Dramatic

Timmert Kuiper is increasingly making a name for himself in the world of sports, but privately things are not going well for Hennie. For a long time, the marriage with Ine seemed like a bond for eternity. However, the worlds in which the racer Hennie and the caring housewife Ine live are so completely different that it leads to a break.

As Hennie’s sports career progresses, he and Ine gradually drift further apart. It is a creeping process that cannot be reversed. He is completely taken by surprise. But when confronted with the problems, he is convinced that things will work out. In his Twents dialect, he says: ‘I thought: I’ll put my head down and I’ll manage.’ But there is nothing left to salvage. ‘It was awful,’ Hennie recalls. ‘The period during which this happened was lost time for me. You live in a trance, escape into your work. The house feels empty. There is only one word for it: dramatic.’

Ine Nolten meets him when Hennie is just a 14-year-old boy. ‘He was always very serious. I wouldn’t call him really shy. More like very modest. We liked each other from the start and that grew into a relationship.’

She accepts his complete dedication to his sport, cycling. Everything else must take a back seat. When he is abroad during his amateur days for races like the Tour of Yugoslavia, Belgium, or France, communication is limited to a postcard. The internet is still far away in the 1970s and a phone call is expensive.

How difficult it is for Hennie to show affection is evident from the text - or rather the lack thereof - on those postcards.

Ine doesn’t mind. Not then and not now either. ‘That’s just how it was in this region. You kept your feelings to yourself. Now it’s very different. You are more open towards each other and towards the children.’

For Hennie, the world is straightforward: he is a professional cyclist and does everything to make the best of it. Of course, for himself, but also explicitly for Ine and later, when two boys are born, for the family. A cycling family cannot be compared to an average family in society. It places special demands on both partners.

The house, upbringing, and family are Ine’s responsibility; Hennie ensures that it is financially possible to lead a good life. Later, yes later, there will be time to enjoy together. That doesn’t mean there is nothing enjoyable in the meantime. They have wonderful vacations. But they believe it will get even better later on.

When their first son is born in 1974, Hennie is just as happy as Ine. Sport comes into play again when choosing the name. ‘Patrick’ is the name, pronounced in a Flemish way as Patrick and not Petrick as English speakers are used to. Because the first name is borrowed from Belgian sprinter Patrick Sercu. If Hennie had hoped to draw inspiration from that name to improve his sprinting abilities, it didn’t work out. He did not become a sprinter even after Patrick’s birth.

For their second son, born five years later, they choose the first name of tennis hero Borg together. It becomes ‘Bjorn’ without dots: Bjorn. This way, the couple incorporated their love for sports into the names of their offspring.

Back to Tukkerland

After Kuipers’ career as an active rider, the family returns to their roots, to Twente. They first live for a year in their holiday bungalow in a park in Denekamp. Meanwhile, the construction of their new luxury home is nearing completion. But Ine is far from happy. She wants to take a different path. Hennie has to respect that. Ine moves out on her own.

During that period, the ‘children’ have already become advanced teenagers (Bjorn) or young men (Patrick). Bjorn initially moves in with his mother, while Patrick chooses his father’s luxurious house. The two brothers have both found their way in the world of ICT. They even started a company together during their computer science studies. Patrick has built a life in New Zealand, while Bjorn returned to the Netherlands after a few years in the United States, where he now works as an independent entrepreneur for an American company from Zeist. Hennie is proud of his sons. They have developed well and have good positions in society. They remember little of their father’s time as a rider. Patrick recalls going with his mother to fairground races in Belgium. ‘As a boy, I found Playmobil infinitely more important than what was happening around my father. I still remember getting a very large Playmobil piece from Adrie van der Poel once. I was overjoyed with it.’

He didn’t know anything about his father Hennie’s victory on l’Alpe d’Huez. It only started to come alive for him when he was eight years old and sat in front of the TV watching Hennie win an exhilarating finale at Paris-Roubaix. ‘I was very nervous. I even left the room because of the tension when he was heading towards the velodrome. And also in ‘85 at Milan-Sanremo, I was very nervous during that finale with Van Vliet and Riccò.’

