A new chapter in life

When Hennie Kuiper participates in the series of races for the Coca-Cola Trophy in Germany in his final season, 1988, he is approached by Winfried Holtmann, among many other things publisher, editor-in-chief of the Sindelfinger Zeitung, entrepreneur and organizer of the Six Days of Stuttgart and Dortmund. ‘When you hand in your license as a professional cyclist, I will form a professional cycling team and you must become the sports director.’

From character-rider to sports director. It is a new chapter in the life of Hennie Kuiper

The revenge of De Cauwer, the partner of Hennie

While Hennie Kuiper embarks on his first period as a team manager, his friend José De Cauwer, who has held a team manager position since 1981, is in his second season as sports director at the ADR team. That team houses several top riders. In 1988, Dirk Demol won Paris-Roubaix for that team. Frank Hoste, Fons De Wolf, Johan Museeuw, and Eddy Planckaert form the core of the team for 1989. American Greg LeMond, former world champion and Tour de France winner, is a new addition. He was a victim of a hunting accident in early ‘87, from which he has almost fully recovered by ‘89. For the Belgian team, he is the big asset for the Tour de France.

For Peter Post’s Panasonic team, the start of the 1989 Tour is glorious. Time trial specialist Erik Breukink outperforms the competition in the prologue in Luxembourg (7.8 kilometers) and gets to wear the first yellow jersey. The second time trial, the fifth stage from Dinard to Rennes, is a serious one: 73 kilometers. Breukink, the man Post wants to succeed with, has to start immediately before LeMond. This means he has to depart two minutes before the American. De Cauwer says to Post just before the start: ‘When Greg overtakes Breukink later on, make sure to move your car aside to let me pass.’ Post laughs it off. ‘Ha, ha, ha. Erik will leave your LeMond minutes behind. I never have to let you pass.’ Post is confident in his decision. Apart from one good time trial in the Giro, LeMond has not yet shown his old form anywhere else. De Cauwer knows how good LeMond is at that moment. He has studied him closely in recent weeks. Breukink may have the reputation, but LeMond is stronger. At each intermediate checkpoint, he closes in on the rider who started before him. De Cauwer says: ‘And then I see Breukink riding far ahead of the car in the distance. I rode up to LeMond, encouraged him: ‘Overtake Breukink. Please, please. Do it for me.’

The American feels back in top form. He passes Post’s car and then flies past his pupil Breukink. While the Belgian can take his place behind his rider, Peter Post has to drop back. De Cauwer says: ‘In that Tour, we had Citroëns as support cars provided by the organization. I overtake Post, slow down when my car is next to his, and see him talking with the mechanic in the back of his car. I drove straight into the side of his car. I heard the jury say: “ADR you can pass by, you can follow behind your rider.” But before I passed Post, I gave him a strong bump.’

De Cauwer vividly remembers all the humiliations he and his friend Hennie had to endure during their time with Post’s Raleigh team. De Cauwer says: ‘How do you think you feel as a small Belgian against that big Amsterdammer with his light blue pants and spotless white shoes? How big do you feel then? It was my ultimate revenge. That’s why I say: never hurt anyone because it always comes back.’

De Cauwer’s big asset, Greg LeMond, ultimately wins that Tour after a breathtaking finale, beating the top favorite Laurent Fignon.

Stuttgart

Hennie is not aware of this. In early 1989, he ambitiously joins the project of Winfried Holtmann in Germany, which aims to promote the name of the city of Stuttgart. The city is cycling-minded, with plans to host the World Championships there. This requires publicity. What better way to achieve this than having their own cycling team? Moreover, German cycling urgently needs a team of its own. A flag bearer like Rolf Gölz is financially unfeasible for the young team in the first year. Kuiper has to make do with twelve neo-pros, ten Germans, and two Dutch riders: Ralph Moorman and Kees Hopmans. But he is full of optimism and celebrates his entry into the circles of sports directors in the early days of 1989. As a rider, Hennie is a recognized figure, but as the leader of an extremely modest team without any stars, he does not enjoy any prestige. ‘At team manager meetings, they didn’t even notice me.’

