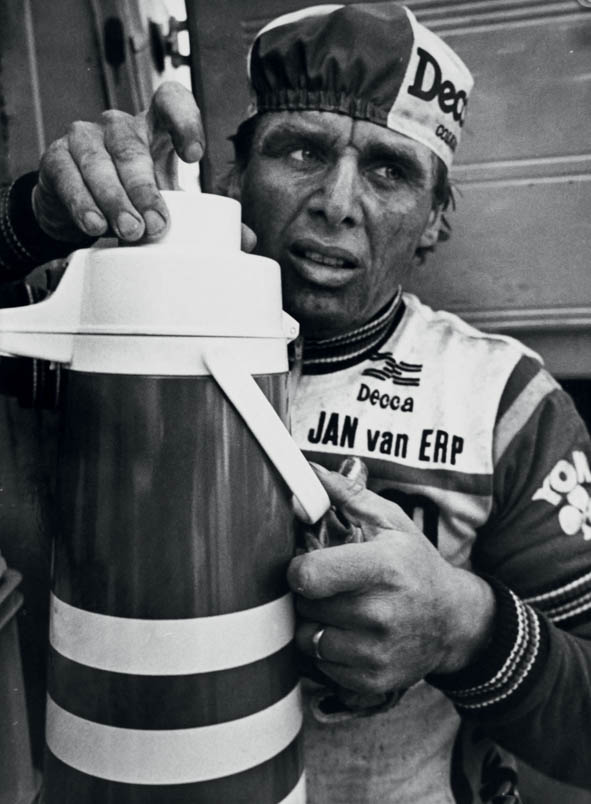

Hennie Kuiper is like few others resistant to the elements. But chilled to the bone, even Kuiper falls prey to the longing for the thermos.