Neither Patrick nor Bjorn ever saw their father’s absence as a handicap. ‘We didn’t know any different,’ says Patrick. ‘I hung out with my mother and my little brother, even though he was five years younger.’ The younger Bjorn hardly consciously experienced anything from his father’s career. He is only 9 years old when Hennie ends his career on November 6, 1988, in Oldenzaal. During Kuiper’s time as a team manager for Motorola, the sons were actively involved in his career. Patrick went twice as an assistant mechanic to the Tour of Puglia. ‘It was great fun. For me, it was like a vacation. I even wanted to cycle myself when I was twelve, but my father thought it was too early. And when I got older, I didn’t want to anymore.’

Bjorn has fond memories of working as an assistant at Motorola, which took him to races in Spain. Looking back, he understands his father Hennie’s distant attitude towards his children. ‘Intimacy was foreign to him. “Just act normal and that’s crazy enough,” was the life wisdom he had learned at home. He also carried over the attitude of my grandparents towards Hennie and his brothers and sister into his own little family.’

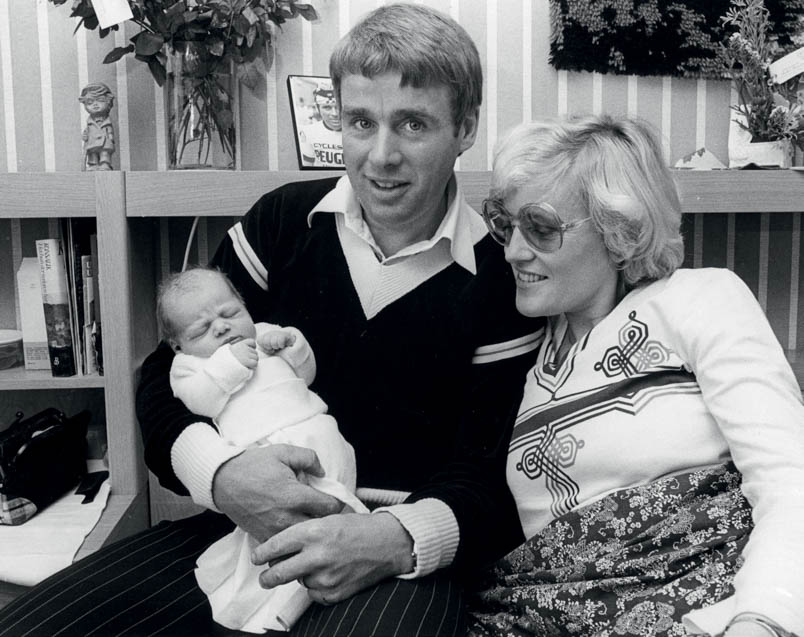

Shining with pride at the birth of son Bjorn

July 1970: Hennie Kuiper wins in Ransdaal. Ine does not leave his side. Kuiper: 'At Ketting we got three caps per year. They always went along in the wash, as you can see...'

José and Jeanne De Cauwer are involved as godfather and godmother in the family ties of the Kuiper family, when Bjorn is born

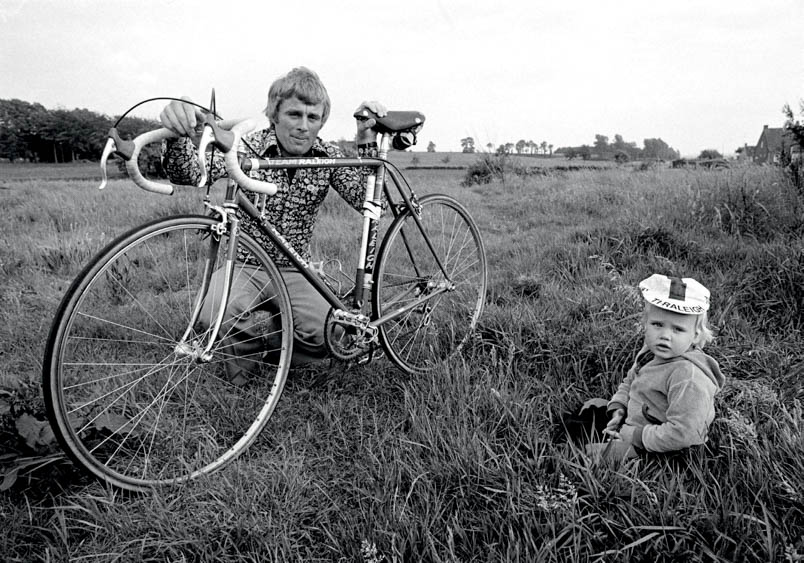

Where Hennie once started cycling among the fields in Twente, there son Patrick also tastes the cycling in a rural environment. However, Patrick does not fall for the sport, like Hennie once did.