After the first season, it becomes clear: reinforcements are needed. The team is expanded to twenty riders. Hennie works tirelessly. He devotes himself day and night to the team. On the night after his birthday, February 3, he even mounts a bike rack on his car at half past one because he has to leave for a training camp in southern France the next day. No effort is too much for him. On the bike, he has always been a hard worker, and as a team manager, no less. The team now has significantly more depth than in the first year. Riders like Erwin Nijboer, Peter Arntz, Adje Wijnands, Udo Bölts, and Ludo Peeters bring experience and quality. This leads to successes but not to full recognition from the major teams and their sports directors. Even victories in the Three Days of De Panne (Erwin Nijboer) and two stages in the Vuelta (Erwin Nijboer and Bernd Gröne) do little to change that.

Telekom

At the start of the project, the plan is to develop the Stuttgart formation over a period of three years into a team ready to participate in the Tour de France. By the end of the second season, it seems that there are enough sponsors who can make that financially possible. Kuiper receives an important phone call. On the other end of the line, someone from Advertising Agency Profile from Hamburg introduces himself as a nephew of Herr Kahl, the sponsor boss, who helped Hennie get his first professional contract in 1973.

This leads to an extensive conversation with Hennie. In the end, Kuiper can proudly say, ‘I have a new sponsor. Next year I will lead a team that will bear the name Telekom on the jersey.’

Not only does his team need an extra quality boost, but the team management also needs reinforcement. It’s too much for one person. Kuiper looks in his own, Twente, environment. The choice falls on Herman Snoeijink, a teacher, also born in Denekamp, who never rode professionally but amassed an incredible 365 victories as an amateur cyclist.

The duo Kuiper-Snoeijink know each other from interval training in the early stages of their careers under the guidance of Broer Oude Keizer. Herman Snoeijink remembers how he, Hennie Kuiper, and club mate Tonny Bruns were completely exhausted after each session. For Hennie, that intensive training is an important building block for his Olympic title in ‘72 and those endless training sessions form the basis for his career as a professional cyclist; for Herman, it leads to the unprecedented winning streak in the amateur category. Snoeijink opts for a stable job in education. ‘I wanted to be in front of the class. That’s why I couldn’t ride foreign stage races. I didn’t get time off for that.’

The shared ‘suffering’ under the regime of Oude Keizer creates a bond between Kuiper and Snoeijink. It’s not surprising that the seasoned ex-professional thinks of Snoeijink two decades later when he’s looking for an assistant. In ‘91, the teacher is able to make himself available to assist Kuiper as an assistant team leader. Snoeijink: ‘Hennie asked me not only as a team leader but also because I could bring a lot in terms of training. I said ‘yes’ to his offer because I could get special leave from education. It took some effort but it worked out. That meant that if things went wrong with cycling, I could return to education.’

The teacher is faced with team leader Kuiper. As a rider - as the leader of first TI-Raleigh and later teams like Peugeot and Verandalux - he was not a leader; as a team leader either. Kuiper is neither a Guimard nor a De Muer, let alone a Post. He is serious, tries to please everyone, but above all wants to avoid trouble at all costs. Snoeijink observes him up close.

‘Hennie had one great quality as a team leader: he was very good at dealing with people and he managed to motivate riders individually tremendously. That is a characteristic that suits a team leader.’

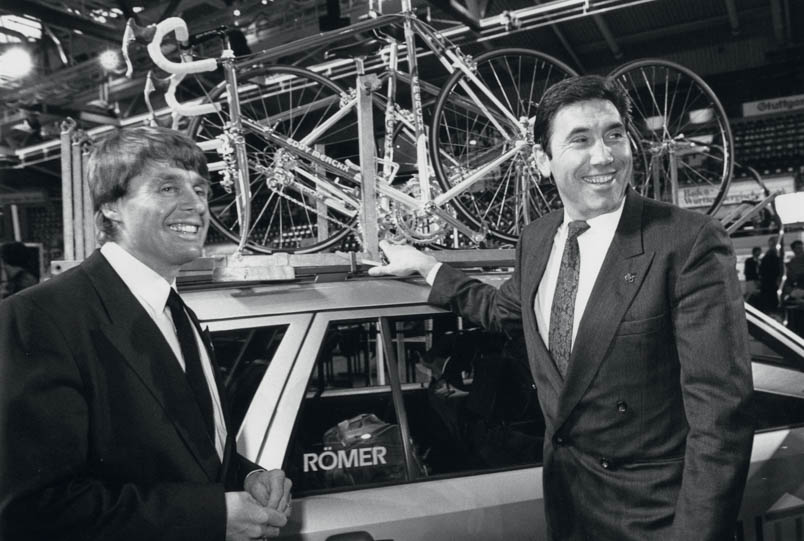

As team manager of the Stuttgart formation, the path of Hennie Kuiper crosses once again with the path of Eddy Merckx, who provides the German formation with bicycles.

Newspaper delivery boy

He sees Hennie at work and notes how big the difference is between the Kuiper from his early days and the Kuiper of today. ‘I still sometimes think back to the period when both of us, as boys of about twelve, fourteen, delivered the Twentsche Courant; me in the village of Denekamp, Hennie in the rural area. It wasn’t easy for Hennie.’ Hennie had taken over the job from his brother Frans. ‘On those roads, he learned to ride through the mud,’ says another brother, Gerard, the eldest of the Kuiper family. ‘It was only eighteen newspapers, but it was still quite a task. Because there were no paved paths to the farms. Especially in autumn and winter, you had to ride from farm to farm through the narrow cart tracks, which often turned into mud puddles. That experience would later come in handy for him in Paris-Roubaix.’

The eighteen readers who depended on Hennie for their daily news had to pay their subscription fees weekly to the delivery boy. Snoeijink, who delivered newspapers to fifty subscribers, remembers: ‘We had to hand over the money to an extremely stern-looking elderly lady with glasses. I will never forget how we went in there for the first time. I was the first one to pay. That went well, fine. Then it was Hennie’s turn. Upon seeing that strict woman, he became completely blocked. The way he spoke stutteringly at that moment was telling. But when I saw him as a team manager, followed him afterwards at lectures and in the Hennie Kuiper Museum, then I say: fantastic. I take my hat off deeply to the way he has developed.’ While all that may be true, Hennie Kuiper looks back on his early period as a team manager with mixed feelings: ‘I started that role much too early. In fact, I was still too much of a rider. If I could do it over again, I definitely wouldn’t start like that. It was too soon after my career. It would have been better if I had started as an assistant in a big team.’

No new sponsors

Nevertheless, things look very promising at the start of his third season as sports director. The name Stuttgart may have been removed from the shirts, but the logo and name of the major provider Telekom might offer good opportunities for the future. And then, suddenly, a spanner is thrown in the works. Manager Holtmann is looking for two more companies, who like Telekom recruited by Kuiper, are willing to contribute 1.2 million D-Mark each to finance the team. This is necessary as relatively expensive riders like the Swiss Urs Freuler have been signed. Gerard Veldscholten has also been recruited. However, there are no new sponsors.

The team indeed wears shirts with the name Telekom, but is financially struggling. To make matters worse, manager Holtmann, who has taken on too much, suffers a heart attack and is out of action for a considerable time. By then, the season is already in full swing. The financial situation is worrying. Despite Telekom’s sponsorship contribution (1.2 million), expenses amount to 1.6 million.

Holtmann’s wife, a financial expert at IBM, delves into the documents. She sounds the alarm and tells Telekom: ‘There are two options. Either I pull the plug on the cycling project or you take over everything, both the benefits and the burdens.’ Behind her husband’s back, Hennie Kuiper, who brought in Telekom in the first place, devises a whole new plan.

Holtmann, the manager, is ill. Telekom wants to take new directions. Kuiper is summoned to Stuttgart, where he sees Telekom executives and… Walter Godefroot, the former cyclist, sitting at the table. He immediately knows what’s going on.

The entire Holtmann structure of the Stuttgart cycling team is dismantled. Employees are laid off, including the sports technical leadership of the team: Hennie Kuiper and Herman Snoeijink. Successor Godefroot steps into a ready-made situation. ‘Not being able to continue with the project was one of the biggest disappointments in my life as a team manager.’

Hennie Kuiper in a completely different role: as an entertainer. During the presentation of special stamps on the occasion of the Grand Départ of the Tour de France in 2010 from Rotterdam, Kuiper unveils a framed stamp booklet featuring 'Dutch cycling successes'. Bernard Hinault displays the PTT Post stamps with the Grand Départ design.