With great precision and a deep-rooted respect for the past, Hennie Kuiper collects the relics from his own past. For his sons Bjorn (left) and Patrick, their father's history is preserved in sturdy scrapbooks and a bedroom in Hennie Kuiper's current house. In April 2017, a real Hennie Kuiper Museum was even added. Especially Bjorn shows great interest in his father's past.

Bjorn and Patrick, the children of Hennie and Ine. The youngest named after the tennis player Björn (with Umlaut) Borg and the oldest after Patrick Sercu

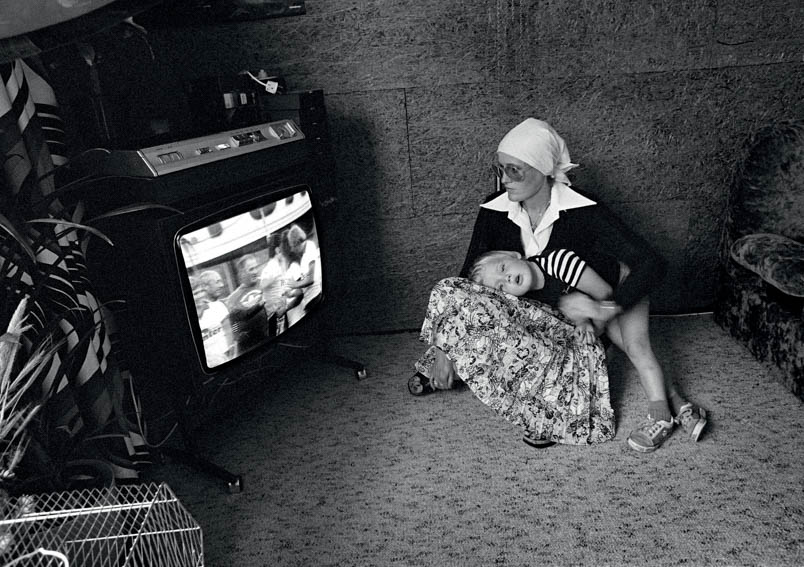

So the distribution is usually in a cycling family: the man races and brings home wages and prizes, the woman runs the household and is there for the children. During the Tour de France of 1977, Ine watches television with Patrick on her lap, before she can travel to Paris to welcome her husband on the Champs-Elysées as a hero.

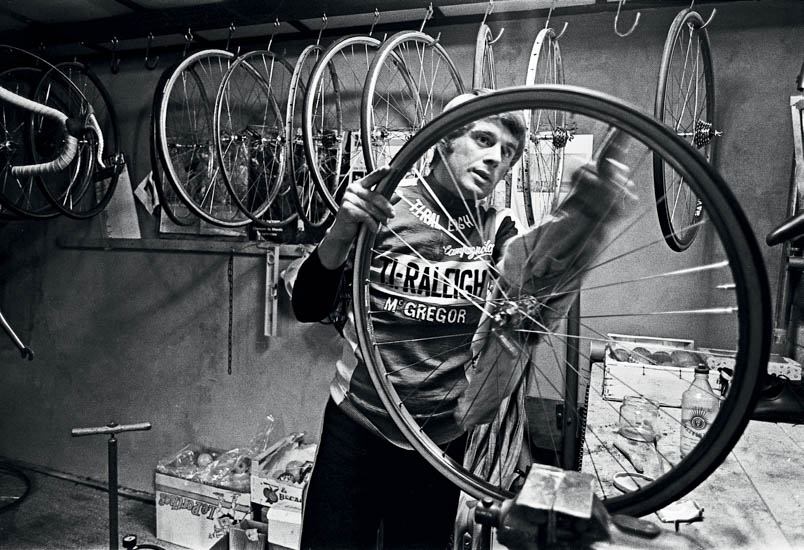

Hennie Kuiper has devoted his heart to the sport of cycling. He takes the profession very seriously. The wheels receive meticulous treatment.

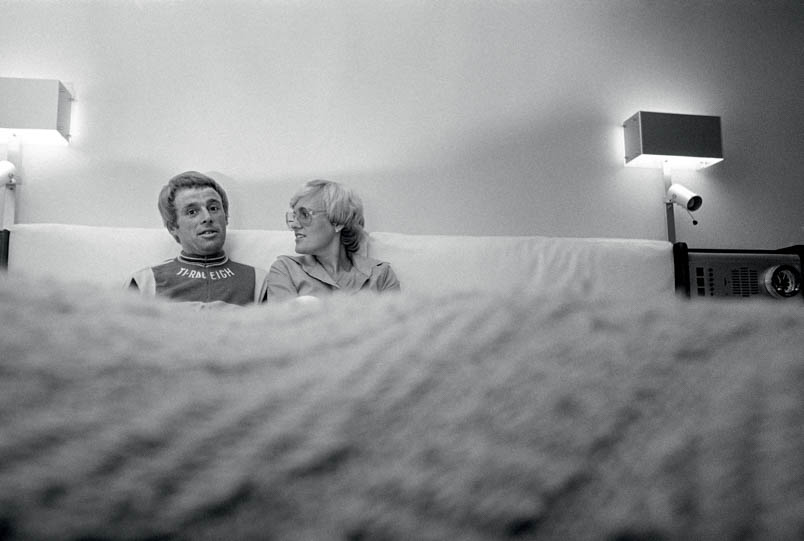

The Tour de France of 1977 is done. Hennie and Ine are resting on a bed in Paris. Although Kuiper was close to the yellow jersey and close to the overall victory, there can still be a satisfied look on his second place in the final classification.

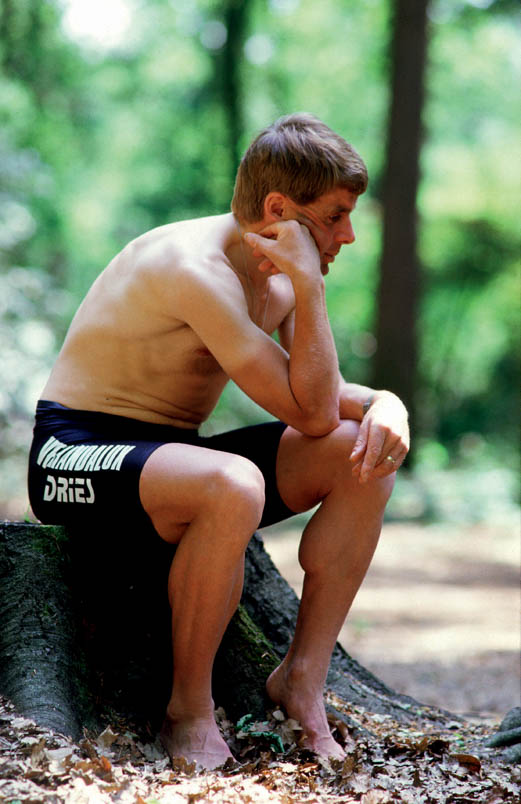

Photographer Berry Stokvis has Hennie Kuiper pose in the image of Rodin: 'Le Penseur'. Hennie Kuiper, the thinker. The man without a Verandalux shirt finds it a fitting comparison.

Hennie Kuiper goes hunting in the woods near Esbeek on November 19, 1978, in illustrious company. He immediately shoots a pheasant. Back row from left to right: football referee Leo Horn, the so-called 'Jagermeester', 'Le Fou Pédalant' Gerrit Schulte, Olympic silver clay pigeon shooter Eric Swinkels, the beater, 'My heart stood still, but my Pontiac ran' Wim van Est, and Frisol boss Nico de Vries. In front: rider Tony Houbrechts and Hennie Kuiper. Clay pigeon shooter Eric Swinkels finished second at the 1976 Montreal Olympics. He talks about shooter Kuiper: 'A few weeks ago, Hennie Kuiper came to my shop to buy a gun for hunting. I told him, come with me and let's see first if you can shoot well. He did, and I was totally amazed by the performances Hennie delivered. Out of fifty targets (clay pigeons), he hit 47 in the very first series. I told Hennie, hey, if you really start training in this sport, you can become world champion again.'